The Difficulty of Being Invisible

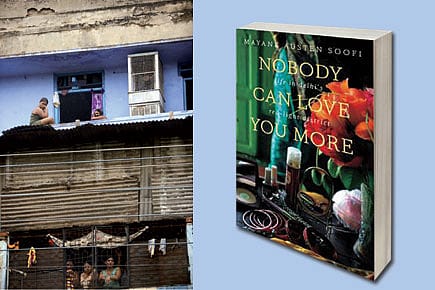

Mayank Austen Soofi has a very instrusive presence on the pages of his book on the lives of Delhi's sex workers

At one point in this book, author Mayank Austen Soofi is told, you have the pen, you have the power. But honesty is not the only virtue that can make the documentation of the ordinariness of the extraordinary lives of women in kothas—who swear in front of their children and have sex with strangers—a story that moves you. For, in his book, the author, the thin and wiry man who goes in and out of brothels and is often told by the women there that he should eat and take care of his health, becomes greater than his subjects.

After reading the book, it is this thin, wiry man that one remembers more than anyone or anything else—him playing with the children, him bonding with the women, a young sex worker holding his hand and leading him up the stairs, him dancing with Sushma to the film song Chhammak chhallo. "I'm Shah Rukh Khan, she is Kareena Kapoor," he writes on the last page. Detailing Delhi's life by unearthing the thousand stories hidden in its bylanes is not easy journalism. But it is also important to not project one- self as the hero of the story. It may be necessary sometimes to report on oneself as part of the world to give it a context. But when the author in a non-fiction book such as this appears in it so intrusively, then it betrays the extraordinary women that he has set out to portray.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Soofi's Nobody Can Love You More is a compassionate look at the daily lives of the women in the brothels on Delhi's GB Road. He becomes a part of this world, but as a reader, I would rather know more about these characters because they are the ones whose stories he set out to tell.

As writers, we all struggle to keep ourselves out of our stories. I have reported on these brothels too. And I find that it is easier to put myself in the story, recording what transpires between me and them. Then, I don't have to wait for the days and nights to pass for the moment when they would forget my presence and start living their lives, when the notebook is no strange company and I am only a fly on the wall. But to get there is a task.

One writer who has been able to master this is Katherine Boo, who always remains an invisible character in her writings. Her article for the New Yorker, 'The Marriage Cure', is a fine example of this. While reading it, you are aware that she was driving around with her character, or present at the church with them, but she keeps herself hidden from the pages. In reading her, there is then awe at her feat of observation and reconstruction.

I have often found myself struggling to be in this same invisible space when I ask my subjects to bare their souls. Daily news reporting doesn't allow one that luxury. You look for quotes and observe the locations, and you know when you have enough material for a story. But Soofi immersed himself in this world for three years; he became a part of a world that is intimidating and enchanting at the same time.

Yet, I wanted to know more about Nighat Khala's lover, the one who scribbled 'Nobody can love you more than me' on a painting on the wall of her room. She had left teen sau number kotha to visit her village. It had happened all of a sudden. He goes into the room, describes the room, the India Today magazine on the side table and asks Omar, the child, if she will come back. "I think she will," Omar said, and then the story shifts to another setting. Not all stories will solve all the mysteries, or will answer all the questions.

Soofi, who writes a popular Delhi blog and has written four alternative guide books, makes this clear when he asks himself in the book, "In these three years on GB Road, have I recorded the truth?" And goes on to say, "Maybe it is better this way. It is fulfilling enough for a writer to get a sense of GB Road without stripping bare the lives of its people." But then, the sense is lost to the reader. The fulfilment is not that transferable.

The book is both curious and tender. But the book is about Soofi. He is curious, and he is gentle. He is the man who is often asked to take care of his health, and he is the man who makes it clear that he comes from a different world, who hangs out in Jor Bagh, but goes to the underbelly because that is what attracts him, because that is where the stories are.

I envy Soofi the years spent in GB Road's kothas. As a woman, trying to get inside brothels is difficult; one is always enveloped by a sense of fear. The last time I was on GB Road, it was around 11:30 pm, and two pimps came up from behind, asking me if I wanted to see a mujra. Then they started using abusive words. I had to leave. I was with an anthropologist friend. But what if I had been alone?

But Soofi was alone there, and he spent nights there too. I wish I could be him. I read about the lives and sufferings of the women in those quarters as narrated by him, but I am left with an incomplete sense of their world. I wanted more, about them and their lives. More about them when they felt they had nothing more to hide.

There is heroism in a lot of things in life. Perhaps that is true of entering the kothas. Like when he is revolted by the greasy clothes of Sumaira and gets up to leave and Sushma tells him not to come. But he insists, "I'll come." And she says "No, you must not."

Again, the extraordinariness is transferred from the women to the narrator. Perhaps as a journalist, I see the book as a journalistic account. But who is this story about? About the author braving the pimps, and the crime, and the dangers of the red light district, or the women living there?

I don't remember much about Sushma or Mamta or Nighat or Phalak. They are the supporting cast; the protagonist is Soofi, and he plays the part well.

Only, I guess, the hero should have died, and let the others live.