Bruce Wannell: Ode to an Orientalist

‘What a world is lost when someone dies!’ wrote Bruce in September 2013, on hearing of the death of his father. He was, characteristically, on the road, in Asia. The news reached him in Istanbul, where he was on his way to see the Whirling Dervishes. ‘That day,’ he wrote, ‘we went to hear the Mevlevi sama’ which seemed to dissolve and reintegrate into a greater flow with its slow whirling white skirts and outstretched arms.’

That evening Bruce scribbled in a letter that he regretted not having put down on paper anything about his strained relationship with his father, or their partial reconciliation towards the end, and he urged me not to make the same mistake: ‘A good memoir is no conjuring against death,’ he wrote, ‘but it does save something from the ‘wreck of time.’’ And then he added, with his usual generosity and skill for fishing out just the right compliment: ‘It makes me envy all the more your art of making these past worlds live again in your writing.’

Bruce never did write his memoirs, although he tried many times. And I never managed to get him to sit down for the long series of interviews about his life, a project we had long planned, and which he, characteristically, kept putting off. During his last weeks we set a date finally to do it in early February 2020. It was another deadline he missed, and as usual it was because he had set off on a long journey. This time, though, it was one from which he will never return.

So, despite living with Bruce for probably as long as anyone has ever spent under the same roof as him, there remain many, many attics and basements of his life I have never explored and know nothing of; and there are many questions that remain unanswered. But here is what I remember.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

My life with Bruce Aziz Wannell really began on a bright summer day in Chiswick in 1999 when he came over to discuss working on some translations. I had invited Bruce to lunch; he stayed, characteristically, on and off, for twenty years.

He was a little late, I remember. He had just been to a concert, and arrived in high spirits, striding jauntily up the yard, past the roses, gravel crunching under foot. As ever, he cut a dapper and supremely elegant figure in a brightly striped blazer that looked as if it had just escaped from a Jerome K Jerome story. He was bearing, as usual, a small, rare piece of culinary exotica. Over the years we came to take for granted his albino truffles, the Algerian foie gras, the tiny tins of Iranian caviar, or the small, crisp Kurdish radishes which we were strictly instructed to eat raw, with a little sea salt. On this occasion it was, if I remember correctly, a sweet Afghan mulberry preparation, of which he was especially fond.

We had first met, briefly, five years earlier in Islamabad, in February 1994. I was there to interview Benazir Bhutto and met him at dinner one night at the house of my cousin, Anthony Fitzherbert. Anthony was then involved in an FAO project to reintroduce silk farming into Nuristan, and he travelled regularly around the Hindu Kush on foot, speaking perfect Dari and encouraging the farmers to plant mulberries rather than the opium poppy. Both men had much in common; moreover, there was a grand piano in the house next door. So twice a week Bruce used to pop over for dinner with Anthony, after an evening playing his beloved Schubert, Debussy and Chopin.

Anthony was one of the few men whom Bruce deferred to on matters Afghan: his Dari was almost as polished as that of Bruce and his travels were, if anything, even more extensive. So it was an unusually restrained and maybe even a slightly melancholic Bruce that sat opposite me that night at dinner, dressed as ever in a pristine white salvar kemise.

He was nearing the end of his eight-year stay in Pakistan, and his life there was in the process of falling apart. Recently he had had to leave Peshawar after receiving death-threats of an unspecified nature: “I am not sure of the exact reason why Bruce moved to Islamabad,” Anthony told me later, “or who it was who was threatening him. But he did feel threatened and probably genuinely so. It was a dangerous place if you upset certain people and he was not the first friend of mine to receive what are known as ‘shab nameh’ –threatening, anonymous ‘night letters’. Living as he was in a sort of ‘demi-monde’ in the old town in Peshawar the reasons could have been many. I do not think he ever told me, and I probably thought it more tactful not to ask.”

Bruce was already planning to return home, and to do so via an ambitious Arabian sea voyage through Somalia, Oman and Yemen. I was then dreaming of something similar: a journey in the footsteps of St Thomas from the Red Sea to Kerala, looking at the roots of Eastern Christianity. So we spent the evening comparing notes on dhows and Somali pirates and made vague plans to meet in the monastic library at St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai.

In the end my journey turned into something rather more firmly fixed on terra firma, a trip from Mount Athos to the Kharga oasis in the far south of Egypt, and Bruce never made it to St Catherine’s; but his odyssey homewards grew if anything even more ambitious as he trekked through the war-torn Horn of Africa to the Gulf, and then on into the heart of the Arab world. These two long journeys meant that it was five years before our paths crossed again, at a chance meeting at an oud concert in the October Gallery in London. We hugged and chatted, and I ended up asking him to come over and look at a Persian text that I thought would interest him.

During that first lunch in Chiswick, I showed Bruce a large leather-bound volume that I had just bought in the Hyderabad Chowk. It was the Kitab Tuhfat-ul-Alam by an 18th century Persian traveller, Abdul Lateef Shushtari. Bruce picked it up, opened it on a chapter describing the writer’s impressions of the 18th century East India Company in Calcutta, and began to translate from it as fluently as if he were reading the front page of The Guardian: “Neither men nor women remove pubic hair,” he read, “accounting comely to leave it in its natural state. And indeed, most European women have no body-hair, and even if it does occur, it is wine-coloured, soft and extremely fine.

By reason of women going unveiled, and the mixed education of boys and girls in one school-house, it is quite the thing to fall in love and both men and women have a passion for poetry and compose love poems. I have heard that well-born girls sometimes fall in love with low-born youths and are covered in scandal which neither threats nor punishment can control, so their fathers are obliged to drive them out of the house; she follows her whims, mingles with whom she fancies; the streets and markets are full of innumerable such once-well-bred girls sitting on the pavements.”

“Brothels are advertised with pictures of prostitutes hung at the door, the price of one night written up with the furnishings required for revelry… As a result of the number of prostitutes, atashak—a severe venereal disease causing a swelling of the scrotum and testicles—affects people of all classes. Because so many prostitutes are heaped together it spreads from one to another, healthy and infected mixed together, no one holding back—and this is the state of even the Muslims in these parts.”

Before we had even started lunch, Bruce had agreed to take the project on. By the time we had polished off his Khurasani mulberries, he had moved in. Bags, which I hadn’t even noticed, were unpacked by coffee time. There soon followed the first of the many small enhancements Bruce brought to our diet: “Willie, you don’t happen to have a small glass of grappa?” he asked. “I find a soupcon of it goes so well with mulberries.”

Soon his papers were piling up on the coffee table next door, kept in place by a pair of Mughal Mir-Farsh carpet-weights that had miraculously apparated from his luggage. The sofa bed became his place of residence for the next few months, though in truth he rarely used it as he usually worked all night, and dozed every afternoon, mouth open, head thrown back on an armchair, his snores echoing out into the kitchen.

We soon got used to Bruce’s odd working hours. He would often meet his friends for lunch ‘in town,’ then attend a late afternoon concert at the Wigmore Hall or the South Bank, a complex he said he hated but where he nonetheless spent many happy evenings. He would then stride back up the yard just as we were heading for bed, and regale us with his adventures—“Do you know Ian Bostridge? Exquisite voice. Exquisite man.” “I can never make up my mind. Which do you think is the greatest Monteverdi aria, Oblivion Soave or Lamento della Ninfa?” (In those days, prior to my musical education at Bruce’s hands, I’m pretty sure I knew neither.)

