Siddhartha Deb: Flying Mughals

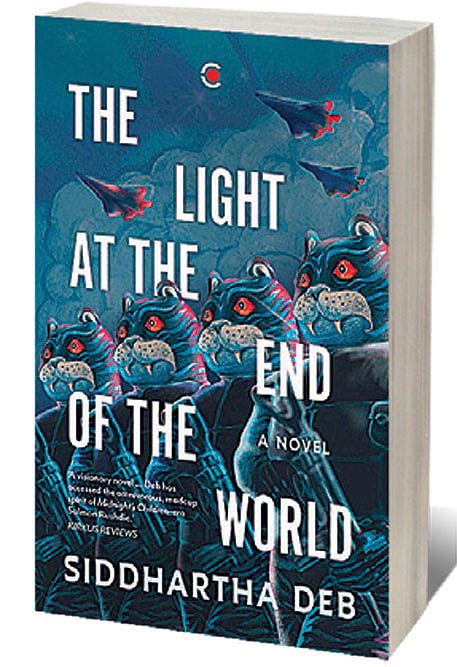

IT’S HARD TO pin down Siddhartha Deb’s new novel The Light at the End of the World (Context; 458 pages; ₹799). A door stopper of a novel, it organically embraces genre-hybridity like late-stage millennials with their vape pens. It’s a novel where dystopia meets imperial gothic and colonial historical fiction to breath-taking effect.

“I wanted the reader to think, ‘Wow this is wild,’ which is not the reaction people have when they read South Asian novels,” Deb says over a Zoom call from his New York residence. Unsurprisingly that was the effect it had on Carl Bromley, an editor-friend of Deb’s and one of the first people to read the manuscript, who asked him what he was smoking when he wrote it. Deb is the author of three previous books including the well-received non-fiction The Beautiful and the Damned (2011) and the novels An Outline of the Republic (2005) and The Point of Return (2002).

Spread across four novellas, loosely connected with each other, The Light at the End of the World jumps across timelines, people and events, trying to anchor itself to a common ground and often emerges successful in doing so. The patchwork of standalone narratives that populate each section are inventive and bring forth the idea of a perhaps unforeseen India. Its protagonists range from hapless journalists to contract killers and white Mughals to colonial foot soldiers. Everyone is in a quest for something that consumes them.

Deb claims he wanted to break the notion that South Asian novels are respectable and nothing scandalous ever happens in them. “I was writing with all these fantasies one has about writing a very smart, intellectual and brilliant novel but I was running away from being termed ‘respectable,’” he says.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In the first section, in a prose breathless and urgent, reminiscent of early Salman Rushdie’s magical realism, Deb’s characters navigate a Delhi set in the near future. Bibi, the protagonist, an erstwhile journalist who’s now employed at a mysterious consultancy called Amidala that produces reports on sundry topics for influential organisations, waddles through her life as things seemingly crumble around her.

It’s the starkest picture presenting the decay of the society, caught in the throes of an ethno-fascist state. Divisive policies— demonetisation, citizenship amendment, privacy laws, farmers protests—everything is in here. Delhi is as much a character in this section, albeit not a desirable one.

Resilient Bibi could be the poster girl for millions of Indian women who have struggled to stand their ground in the lonely fight against patriarchy. Except she’s not. She is tasked by her employer to follow the trail of her ex-colleague with whom she wrote a critical piece in the waning days of her journalism career and who is supposedly a national security threat. Her phone receives a barrage of abuses, her citizenship is thrown into question as her Aadhaar application is flagged, and her ailing mother’s care threatens to fall on her.

Deb says he was more interested in Bibi’s psychology and not in straightforward realism, rendering the section a grittiness that blends multiple conspiratorial allegories, set in a shadowy alternative future. “I very much wanted to play with things you can’t do in journalism, which is twist reality with imagination and fantasy,” he says.

Before the handwringing about ethno-nationalism in near-future India overwhelms the narrative, the book leaves Bibi to her own devices. It leapfrogs to the equally breathlessly paced second section where an unnamed narrator, a hitman, is assigned his next target in Bhopal by his mysterious patron. Bhopal is on the cusp of a devastating Union Carbide incident—a combination of pathological negligence by the company and government apathy.

