Spittle Parable

A large, bearded man in a white Afghani garb appears at Bola Paan Shop after hearing about a spitting competition. His name is Dara Kosh Pathan, the eponymous Darako who has come from Herat. Parashar Kulkarni sets the scene: “Dara Kosh stops. He inhales. The sky turns dark. Moments later, his lips part. Sparkling spittle ripples through the air, illuminating the sky. It circles overhead like a shooting star and returns to Earth. Nearing its destination, it curves and enters the hole like a slithering eel.” He sets the record that will never be broken and just like he appeared out of nowhere, he vanishes, never to be seen again. So, his absence becomes the centre around which the book is then ordered.

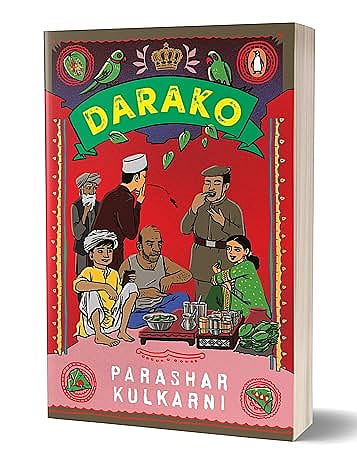

Darako is a strange, absurdist experiment by Parashar Kulkarni. Set in colonial India, it is mostly based at and around a paan shop in Bombay (now Mumbai). Quite slim at 140 pages, the independence movement and the struggle for freedom happens at the sidelines although some characters are actively involved in gunrunning while others are state actors whose job is to combat “sedition”. The novel begins when Bhola, the proprietor of a popular paan shop is paid a visit by an official of the British Chewing Gum Company who wants a surveyor to sit at the local haunt in order to study and report on the paan chewing habits of the customers. This surveyor, Bandu, becomes the other central character.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Neither Bandu nor Bhola are the narrators of this novel though. That honour goes to Peter, a nondescript police informant disguised as a mute beggar stationed outside the paan shop: “My job is to sit here with my eyes open and my mouth closed, and at the police station with my mouth open and eyes closed.” He is seemingly omnipresent and omniscient, on the outside of the action, peeking in and letting the reader witness it all with him. Peter overflows with wisdom and his unobtrusive narration, much like his person, adds character as well as a strand of philosophical musings that reveal deep insights about early 20th century India, its citizens, and human nature in general. He remains a spectator, not getting involved in the action unless he absolutely must—a scribe setting down a story.

With fame also comes dissatisfaction. Since Darako is nowhere to be found despite repeated efforts to locate him, some regular regulars in the competition start to believe that he is a figment of Bhola and Bandu’s imagination, created so that they would never have to give the winning pot to anyone else and can continue to mint money from bets and sales of paan. When Bandu is shot by one of the sceptics in a fit of passion, his death acts as a catalyst that spurs others. Bhola agrees to his partner’s parting words and vows to continue searching for Darako after taking the road of forgiveness. Bulbul, his lover, promises vengeance instead in a loud proclamation against everyone who had ever hurt him.

The novel does lose its direction towards the end where things move a little too much into the absurd. The timeline of the novel is not entirely clear although it seems that decades have passed from beginning to end. Kulkarni (who has received the Commonwealth Writers Short Story Prize and teaches at Yale-NUS College) is quite adept at dark humour and the tone of the novel elevates its content, casting some of its more serious themes, such as the grave violence of repressive state apparatuses, into relief. Other elements, where Darako becomes a God and Bandu his first martyred prophet leading to the establishment of schools and hospitals in their name as their followers amass, don’t land too well. However, the function of satire does not hinge on perfect meaning making and the form is used to the best of its ability to ably depict a topsy-turvy world of the past beyond the dusty pages of history.