We had small children at the time, and my youngest son, Adam, was an infant of six months, just beginning to crawl around everywhere. Often, in the early morning, I would stumble blearily downstairs to get him a bottle of milk, to find that Bruce was still up, and having just finished translating some complex passage of Mughal erotica, complete with detailed footnotes of his own observations, was now standing at the Aga in a wide-sleeved kaftan, baking bread and making coffee. The kitchen smelt completely delicious.

On one occasion I had decided I was too wide awake to bother returning to bed and went out to watch the dawn break over the garden. A few minutes later, Bruce appeared with a tray. Amaretti had been crumbled on the cappuccino, while the warm, freshly baked bread had been sliced and divided in four:

“This one has Bonne Maman strawberry jam, which I do think is terribly good. This one I made from Hunza apricots sent to me by a friend from his orchards in Baltistan. And on this quarter is jasmine honey from the hives of the Sultan of Oman’s niece. Did you know Rashida? Awfully nice woman—and makes the finest honey in the Hadramut. Her bees are trained to gather pollen from the Omani night-flowering jasmine. She had an Irish nanny who taught her to sing the Rocky Road to Dublin in Arabic. Shot dead by her husband last year. So sad.” (I’m making up the details here, but it was something along these lines involving a winning combination of a name-drop of Gulf royalty, marital abuse and a tragic denouement.)

The fourth quarter of the bread was topped with a square of chocolate balancing on a great thick slab of pale, unsalted French butter.

“What’s this Brucie?”

“Black Lindt—70% Cocoa. Awfully good. My Belgian aunts would always give us the darkest of dark chocolate on baguettes every breakfast.”

From this point on, we began to discover how exotic life in suburban Chiswick could become after a Bruce makeover. Persian musicians would descend on us, and fill the garden with the sound of sitar and daff. Richard Burton’s bronze Bedouin tent turned out to be only a short walk away along the Thames in Mortlake Cemetery. We found ourselves invited to concerts in a warehouse off Brick Lane where the last of the Pontic spike fiddlers would duet with Afghan rabab players while tablas laid down the tal and Persian ghazals were sung.

Afterwards, Bruce would produce extraordinary meals of charcoal-grilled goat and great tent flaps of naan. It was then that he would introduce us to his eclectic assortment of friends: bespectacled professors of Persian, elegant French women of a certain age who needed Bruce’s help with calligraphy, Foreign Office Arabists and besuited ‘civil servants’ who were clearly spooks; musicians from Mali who played what looked like dead goats; thin, glamorous Persian emigres in Chanel and pearls, willowy art historians in velvet pants, all of them eager to meet Bruce’s latest protégé—an Afghan singer, a young Ethiopian harpist or perhaps a new Tuareg poet reciting from the Gallimard edition of his work in a blur of indigo.

Brucie was generally an unusually empathetic houseguest, but just occasionally he could get it badly wrong. Once, two very camp, stoned and bedraggled friends of Bruce rocked up uninvited by us, but clearly made welcome by Bruce, at my mother-in-law’s house. They made their appearance at noon, a full hour before Bruce was invited, solo, for a quiet family Sunday lunch of roast chicken topped by my mother-in-law’s patent, very English coagulated bread sauce. The two friends, who had apparently just emerged from a nightclub, were psychotropically wide-eyed and giggly and in other circumstances might have been entertaining company; but in the quiet of my in-laws Sunday morning they seemed quite fantastically raucous and badly behaved, especially when one of them was violently and noisily sick in the downstairs bathroom.

When Bruce swanned up in his silks, all-smiles, late, at 2pm, we had to hiss at him to remove his friends immediately before my elderly father-in-law had another coronary. Letters of grovelling apology were quickly written and what Brucie described as a “guilt cake” was despatched. But the incident was never forgotten, at least by mother-in-law, who always furrowed her eyebrows at Bruce whenever she saw him thereafter: “Isn’t that the man who brought those two dreadful…”

Amid all the lively dazzle and exotica that became part and parcel of life with Bruce, the translations continued steadily. Bruce, in fact, worked extremely hard, but as his translations were usually done alone and at night one rarely saw him at work; what was visible was the figure flouncing around in boxer shorts and a skimpy kimono at noon the following day. The translations he produced were always beautiful and occasionally quite exquisite.

As unveiled by Bruce, Shushtari’s Tuhfat ul Alam turned out to be one of the most fascinating texts of the period: a strikingly graphic account of eighteenth-century India as perceived by a fastidious and highly intelligent émigré intellectual, who reads like a sort of Persian version of VS Naipaul, avant la letter.

It had been written in 1802 when Shushtari was under house arrest in the aftermath of the scandal around which my book, White Mughals, was beginning to centre: the passionate love affair between the East India Company Resident at the Court of Hyderabad, James Achilles Kirkpatrick, with a Persian princess, Khair un-Nissa, who was Shushtari’s niece. Since the entire Shushtari clan was in disgrace, the book gave a notably jaundiced account of India, which Abdul Lateef regarded with all the hauteur that high Persian culture was capable of.

Abdul Lateef’s visit to the subcontinent started badly. On arrival, Shushtari recoiled in horror from the sights that greeted him at Masulipatnam. According to Bruce’s translation he was ‘shocked to see men and women naked apart from an exiguous cache-sex mixing in the streets and markets, as well as out in the country, like beasts or insects. I asked my host ‘What on earth is this?’ ‘Just the locals,’ he replied, ‘They’re all like that!’ ‘It was my first step in India, but already I regretted coming.’

Shushtari compared his book to ‘the flutterings of a uselessly crying bird in the dark cage of India,’ remarking that, ‘to survive in Hyderabad you need four things: plenty of gold, endless hypocrisy, boundless envy, and the ability to put up with parvenu idol-worshippers who undermine governments and overthrow old families.’ Yet for all its sectarian animosity, the Tuhfat proved to be an acerbically perceptive account, which brought the faction-ridden world of courtly Hyderabad into sharper focus than any other surviving text.

Over the months which followed, Bruce worked his way steadily and industriously through the other rare Persian-language texts about Hyderabad—the Tarikh i-Asaf Jahi, the Gulzar i-Asfiya and the Tarikh i-Yadgar i-Makhan Lal that I had brought back from the vaults of my Hyderabadi bookseller friend, Mohammad Bafna.

But it was not just translation. Bruce’s depth of knowledge of the most arcane corners of the Muslim world was unparalleled and a single Persian word could lead him to write a footnote that would make far reaching connections and bring with it a harvest of dazzling insights. About Shustari’s cousin, the ambitious Hyderabadi courtier, Mir Alam, Bruce scribbled a spidery footnote which led to this paragraph: ‘Muslim chroniclers, by contrast, singled out his qualities of ferasat, which is sometimes translated as intuition but which has far greater resonance in Persian, referring to that highly developed sensitivity to body-language that almost amounts to mind-reading, and which was regarded as an essential quality for a Muslim courtier. It is still an admired feature in much social and political life of the Muslim East.’ These were subjects about which I knew nothing, and Bruce’s deep knowledge and sometimes profound intuitions added immeasurably to the depth of the book.

