Strangely Familiar

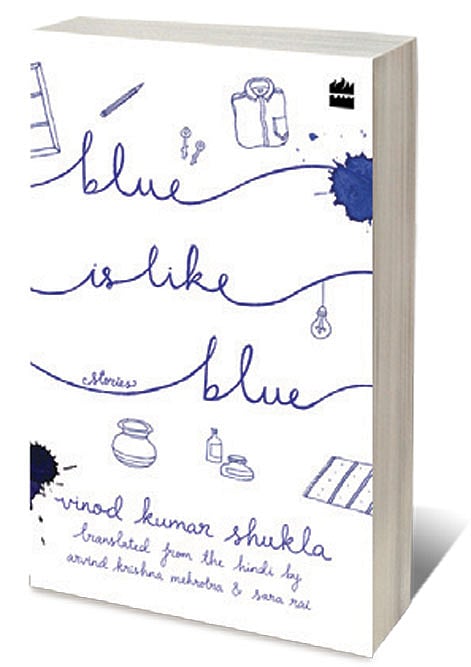

SO INTENSELY DETAILED is the writing of VK Shukla, so full of unexpected little observations and asides, that his stories bring the texture of a hyper-real dream to seemingly everyday incidents and musings. In College, the longest piece in this translated collection, we are told that a particular neem tree, seen in the dark, doesn’t look like a neem tree but ‘like some other tree dressed up like a neem’. A teacher walks half-bent, leaning forward: ‘If he had picked up something from the ground, no one would have noticed.’

In Piece of Gold, when half of a broken ring falls on a bed, the narrator stops his friend from getting up, because ‘if he got up the piece might get lost’; it is then found embedded in a crease. Such things, mentioned in passing, create a sense of a lived-in world: we feel we know his characters, mostly young men living in rented quarters, worrying about finances.

There is also the matter-of-fact anthropomorphising of things: living spaces, trees, colours, a marketplace. In Room on the Tree, when a young man locks his second-floor room to go to work, he feels ‘as if he had bound the room hand and foot, not that there was any chance of the room climbing down after him’. ‘Seen from the cinema’s point of view, I was just another cinemagoer,’ says the narrator of Old Veranda. The utensils in a household, bought second-hand, are named after old films like Duniya Na Mane.

It’s tempting to call these slice-of-life stories, but that doesn’t capture how they manage to be familiar and off-centre at once. At times, you might find yourself searching for the hidden core of a story (which may or may not exist). In The Burden, the title could refer to a leaf that becomes lodged in a young man’s pocket while he is cycling—or to the burden of a full month’s salary, which he has kept in his room, causing him to worry about theft. Also, despite the languid, undramatic tone, many of these stories are clearly about something: it’s another matter that they then find detours and cracks to slip into. As in Man in the Blue Shirt, which starts on a specific note—with the narrator intrigued by two sightings of a man wearing a blue shirt and carrying curd—but then becomes more abstract, as the focus shifts to other people on the road.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

You can start reading this book from anywhere, but it may be useful to trace Shukla’s writing arc. For instance, Fish, written when he was only around 20, feels relatively narrative-driven: the story has two little boys hoping to play with some fish that are to be killed for dinner, and there is a subplot about their unhappy elder sister. But even here, there is an unusual perspective on something that might otherwise be mundane: in the way, for example, that the smell of fish seems to fill the house on a day that a crisis has visited the family.

Some stories feel more allegorical than others. The Gathering is about poets and the literary symbols they use, which are then given physical shape and scrutinised by a pedantic critic. ‘There’s no mention in your poem of a dead snake with ants sticking to its mouth,’ this critic says, ‘You must change either the poem or the symbol.’

Is this a dig at artistic pretentions or at how creative people are expected to provide clear explanations for everything they do? In the case of Shukla—who, the translators tell us, was a provincial, ‘ground-hugging’ writer who seldom travelled, was puzzled by an elaborate autograph signing at a literature festival and had no idea who JM Coetzee was—it could be a combination of both. And for the reader who has never before encountered him, these stories can cause one to rethink what narratives should look and feel like.