Speaking from the Cloisters

GATHERING MANGOES. Eating jackfruit. Greeting visitors with conversation. Publishing poetry and prose. Putting out a CD of hymns. Securing a driving licence. Owning a car. This here is an abridged list of Sister Lucy’s crimes.

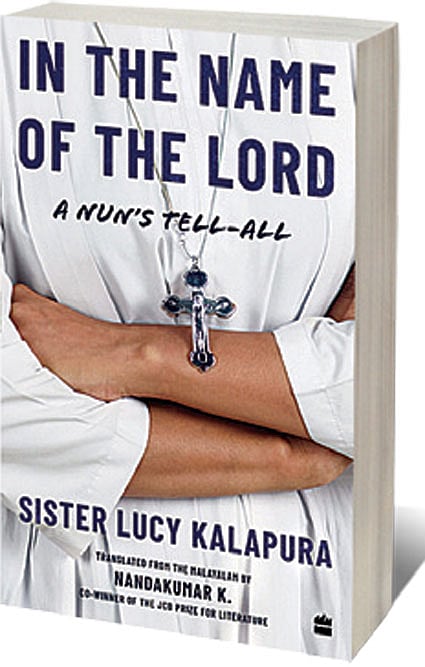

In her memoir In the Name of the Lord, Sister Lucy Kalapura writes, “My life seemed to be split into two halves.” Most know her through events from the second half of her life: her bigger “crimes” (speaking up against Bishop Franco Mulakkal) that eventually got her ostracised from the convent.

Translated from the Malayalam (Karthavinte Namathil) by Nandakumar K, the memoir is not so much an unpleasant read as it is unpleasant to read.

The translation at times loses sight of the reader. Consider these ill-shaped lines, unintentional in both effect and awkwardness: “I was intrepid. I was determined. My mind was made up irrevocably. It was not a wanton desire born in a fickle moment.” Or “Gossip and obloquy against me were rife and rolled in wave after wave.”

The peculiarly flashy translation often sacrifices substance for sensationalism. Rather it retains the sensationalist packaging that such books are often furnished with. Not to mention the tired tagline accompanying the book’s title—“A nun’s tell-all.” If you are familiar with Sister Lucy’s story you will know it to be a straightforward one. Unsettling, yes, but still straightforward to those of us who have grown up with churches and families that tutor us into being manageable parishioners. When the child Lucy chances upon the vicar fondling and caressing a schoolgirl, her mother cautions her—“forget about it.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

As a child, Lucy wants to mimic her grandfather, Kalapurakkal Scaria. This attempt at approximation continues even in the book she writes as an adult. Described as “a dapper gentleman” with an “an imperious bearing,” Scaria’s most symptomatic trait is that he sometimes likes to buy fish only for himself and often requires his food be prepared in “different styles.” One wonders why anybody would want to emulate a man with such strange habits. But what begins as unrelenting esteem toward her grandfather slowly reveals itself to be Sister Lucy’s determination to parallel men in the respect they so effortlessly secure.

Sometimes, Sister Lucy has exacting moral codes laid down for her peers. It baffles her that nuns (and priests) should feel jealousy and envy or hold grudges and spread gossip like ordinary men and women. Sister Lucy’s hardened morals rarely obstruct sympathy. But in 2022 a Kerala court wielded the “in-fight and rivalry and group fights of the nuns” among its reasons to acquit the bishop. When nuns behave like lay people, do they lose their rights to a fair trial?

Often, Sister Lucy eases into verbose anecdotes and phrases that betray caste pride among Syrian Christians in Kerala. Where the Tamil writer Bama’s Karukku is sharply perceptive to how caste takes shape in Christianity, In the Name of the Lord is at times lacking. Consider this line for example, “The nuns were elated. They were pleased that they had managed to draw a member of the well-to-do and reputable Kalapurakkal family to their fold.”

Intermittent Bible verses populate the narrative. Like bookmarks, they seem to be careful inserts to guide Sister Lucy. The older Lucy lives by these pockets of assurances. She writes about feeling no guilt even when pronounced guilty. She endorses a redesign of the nun’s habit—far too impractical in Kerala’s heat and humidity. She coolly declares that the “thunderous evangelism of Shalom TV” hardly moved her.

In Sister Lucy’s writing, you sense the profound isolation felt by someone who spent decades of her life abiding by the church and convents only to be cast out. But we also see an outcast revived by the friendships she discovers through her protest and resolve to be heard.