I had written travelogues before, but this was my first stab at history. Bruce in many ways oversaw the whole project, editing page after page with scholarly severity, filling the margins with spiders-crawl notes, and constantly urging greater clarity and precision. He found it impossible to write narrative non-fiction himself and he eventually had to give back the advance for his own book of travels; but he was a surprisingly severe and demanding editor and guide, and with White Mughals he led me forward every step of the way. It was for this reason that in the end I decided to dedicate the entire book to Bruce.

He had transformed the entire project and it would have been a completely different book without him.

IF WHITE MUGHALS brought out Bruce at his best and most industrious, its successor, The Last Mughal highlighted some of his potential limitations as a colleague.

The book was inspired by a discovery I made in the Indian National Archives during the research for White Mughals. Rootling around the archives one morning while waiting for Hyderabadi documents to be delivered, I chanced upon a printed catalogue dating from 1921 entitled The Mutiny Papers. This was something of a surprise. It is a commonplace of books about the Great Uprising of 1857—in Britain still thought of as the Indian Mutiny but known in India as the First War of Independence—that they lament the absence of Indian sources and the corresponding need to rely on British material which carry with them not only the British version of events but also British preconceptions about the rebellion. In that sense little had changed since Vincent Smith complained in 1923 ‘that the story has been chronicled from one side only.’

Yet all this time in the National Archives there existed as detailed a documentation of the four months of the uprising in Delhi as can exist for any Indian city at any period of history— great unwieldy mountains of chits, pleas, orders, petitions, complaints, receipts, notes from spies of dubious reliability and letters from eloping lovers, the Urdu and Persian texts all neatly bound in string and boxed up.

What was even more exciting was the street-level nature of much of the material. They contained the petitions and requests of the ordinary citizens of Delhi, exactly the sort of people who usually escape the historian’s net: the bird catchers who have had their charpoys stolen by sepoys; the sweetmeat makers who refuse to take their sweets up to the trenches in Qudsia Bagh until they are paid for the last load; Hasni the dancer who uses a British attack on the Idgah to escape from the serai where she is staying with her husband and run off with her lover. Then there was Pandit Harichandra who tried to exhort the Hindus of Delhi to leave their shops and join the fight, citing examples from the Mahabharat. Or Hafiz Abdurrahman caught grilling beef kebabs during a ban on cow slaughter. Or Chandan the sister of the courtesan Manglu who rushed before the Emperor as her sister has been seized by the cavalryman, Rustam Khan.

As the scale and detail of the material available from the Mutiny Papers became apparent, and as it became obvious that most of the material had not been accessed since it was catalogued when rediscovered in Calcutta in 1921, the question that became increasingly hard to answer was why no one before had properly worked on this wonderful mass of material. Using the Mutiny Papers, and harvesting their riches for the first time, felt at times as strange and exciting, and as unlikely, as going to Paris and discovering, unused on the shelves of the Bibliotheque Nationale, the entire records of the French Revolution.

In order to properly access these vast quantities of materials, we moved the family out to Delhi in the winter of 2004, and put the children in the British School in the Diplomatic Quarter. The plan was for Bruce to come too and to work on the Persian files from the Red Fort, while Mahmood Farooqui translated those in Urdu from the sepoy camp.

In the autumn of 2004, Bruce flew out on an Ethiopian Airlines flight from Addis Ababa, where he had been walking in the mountains. The small but beautiful farmhouse we had rented had no spare bedrooms, nor a sofa bed, so I arranged for Bruce to stay with the wonderful Persian scholar and historian, Dr Yunus Jaffery, in his Mughal-era courtyard house in the Old City of Shahjahanabad. The two men were kindred spirits and Brucie loved it. He was back in his element in an old Indo-Islamic town for the first time since he was forced out of Peshawar, and he adored Dr Jaffery, who soon became his ustad. The two became firm friends and his whole family took Bruce under their wings, as they showed him the secrets of Shahjahanabad.

And then, quite quickly after his arrival, Brucie fell in love.

I was never introduced to the gentleman in question; Bruce said only that he was a dancer. But he began to turn up later and later at the archives, and when he did, he often fell asleep at his desk, had a long siesta, only to then leap up at teatime and disappear off to see his friend, and dance the night away. Trips also began to be arranged to show the dancer Brucie’s favourite places: Orchha, Mandu and a trip to Ladakh, with Simon Digby in tow.

Soon, Bruce reported that he was struggling with the scribal shorthand of the court Persian. Moreover, he said he was unfamiliar with the shikastah (literally ‘broken-writing’) script, which omits many of the diacritical marks and can be ambiguous to anyone who doesn’t have some prior idea of the contents. He also said he was unfamiliar with the surprisingly large number of Sanskrit-derived terms and other vernacular words that the Mughal Persian administrative documents contained, in contrast to the less hybrid literary Persian Bruce was familiar with.

Dr Jaffery was one of the most practiced readers of this material and Bruce could have sought his help; but he seemed to be spending less and less time with the Jafferys too. His concentration was slipping, and with it, his interest in the project.

I had flown him out and continued, ever hopeful, to pay his rent; but at the end of several months, Bruce had produced only the thinnest folder of translations, and that in large font, with lots of white space between transliterated passages of the Persian original and his somewhat emaciated renderings of them. Very few made it into the final book.

Bruce was always powered by his enthusiasms and when he was fascinated with something, nothing could restrain him. Equally, when his interest ebbed, there was very little that you could do to bring him back. The moment had passed.

IN THE WINTER of 2009, as the latest neo-colonial adventure of Tony Blair and George Bush in Afghanistan began to turn sour, I had the idea of writing a history of Britain’s first failed attempt at controlling Afghanistan in 1839. This catastrophic intervention, known in British history books as The First Afghan War, ended with the massacre of the Retreat from Kabul, from which—in legend at least—only one man from the East India Company army, Dr Brydon, made it back alive.

To anyone that knew that bit of Afghan history, newspaper headlines were beginning to look oddly familiar. The war was waged on the basis of doctored intelligence about a virtually non-existent threat. Then, after an easy conquest and the successful installation of a pro-western puppet ruler, the regime was facing increasingly widespread resistance. History was beginning to repeat itself.

In the course of my initial research I visited many of the places in Afghanistan associated with the war, and wherever I went Bruce’s name would crop up, and would open every door. In Kabul, it seemed everyone had a Bruce story and tales from his Peshawar days and his 1987 ride across Afghanistan had become legendary.

In Herat too, I found he had become an almost mythological figure. He sent me to see his old friend from Peshawar, Jolyon Leslie, who was restoring the ancient dun-coloured Herat Fort, the Qala Ikhtyaruddin. The project was for the Aga Khan, and seemed to be employing more workmen than usually toil in Cecil B deMille’s Biblical epics. When I arrived Jolyon’s army was moving vast quantities of soil and revealing the Timurid tile decoration which had lain hidden for centuries. They also made other, less welcome discoveries. During my visit, Jolyon’s team had had to remove dead Soviet cannon and anti-aircraft emplacements, as well as a massive and still live and dangerous Soviet boobytrap left as a farewell present to the Mujahedin of Herat who had besieged them. This consisted of a network of live shells connected to an old tank battery at the top of a thirteenth-century hexagonal Timurid tower.