The narrator follows his subject, and the reader gets a front-row seat to witness the web of capitalistic greed and corruption conspiring to jeopardise the future of unsuspecting people. “Insect people all around me,” the narrator says with disgust even as he sets off on a brief affair with an incense maker’s widowed daughter in her dwelling in a slum.

Deb says the disturbing character of the nameless contract killer appeared to him on the train. Initially shocked by its audaciousness, he continued writing it because he thought, “It was an interesting challenge, aesthetically, politically, imaginatively, to put myself in the head of somebody with whom I will probably have no sympathies at all.”

As he has written about Bhopal before in nonfiction and it troubles him, to take an angular, unsympathetic voice was exhilarating for a writer, he claims. “That’s the kind of thing you can do in a novel. I thought it was great to go there.”

When the book leaves Bhopal, it’s to travel back to 1947 and the British have just yielded to the independence movement. Das, the protagonist of this section, is being asked to hand over the vimana—an anti-bomb aircraft using the ancient manual Vymanika Shastra—he’s been working on, by the British. In Byomkesh Bakshi style, the narrative spins in and out of Kolkata as the city is undergoing a historic transition. In what is the most speculative of all the chapters, the quest for the vimana becomes a metaphor for supremacy, a tired trope that ruled the narrative on the political right in India but refuses to recede because of its currency.

Switching between these universes can sometimes overwhelm but blending genres to create this mélange of narratives syncs with Deb’s best laid plans. Admittedly its composition was also not without its challenges; “some parts were harder but some wrote themselves,” he admits.

In the penultimate section, we encounter a colonial battalion where Skyes is the lead soldier alongside Colonel Sleeman, in search of Magadh Rai, a conspirator of the sepoy mutiny. Traversing the lifeless stretches of Cooch Behar, the battalion encounters a white Mughal who claims he’s been driven out of his kingdom by the “native brigands”. Setting aside the battalion’s immediate mission, they embark on a journey to the white Mughal’s castle to recapture it for him. But at the palace filled with bizarre souvenirs including a clockwork tiger and automaton sepoys, there’s menace in the air and Colonel Sleeman is quick to indulge in the local traditions of voodoo and black magic along with the white Mughal in the palace’s Ajaib Ghar. This section of the book firmly positions itself in the tradition of imperial gothic characterised by the European fear of going native in India, while Skyes passes languid day after day in the kingdom, with his battalion having lost its purpose and direction.

Reflecting on the hybridity of the narrative, Deb says, “The thing about genre hybridity is that it’s against the idea of the pure. Fluidity is something I think is intrinsic to storytelling and life itself, in some sense.”

Insofar as Deb’s greatest preoccupation about the novel is concerned, he wanted to write a South Asian novel not steeped in realism. “I felt that fiction from the region doesn’t quite capture the weirdness of life in India. I wanted to read a kind of South Asian novel that had conspiracy, paranoia and shapeshifting because a novel twisting genre with realism is very liberating,” he claims.

Across seven summers while he was on break from teaching and the occasional freelance journalism, Deb says he dedicated time to write the novel. To keep track of the numerous characters weaving in and out of the sprawling narrative, he used sticky notes neatly stuck on the back of a massive white board his son used to play the Saboteur boardgame. He also swears by Scrivener that he started using for his 2011 book The Beautiful and the Damned: A Portrait of the New India and finds it “really great,” for managing a complex narrative with lots of arcs, characters and parts. In addition, a stubby black moleskin notebook helped him keep track of all the additional notes.

While he wrote, he read everything from early Rushdie, Gabriel García Márquez to Thomas Pynchon to Rachel Cusk to Rachel Kushner and Japanese giants like Yukio Mishima and Haruki Murakami. Additionally, “Qurratulain Hyder’s Fireflies in the Mist was a very important novel, but people don’t seem to know her in the West. Agha Shahid Ali’s The Half-Inch Himalayas is talismanic in its importance for my novel,” he adds.

As The Light at the End of the World draws to a close, multiple universes collide. The sprawling prose that begins with a state-of-the-nation narrative, rolls into colonial history, progressively steeping itself in the imperial gothic style and ties everything together with a dash of speculative fiction. Held to closer scrutiny, its intertextualities form a delicately spun web, which is at once captivating and original. As to what he was smoking while he wrote it, Deb only guffaws conspiratorially.