The Business of Pleasure

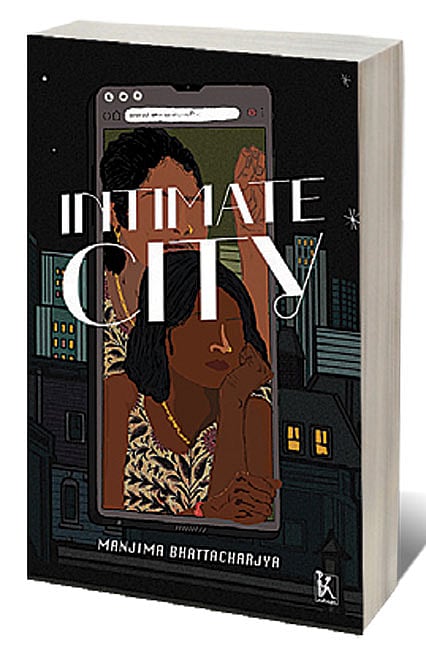

MANJIMA BHATTACHARJYA’S book Intimate City is an exploratory study about the diverse forms of sexual commerce in Mumbai. It is informed by her work as a sociologist, feminist researcher, and her involvement with the Indian women’s movement for over 20 years. It would be of interest to readers who are keen to learn about the lives of sex workers, bar dancers, massage boys and escort girls as service providers in an urban milieu.

Who pays for their services? Are they paid well? Where do they carry out their business? How are they treated by their employers, agents and customers? What else are they expected to provide? Why are they wary of meeting scholars who want them to talk about their lives in detail? The book tries to answer all these questions without passing moral judgements on the demand and supply in this sexual economy.

Bhattacharjya avoids any sweeping generalisations about how feminists view sexual commerce. She clarifies that feminist perspectives are rooted in experiences of caste and class that shape understanding of autonomy, consent and agency in intimate situations. Theoretical frameworks that are too dogmatic risk being out of touch with ground realities.

The author unpacks the tensions between feminists who believe nobody would enter sex work out of choice as it is inherently exploitative, and feminists convinced that one can choose sex work just like any other job. She wants her readers to think about what choice means in a neoliberal context, and in a society where women from oppressed castes have been expected to perform sexual labour for men from dominant castes.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The book engages with academic literature, news reports, and personal narratives collected via interviews with service providers and customers. It is concerned with the impact of gentrification on sex workers, the mushrooming of agencies to professionalise transactions, and the use of mobile phones to facilitate doorstep delivery. Bhattacharjya’s description of her methodological challenges during fieldwork would certainly benefit future researchers.

How does sex work compare with other livelihood options in terms of job profile, work hours, payment and financial security? What do service providers gain from presenting themselves as fluent in English, knowledgeable about fashion, and comfortable at parties? Why do cops respond differently to sex work carried out at massage parlours and in five-star hotels? Bhattacharjya does an admirable job of inviting the reader to reflect as they read.

It is a bit puzzling that she refers to sexual economies in New York, Bangkok, Vancouver, Tokyo and Oslo, but not to cities in Bangladesh and Nepal. Some inputs on that front could have helped connect the dots between migration and trafficking since the book does mention Bangladeshi and Nepali sex workers in the Kamathipura area of Mumbai.

Hijras, kothis and gay men exist on the sidelines in this book, as they do in patriarchal societies. The analysis is excruciatingly heteronormative, especially while discussing what constitutes sex. It is seen largely in terms of peno-vaginal penetration. This framework also shapes how the book speaks of violence in the context of marital rape and prostitution.

Intimate City makes a sharp, almost impermeable, distinction between offline and online worlds. This prevents the author from considering the screen as a venue for sexual commerce through sexting, audio-visual tools, geosocial hook-up apps, and self-uploaded amateur pornography. Service providers use digital technology not only to advertise and to fix appointments but also to provide services.

Bhattacharjya interrogates preconceived notions about who buys sex, and who sells it. She finds that men do pay for sex with other men, and that women participate in the sexual economy not only as service providers but also as customers. Unfortunately, when the demand-supply relationship is framed primarily as an exploitative one, it shames the disabled, the elderly, and the widowed who pay for sex work to fulfil their sexual needs.