One of Jolyon’s principal Afghan assistants had met Bruce in the middle of the Soviet Occupation, during his epic ride. He told me how Bruce had heard about some early Timurid tilework on the Soviet side of the besieged city and despite warnings, had calmly crossed the battle lines to inspect it. Wearing the Afghan dress and a Pashtun turban he affected at this period, Bruce had apparently disappeared one morning on a donkey. When he did not reappear after a week, they assumed he had been captured by the Soviets and tortured to death as a spy. But ten days later Bruce reappeared, bubbling over with excitement about some previously unknown Sufi verses he believed he had found on the tiles and been the first to transcribe.

Like everyone else, Jolyon’s foreman had said he was astonished at how flawless and idiomatic Bruce’s Dari was. So when I found a treasure trove of previously untranslated Dari sources for the 1839 war it was clear a new collaboration with Bruce was looming. It had all began when Dr Ashraf Ghani, now the Afghan President, but then the Chancellor of Kabul University, directed me to a second-hand book dealer who occupied an unpromising-looking stall at Jowy Sheer in the old city. The dealer, it turned out, had bought up many of the private libraries of Afghan noble families as they emigrated during the seventies and eighties. In less than one hour I managed to acquire eight previously unused contemporary Persian-language sources for the First Afghan war, all of them written in Afghanistan during or in the immediate aftermath of the British defeat.

The most colourful was the embittered but witty Naway Ma’arek [or Song of Battles] written by a tetchy Afghan scholar-official named Mirza Ata Muhammad. This account told the story of the war from the point of view of a dyspeptic official who started off in the service of the British puppet, Shah Shuja but later became disillusioned with his employer’s reliance on infidel support and who wrote with increasing sympathy towards the resistance.

Mirza Ata had a wittier and more immediate turn of phrase than any other writers of the period, and when I showed it to Bruce he took to the text immediately and threw himself into it. Over the next few months he had great fun bringing Mirza Ata’s often irritable prose into English as the Mirza talked proudly of an Afghanistan as being ‘so much more refined than wretched Sindh, where white bread and educated talk are unknown.’ Afghanistan, he wrote proudly, was, after all a country ‘where forty-four different types of grapes grow, and other fruits as well—apples, pomegranates, pears, rhubarb, mulberries, sweet watermelon and musk-melon, apricots, peaches, etc. And ice-water, that cannot be found in all the plains of India. The Indians know neither how to dress nor how to eat—God save me from the fire of their dal and their miserable chapatis!’

The other source I gave to Bruce to translate was perhaps the most revealing of all the Afghan accounts of the 1839 war: the Waqi’at-i-Shah Shuja, Shah Shuja’s own very colourful and sympathetic memoirs, written in exile in Ludhiana just before the war and brought up to date by one of his followers after his assassination in 1842.

Shuja explains in his introduction that, as Bruce translated it, ‘to insightful scholars it is well known that great kings have always recorded the events of their reigns, some writing themselves, with their natural gifts, but most entrusting the writing to skilled historians, so that these pearl-like compositions would remain as a memorial on the pages of passing time. Thus it occurred to this humble petitioner at the court of the Merciful God, to record the battles of his reign so that the historians of Khurasan should know the true account of these events, and thoughtful readers take heed from these examples.’

In rendering these memoirs into English, Bruce was able to translate the hopes and fears of the principal player on the Afghan side of 1839—a vital addition to the literature. Yet astonishingly, while all these sources are well known to Dari-speaking Afghan historians, not one of these accounts ever seem to have been used in any English language history of the war, and none were available in English translation until Bruce made them so.

He began working on the texts in York in early 2011 and got more and more excited the more he read. I was back in Delhi, and began to receive an almost daily flood of mails, often dotted with exclamation marks: ‘This morning I’ve been murdering Burnes in the bath—with 2 paramours!’ he wrote to me in January 2011. ‘Mirza ’Ata likes it gruesome! It all bears uncanny resemblance to modern anti-Soviet or anti-American bazaar gossip. Perhaps that’s why it was reprinted in Peshawar so recently.’

He particularly enjoyed trying to capture Shah Shuja’s personality: ‘I think it’s quite important to try and get the tone of Shah Shujas voice,’ he wrote, ‘a bit fatuous, self-idealising, stuck in the pomposity of being royal, but not unlikeable, just conceives everything in terms of abject loyalty to his person or heinous betrayal.’ He added:

‘Good luck with the writing—I wish I had been able to occupy your Delhi broom-cupboard and survive on dal-chapati, so that I could have given you my undivided attention: here in York I have NO SUPPORT SYSTEM AT ALL, and have to do everything myself.’

After what had happened with Last Mughal, I didn’t respond to the hint and after a month he nudged again. ‘I have a trapped sciatic nerve,’ he wrote, ‘as well as my index-finger sliced a full centimetre down the middle through nail and flesh while preparing pheasant for lunch— in fact a lot of minor mishaps make work quite painful and have necessitated time at the hospital A&E. I do sometimes feel the lack of anyone to help or support me during this marathon of translating… How I wish we could just sit together in your garden and talk—

I have so much enjoyed our conversations and all the unexpected sparks of intuition and enlightenment... I will not bore you with the psychotic druggies who smashed up the kitchen. Suffice to say that there was a lot of clearing up to do. BUT from tomorrow early I get back to your work and send whatever I’ve finished on Thursday—which should easily cover Ghazni, and I hope more. Quando fiam uti chelidon ut tacere desinam.

Despite the druggies who lived with him in his Council House, he seemed to be making good progress so again I left him to it. But in the autumn, when he flew out to Hong Kong to give some lectures, his spirits had clearly dipped. ‘I was feeling pretty suicidal when I left for HK,’ he wrote. ‘Life seemed to have collapsed in York, the lunatics taking over the asylum, and too much work left uncompleted. Do you still want me to finish translating for you? It seems that you’ve—quite rightly—steamed on ahead without waiting for the laggard.’

Then Hong Kong went wrong too. The Royal Geographical Society, to try and drum up some interest on Bruce’s lecture, had titled his talk in such a way as to imply that all Chinese culture actually emanated not from the Middle Kingdom but from ancient Persia: ‘Rupert whatever his name has altered the title of my RGS talk to something stupidly controversial,’ he wrote, ‘with the result that the papers and TV here are out for my blood. I’d only prepared a puff for an [Iran] guide book, not a guerre des bouffons about Chinese culture originating in Iran ... aargh!’

I finally relented and offered to email Bruce a ticket to Delhi. He more or less flew out on the next plane.

BRUCE ARRIVED in October 2011, just as the monsoon was giving way to the first chills of the Delhi winter.

We now lived on a farm on the outskirts of Delhi with a large vegetable garden. Here we had made ourselves pretty self-sufficient and kept chickens for eggs, and a family of incestuous goats for milk, and had a beehive for honey. Bruce turned down the offer of one of the children’s bedrooms and chose to live instead in a large Mughal-style tent which he had erected just outside the back door. Slowly items of furniture began to migrate from the house into the Bruce’s new Bedouin encampment: first some Baluchi carpets, then, in swift succession, a charpoy, some murrah cane chairs, an electricity lead, a radiator, various vases of flowers, a desk, and finally a bottle of malt whisky. Once his nomad’s palace was fully equipped, he threw himself into the new sources. Some days we did not see him at all except when he appeared in a skimpy bathing towel to have a shower.

Bruce was working on two remarkable heroic epic poems—the Akbarnama, or The History of Wazir Akbar Khan, by Maulana Hamid Kashmiri and the Jangnama, or History of the War, by Muhammad Kohistani Ghulami, both of which read like Afghan versions of The Song of Roland, and were written in the 1840’s to praise the leaders of the Afghan resistance. They seem to be the last survivors of what was probably once a rich seam of epic poetry dedicated to the Afghan victory, much of it passed orally from singer to singer, bard to bard: after all, to the Afghans their victory was a miraculous deliverance, their Trafalgar, Waterloo and Battle of Britain rolled into one.

Bruce loved the fact that both poems had as their villain the British Orientalist and spy, Alexander Burnes, who was usually seen as something of a hero in British accounts. In that sense they presented a mirror, which allowed us, in the words of Alexander Burnes’s cousin, Robbie Burns, ‘To see ourselves as others see us.’ For according to Bruce’s rendition of the Afghan epic poets, Burnes far from being the romantic adventurer of western accounts was instead the devilishly charming deceiver, the master of flattery and treachery, who corrupted the nobles of Kabul: ‘On the outside he seems a man, but inside he is the very devil,’ one nobleman warns Dost Mohammad:

But he of depraved nature and unholy creed

Had mixed poison into the honey

From London, he had requested much gold and silver

So that this gold may render his own schemes golden

With dark magic and deceit he dug a pit

Many a man was seized by the throat and thrown in

There remained not one amongst the Khāns of power

Whom he did not place thus on the devil’s path

When he had bound them in chains of gold

They swore allegiance to him one and all

It is, moreover, a consistent complaint in the Afghan sources that the British have no respect for women, raping and dishonouring wherever they went, and riding ‘the steed of their lust unbridled day and night.’ The British, in other words, are depicted in Bruce’s rendition of the Afghan sources as treacherous and oppressive women-abusing terrorists. This is not the way we expect Afghans to look at us.

The single known copy of the Jangnameh turned up in Parwan in 1951 lacking its front and end pages, and written on East India Company paper apparently looted from the British headquarters. The Akbarnama, which also resurfaced in 1951, this time in Peshawar, recounted the deeds of Wazir Akbar Khan, traditionally seen as the leading player in the uprising. When I showed Bruce the printed copy he picked it up and translated the introduction straight off. ‘In this book,’ he read, ‘like Rustam the Great, Akbar’s name will be remembered forever. Now this epic has reached completion, it will roam the countries of the world, and adorn the assemblies of the great. From Kabul, it will travel to every gathering, like the spring breeze from garden to garden.’

In time, due in part to Bruce’s beautiful renditions of these new Afghan voices, and partly because of the ever-more topical nature of its subject as the Taliban seized ever-more of Afghanistan, the Akbarnama’s prediction was realised: to our surprise, Bruce’s translations of the poems in Return of a King did indeed roam the countries of the world and really did come to adorn the assemblies of the great. Hilary Clinton discussed the book on an email that, thanks to Wikileaks, ended up on the front page of the New York Times. Return of a King was also read both in Obama’s White House and by President Karzai in Kabul, and I received invitations to brief both on the lessons of the history of 1839. We were also encouraged to do an Afghan launch in Kabul in the winter of 2013.

By this stage, Bruce was already back in Afghanistan, transliterating and translating Timurid gravestones for the Aga Khan. He started in his favourite old stomping grounds of Herat, where he worked on the inscriptions of the beautiful Sufi shrine, the Gaza Gah, which had been much loved by travellers as diverse as Babur and Robert Byron. Then, shortly before the launch, Bruce moved to Kabul to continue work on the gravestones there.

As usual, Bruce fell on his feet. He was living in DAFA, as the guest of the French archaeological mission, then run by the ebullient and fantastically charming beret-wearing Phillipe Marquis, who was famed in Afghanistan not just for his bravery and archaeological prowess, but also for keeping the best table, the best cheeses and the best wine cellar in the country.

Olivia, Adam and I flew in on a chilly, bright November day with high blue skies, just around the time the trees were beginning to turn. Bruce met us at the airport and later that day took us around the newly restored Bagh-i-Babur. We wandered up to the marble Shah Jahan mosque at the top of the garden, through newly-planted mulberry and apricot orchards, dotted with the last of the yellow asphodels and ragged pink hollyhocks. Adam was wide-eyed at the sight of a city which resembled one of his beloved war-movies, with its ubiquitous blast walls and gun-toting guards in APCs. But nothing impressed him quite so much as Bruce’s polylingualism, which coalition Kabul gave him ample chance to deploy.

“He spoke to us in English,” he remembered, “and to the gardeners in Dari. He translated the Mughal Persian of Babur’s tombstone about the Light Garden of the Angel King, then greeted the Turkish foreign minister, who was also touring the garden, in fluent Turkish. Finally, he took us back to DAFA where he chatted to the different archaeologists in perfect French and Italian. All in the space of about ninety minutes.” At the book launch that evening, on a freezing cold star-lit night in the open courtyard of Rory Stewart’s mud fort, within sight of the bullet-strafed ruins of the old British Embassy, Bruce was able to dust off his Arabic, Spanish and German too.

The following day we were all escorted to the great Arg, the citadel of Kabul, for our audience with Karzai. The book had had particular resonance for him as he was a direct descendant of Shah Shuja and had found himself in much the same situation as his forbear. The parallels were striking: Shah Shuja was the chief of the Popalzai tribe in the mid-19th century; Hamid Karzai was the chief of the same tribe today. Shah Shuja’s principal opponents were the Ghilzai tribe, who today make up the bulk of the Taliban’s foot soldiers.

Karzai cross-questioned us about the lessons of the book, and said that he thought the US was doing to him what the British had done to Shuja. But he would not be anyone’s puppet. “America and Britain deal with us as if we also came through a colonial experience,” he said. “We did not. We always won in the fights but lost politically. This time I want to make sure we win politically too.”

Karzai was however perhaps most animated when comparing notes with Adam about going to school in India: “I fell in love with Simla when I was at college there,” he said. “There was a lovely cinema called the Regal on the Mall by the ice-skating rink. Every Friday I would go and see Peter O’Toole movies and Goodbye Mr Chips. That is where I began to develop a lot of respect for Britain.”

We all looked at each other in surprise.

“Not forgetting what they have done to us,” he continued, “but the Raj has served India very well. I also fell in love with English literature there: I read Thomas Hardy, but my favourite is of course Shelley. I like him verrrry much. I keep reading him, regularly, regularly, once or twice a month. And I love John Betjeman: his poetry and also his talk shows on life in rural Britain. Two lovely books: Butter Toast and Trains and Tennis Whites and Tea Cakes.”

That evening Bruce threw a small party to celebrate at DAFA. Philippe opened a bottle of chilled Moet & Chandon, which we drank with gooey French brie, Afghan naan and a tin of Scottish shortbread that we had brought for Philippe.

The night ended at the foreign correspondent’s hangout, the Gandamak Lodge. There we all had dinner with the historian Nancy Dupree, who Bruce had got to know in his Peshawar days. Most of the other diners, and almost all those propping up the bar, were shaven-headed, gym-going young men in their twenties and thirties: a scrum of adrenalin-surfing hacks and cameramen who had grown up watching movies like Salvador and The Year of Living Dangerously and who now filled the bar room with their tales of derring-do in Helmand and close-shaves in Lashkar Gah.

None of them, however, had half as good a seam of war stories as the raffish silver fox sitting at the corner table in his salvar with the bird-like 86-year old woman, both of them picking quietly at their steaks. Nancy and Bruce compared notes about Masood and the Mujahedin of the eighties, and Nancy talked about her current life commuting between her homes in Kabul and Peshawar, sometimes driving herself down the Khyber Pass in her little Renault 5, sometimes by Red Cross flights: “I am their only frequent flyer,” she told us.

At this point, bursts of automatic gunfire echoed from the street outside. Immediately, all the hardened correspondents dived for cover, ourselves among them. Only Nancy continued unfazed, announcing from her seat, “I think I’ll just finish my chips.”

IN 2015, Bruce and I began what would prove to be our final project together. It was to be a history of the East India Company, and was intended to complete the Company Quartet we had collaborated on, describing the transition from the world of the Mughals to the dawn of the British Raj, between the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 and the Great Uprising of 1857.

The central figure of this project was the ill-fated Shah Alam. His life formed an arc linking the Mughal glory days when Delhi ruled all of modern India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and most of Afghanistan, to its lowest nadir during the anarchy which followed the Mughal collapse after 1739. By the end of his life, as the famous doggerel had it, Shah Alam’s rule stretched only to Palam, today the site of New Delhi airport.

At the end of 2015, we began by making a series of raids on the Persian manuscripts of the British Library. Here Bruce’s old friend Ursula Sims-Williams, and her brilliant assistant, Saqib Baburi of the Persian department, brought out trollies full of old, leather-bound Mughal manuscripts for us to look at. Some were originally from the library of the Red Fort, others from that of the East India Company Fort William College in Calcutta. Both had ended up rubbing spines and gathering dust together in the same collection under the grey skies of Kings’ Cross.

No one really seemed to have much idea what any of the manuscripts actually contained. The BL catalogue gave only the briefest description of each and almost none of them had ever been translated. Translating the 18th century Mughal Persian Bruce knew so well is a skill only a handful of scholars now possess, and the late Mughal period is one almost completely ignored by scholars. Bruce had found a Kurdish café which made excellent gozleme at the back of the BL, and we decamped there each lunchtime. As Bruce ordered Kurdish delicacies in fluent Eastern Anatolian Turkish, we tried to make up our minds which manuscripts looked most promising, and which we should have copied and set to work translating. In the end our choices came down pretty much to potluck.

This became apparent in the autumn of 2016 when Bruce moved back into the farm again to begin work on the mountain of photocopies which had just arrived from London. The first manuscript Bruce read through was the Ibrat-Nâma or Book of Admonition of Fakir Khair ud-Din. This sounded most promising, and was, he wrote in an early note, ‘full of metaphorical allusions to the political turmoil of the late 18th century, such as the tûfân-i haul-afzâ, a typhoon storm which increases a sense of terror, or the Sea of Oman which robs you of your conscious rational mind. For the admonitory purpose of this history is this: by considering these past lives, take heed for your own future.’

Sadly, the text turned out to be focused for much of its length on the reign of Akbar and Jahangir, a full century before the birth our hero, Shah Alam. This became apparent within a few days, but, as Bruce himself put it, “I am a bit like [the liner] The Queen Mary. Once I’m at full steam, it takes weeks to turn me around.” By the end of that year, Bruce’s translation notes were full of gems such as the following:

‘(8 recto) The 4th regnal year, anecdote of a qalandar visiting the court of Shah Jahan with a large tame lion called La’l Khan, who seizes a naked Yogi and mates with him as with a lioness, leaving him prostrate after an effusive ejaculation, but with no scratch or bite marks.’

It was all fabulous stuff, but of absolutely no use to The Anarchy.

So when Bruce returned the following autumn in October 2017, I did my best to keep the liner more closely on course. With this in mind, the week of Bruce’s arrival, I persuaded him to head off to the small Rajasthani town of Tonk. Here, the former Nawab’s library was said to contain a previously unstudied and untranslated full-length biography of Shah Alam by Munshi Mohan Lal. There was, however, a good reason why no one had ever studied the manuscript: the library’s rules were incredibly strict and forbad the use of laptops, photocopies or cameras. Bruce duly went there, drank endless cups of tea with the librarian, helped him with his English correspondence, attended his family wedding, exercised his charm to the full, and before long had been allowed, against all the rules, discreetly to photograph the whole manuscript on his phone.

Shortly afterwards, on a trip to Pondicherry, Bruce befriended the scholar Jean Deloche of the Ecole Francais D’Extreme Orient. He returned from the south bearing copies of a number of 18th century French travel accounts of India—Madec, Gentil and Law—but the real find was Deloche’s long out-of-print critical edition of the Voyage en Inde du Comte de Modave, 1773-1776. Modave, it transpired, was an urbane friend and neighbour of Voltaire from Grenoble who had cast a uniquely sophisticated and sardonic eye on the 18th century Indian scene, from the boulevards of Company Calcutta to the ruins of Shah Alam’s decaying Shahjahanabad. Moreover, not a word of his book had ever before been translated into English. Bruce knew immediately that he was on to a winner, and emailed a sample passage to me from Pondi:

‘The Empire held together while Aurangzeb reigned, and even for some years after he died in the early years of this century. For generally beneficial laws have a certain inner strength which allows them, for a time, to resist the assaults of Anarchy. But at last, about forty years ago, a horrible chaos overtook the Mughal empire: any spark of good that Aurangzeb had done to promote commerce was snuffed out. Ruthlessly ambitious Europeans were no less deadly in these parts. As if Europe and America were too small a theatre of war for them to devour each other, pursuing chimeras of self-interest, undertaking violent and unjust resolutions, they insisted on Asia too as the stage on which to act out their restless injustices.’

Bruce’s beautifully elegant renditions of Modave, Gentil, Khair ud-Din, Shakir Khan, Munna Lal, and the anonymous Tarikh-i-Ahmad Shahi are, I think, some of the very best work he ever did. Indeed, his last three Delhi winters, 2017, 2018 and 2019, were probably his most productive.

As well as his own work, he kept a sharply critical eye on mine and never allowed me to get sloppy. On one occasion, I sent off an article on Qajar Persian painting to a magazine which he believed to be inaccurate. He took it upon himself to ring up the editor, without telling me, and make various corrections before it went to press. Perhaps precisely because it was so easy to dismiss Bruce’s scholarship as that of a showy peacock or some willowy dilettante, he was especially rigorous about double-checking every small detail. His translations always contained the exact Persian transliterations of every sentence translated in case the accuracy of his work was ever challenged. Sometimes whole weeks, even months were lost cross-checking obscure points of Mughal court protocol or regalia: who exactly was eligible to carry the Fish Standard, the mahi maratib? Which Nawabs were eligible for alams? “Willie, a word in your ear,” he would say. “Please make sure to double check the details of the battle standard of the third Nawab of Murshidabad. I know you laugh, but these things are very important.”

Equally, he could also be scathing about those who did not meet his own high standards. ‘Wanting to massacre Professor X,’ he texted me one afternoon. ‘He is incapable of giving a correct page reference, so finding the original for his dodgy translation is like wading through a bog! He just doesn’t know Persian, at least not in any idiomatic fashion. And as for his Hinglish—Gawd spare us!’

By now, Bruce had got into his routine. When he woke, which would often be in mid-morning, he would eat an elaborate breakfast of café au lait, baguette and a thick slice of white President French butter, topped by Bonne Maman apricot jam and Lindt chocolate. All of this would be specially fetched for him, according to minute written instructions, from a particular patisserie in Khan Market.

He would then get into his white pyjamas and sit on a cane chair in the garden, reading through the BL photocopies of his sources, under the shade of a wide-brimmed Cecil Beaton-style straw hat. He liked a small glass of wine, or often two, at lunch, and would often invite friends to join him. Our guest list and lunch parties always became much grander and more exotic when Brucie was staying. The elegant wives of ex-Sri Lankan Presidents, Iranian drummers, British Museum curators, Aligarh Mughal experts, Cambridge musicologists and celebrated Scottish botanists would all make their way out to the farm to see him. Those who were lucky would be treated to post-prandial readings of Persian poetry, accompanied by his translations, during which he might serve mango and limoncello, one of his favourite summer combinations. These lunches often saw him at his sunniest and, depending on the company, most wheezily giggly.

He would then take a nap, and by five pm, was busy in the kitchen instructing our amazing Bengali cook, Biru, who adored him, on the finer points of making petit-fours or drop scones or butter shortbread, all of which he loved for tea. This was a meal Bruce took with an Edwardian seriousness, serving it on trays with plates and silver and china tea pots. That done, he would then teach Sam Persian for an hour, encouraging him to learn by heart ghazals by Hafez, Rudraki and Sa’adi, long before Sam knew enough Persian to understand any of them. Often their meanings would only become apparent much later when, partly under Bruce’s direction, he began Persian at Oxford. Sam still knows them all by heart.

There often followed an evening gin and tonic with Olivia, when the two would set the world to rights. Intelligent female company always brought out the most private and empathetic side to Bruce, and Olivia was often privy to confidences I was only much later admitted to, if at all: a broken engagement soon after Oxford; the pain of his rejection by his father, who had named him after his favourite Labrador but showed him rather less affection, and who, at the end, cut him out completely from his will, leaving him nothing except for a pair of old brogues; his brief, unhappy—and most unlikely—period as a London tax-inspector; his much loved-sister’s suicide, and the memorial concert of Monteverdi madrigals he organised in her memory.

Finally, by seven or eight, he was ready to begin work. Unless he had arranged to go to a concert, he would usually skip dinner completely and work all night. Often we would return from Delhi parties long after midnight to see his light burning and Bruce tapping away on the laptop, his half-moon glasses perched at the end of his nose.

His main form of entertainment was to visit the various ruins of Delhi, to go to concerts, and to find pianos to play. He befriended our landlady, who had a lovely grand, and would treat her to evenings of Liszt and Debussy. Somehow Bruce also came into contact with a bespectacled American diplomat from Minnesota who was whispered to be the CIA station chief. The two played Shostakovich duets in a grand mansion under the yellow amaltas blossom of Amrita Shergil Marg, watched over by the American’s fearsome Kazakh bodybuilder wife. They made a most unusual threesome.

Bruce loved to drop hints about his friends in the intelligence services, and this was one of the questions I most longed to ask him at the end. We never did get to the bottom of exactly what he was up to in Peshawar, and the question of whether he was actually in Mi6 or just a translator and source of information on some outer periphery of that world. After all Bruce, for all his many qualities, made an unlikely James Bond.

Both my boys, Adam and Sam, loved to refill his glass and ask him about this period of his life. Sometimes, if they were lucky, he would tell them stories— of being chased through the plains of Afghanistan by Soviet helicopter gunships while riding pillion on the back of Mujahedin motorbikes; his regular visits to Peshawar banks to cash aid cheques and deliver suitcases stuffed with bank notes by mule train to the different Afghan groups in the Panjshir Valley; of being invited to lunch by Osama Bin Laden after he tried to get the Peshawar-based aid agencies to stick up for their Afghan staff who were being intimidated by the Pakistani police who would plant opium on them and then lock them up until they paid bribes to secure their release; his dislike of Gulbadan Hekmatyar, who he regarded as a vicious barbarian; of the night the ISI—so Brucie believed—assassinated his friend Juliet Crawley’s husband, Dominique Vergos, and how it was he who found the body hanging strung up on the garage door with an assassins’ bullet in the rear base of the skull; and the glimpse he had of the silhouette of the shooter disappearing over the compound wall in the moonlight.

This was actually a crucial turning point in contemporary history. It was the moment the Wahhabis of the Pakistani ISI and the Saudi General Intelligence Directorate seem to have broken ranks with the CIA and Mi6 and begun channelling their funding to only the most extreme Islamist groups among the Mujahedin. At the time of his assassination—and Bruce was always very clear that it really was an assassination, not a bungled robbery, as the Pakistani police insisted—Vergos was said to be compiling a dossier on the atrocities wrought by the ISI’s favourite client, Hekmatyar. The assassination was therefore the first time the Wahhabis in the intelligence community turned on their western allies. This was the beginning of the road to 9/11, and all that followed, and bizarrely, there was Bruce, caught blinking in the headlights, right in the middle of it all.

We longed to know more. But whenever we pressed him too hard he would just smile enigmatically, give a coy shrug of his shoulders, and say he had to get back to work.

IN DECEMBER 2018, my beloved father’s flame was ebbing and we all rushed back to Scotland to sit by his death bed.

Bruce was left in charge of the farm, with a full wood-shed and wine cellar, and instructions to help himself. When we returned, a month later, after the funeral, the farm was transformed. Both shed and cellar were completely empty, and the terrace outside Bruce’s bedroom had been turned into what were soon referred to as the Hanging Gardens of Bruce. Every pot plant and every palm, every brazier and every Moroccan lamp in the farm had been relocated to Bruce’s new open-air boudoir, where in our absence much merriment and many fine concerts of Persian music had been held, illuminated by blazing bonfires as well as the distant light of the stars. The pale moon of the winter solstice had been the occasion for a magnificently boozy celebration. From time to time, I still meet strangers who attended the party that night, and who compliment me on my beautiful roof terrace.

Soon after, Bruce began to complain of stomach pains. He had fallen and cracked his ribs the previous winter, so initially he was convinced it was something to do with that. Bruce could be very stoic about pain and discomfort, but he could also be something of a hypochondriac, and his emails and texts were often full of descriptions of ailments, major and minor. But as the year progressed, he began to get more and more certain that something was wrong. His father had died of pancreatic cancer, and he somehow felt sure it was hereditary. He promised to get checked out after he left Mira Singh Farm for the last time in April 2019, but delayed doing so while taking a last set of tours around various madly-dangerous conflict zones in Afghanistan and Iraq. On arrival back in York he sent a note which showed his suspicions:

‘Hello dear Willie

As always, it was a bit of a wrench leaving, I’d fallen into such a productive rhythm of long days with occasional escapes.

Thank you and Olivia for being so hospitable and such good friends. I left the flat-pack photocopies from the BL on your round table in your study. The Mir-Farsh paper-weights, are all on top of a cupboard in Ibby’s bedroom, out of the way till I get back: if for any reason I don’t, I’d like Samsam al-Daula and Adamski to have one mir-farsh each.’

He was in surprisingly high spirits that final summer, despite his growing anxiety and pain. He especially loved England in June and July, and my memories of that time of year are full of episodes dashing around the country from Arundel to Arisaig, chauffeuring Bruce to churches or concerts or country houses or operas, or usually, combinations of all the above.

Taking Bruce to the opera at Garsington became, in particular, something of an annual event. As always, he would sing for his supper, filling the journey there with stories of the composer or his music or how the opera came to be written and commissioned. He loved dressing up, and he loved music, just as he adored good company and good food, and outings to the Garsington Opera provided all of these pleasures at once. We went twice in the summer of 2019, once to Pelleas et Melisande, for which Brucie dressed up not in a dinner jacket but in a magnificent Afghan chapan, and once to the Monteverdi Vespers, which was dress-down, and for which he turned up barefoot, wearing a simple sadhu’s rudraksh around his neck. In the photos, he is laughing, as happy and relaxed as he had ever been, as if he did not have a care in the world.

But he knew something was badly wrong, and he waited nervously for his NHS appointment. After the launch party for The Anarchy in September, he sent a thank you note: ‘What a wonderful party,’ he wrote, polite as ever, ‘Congratulations on the finished chef d'oeuvre. I hope it will do really well—& thank you for your very generous acknowledgement. I miss our collaboration, & your company. I leave Saturday for Chechnya & Dagestan. Then into hospital to solve the searing stomach pains that have kept me from sleeping for the last 6 weeks—ulcers or cancer?’

As we all know, it was a particularly fast-acting and vicious version of the latter. On the 31st October, I woke in Delhi to find a terrible text:

Pancreatic cancer, far advanced, maybe 10 months left

They’ve promised pain-control, & a few months of active life

I’ve been playing baroque chamber music, to forget the pain

I’ll be sorry not to be around for our next project—thank you for stimulating friendship & collaboration over the last 20 years

LB

PS Please keep this to yourself for now’

We saw each other a last few times in December. My Company School show, Forgotten Masters, was about to open at the Wallace Collection, and I went around it for the first time with him on a bright, wintery Sunday morning, fresh off the plane from Delhi. He had lost a lot of weight, but was as elegant as ever, and appeared for the occasion in a perfectly tailored cashmere coat, topped with an Afghan lambskin karakul hat. He was high as a kite on strong doses of opiates, but was as brilliant and charming as ever, translating inscriptions on the paintings and dazzling the Wallace’s director, Xavier Bray, with the full beam of his charm and intelligence. Immediately after that, we had a last, long, hugely indulgent Christmas lunch together at his favourite gastro-pub, the Carpenter’s Arms. Towards the end of the meal, his face fell as he recited a Persian ghazal by Hafez, which he then translated for our benefit:

‘The night is dark, I am afraid of the waves,

This savage whirlpool terrifies me.

You who walk on the distant shore, light-burdened,

What do you know of my inner state?’

I saw him for the last time at the launch of Forgotten Masters. Bruce always loved a party, and he looked so happy, with all our mutual friends circling around him. We made plans for him to come and be pampered at the farm in January. We even hatched a plan to go to Dharamshala to see the Dalai Lama’s personal physician, which seemed an appropriately Brucie response to any illness. He was sure he would have another six months, and maybe one more glorious English summer full of operas and trips to his favourite abbeys, and he talked about getting tickets to a concert in the Chapter House of York Minster during the York Early Music Festival. But he went downhill fast after that, much faster than anyone had ever imagined. On the 21st January he wrote to say he probably would not make it back to India after all:

‘Dearest Willie,

Yes, the spirit is willing, but the flesh weakens more every day—I shall let you know when the candle is guttering finally, but for the moment, music is the best therapy—of which I’ve had daily doses here in London. It was good to play Mozart & Beethoven sonatas with Katherine. Henry also came from Edinburgh & we played piano duets: music takes the mind into different places.

Give my love to everyone on the Farm, especially Biru, Bina and Vijay. I miss you all, & must write to Sam & the Memsahib.

Back to York tomorrow, Macmillan cancer-nurses overdue to adjust pain-relief. The medication needs recalibrating, as it’s no longer controlling the pain, which is tiring, so I sleep a lot...

Saying goodbye to friends while I am still able to do so with some pleasure & in spite of sleepless nights. The kindness of friends has been beyond anything I could deserve. So heartwarming and comforting—& you one of the very best.

If doctors manage some remission for me, a visit to India might be possible, but for the moment I can’t stand or walk. I sleep much of each day. The prognostication or rather haruspication doesn’t go beyond 3 months, & I find it difficult to look beyond the end of my nose, let alone next week.

Keep well, dear friend, & good luck.

A big hug

Bruce died less than a week later. His last 24 hours were spent in hospital in York. He received so many visitors that he had to be moved to a ward all on his own to avoid disturbing the other patients. Up to his last afternoon, he was still planning a lunch party he wished to hold that weekend. Death ambushed him before he’d decided which of his prize Afghan mulberry puddings he would serve his guests.

May he rest in peace.

As he wrote himself: what a world is lost when someone dies!

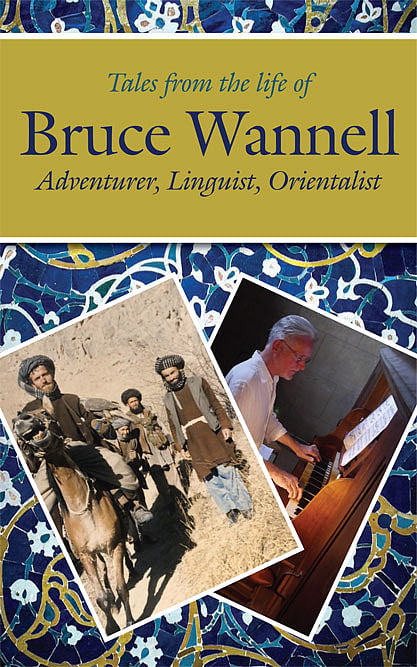

(This is an edited excerpt from Tales from the Life of Bruce Wannell; Adventurer, Linguist, Orientalist; Edited by Barnaby Rogerson & Rose Baring; Sickle Moon Books; 256 pages; £15)