Shades of the Sheikh

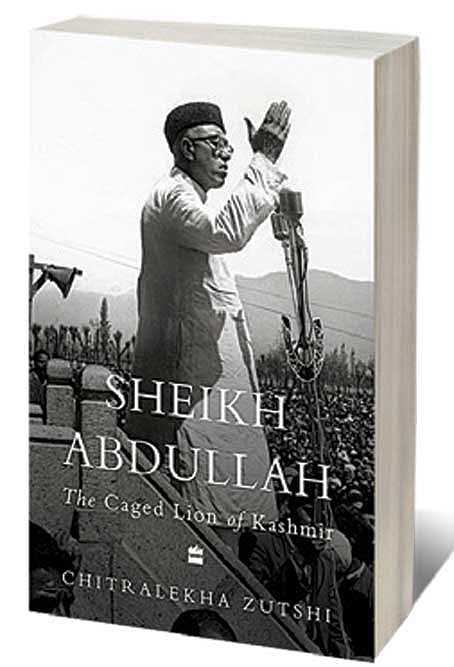

THE CAGED LION OF KASHMIR is an important book for many reasons. Most obviously because it seeks to acquaint us with Sheikh Abdullah, Kashmir’s tallest (literally and metaphorically) leader whose importance and political footprints far exceed the scholarly attention he has received. The book daringly forays into the dense jungle that is Kashmir politics to locate its “Lion” and chronicle his personal, political and paradoxical life in a manner that is at once, reflective, empathetic and unsparing.

Kashmir is no ordinary place: its turbulence, tumult, tragedies would have few parallels on this planet. It wasn’t possible for its biggest leader to remain unscathed by the labyrinth of its myriad, unsparing conflicts and contradictions. If Kashmir is a tragedy, Sheikh Abdullah is its most tragic hero whose misfortune was brought about not by vice or depravity but by, borrowing from Aristotle, “some error or frailty”. The book skilfully sketches Abdullah’s “fatal flaws” to reveal the political, cultural and affective aspects of Kashmiri nationalism. Such is its sweep and so deft is its navigation through the tangled web of Kashmir politics that this biography rightfully qualifies to be what Stanley Wolpert said in his 2010 essay: “At its best, biography is the finest form of history.”

It is to author Chitralekha Zutshi’s credit that she centre-stages this morally ambiguous figure amidst Kashmir’s search for identity and sovereignty. The subsuming arc of Indian nationhood, Pakistan’s counter claims and constant interloping into Kashmiri affairs, the residual tremors of Cold War, intersecting strands of American and Chinese interests in the region—together structured, as also stymied the arc of Kashmiri nationalism. Abdullah became its best-known symbol and its most conflicted manifestation, “a perfect embodiment of the abject failure” of all plans and aspirations.

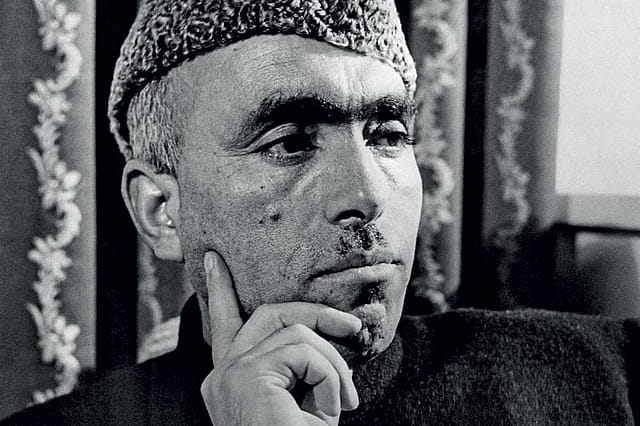

GM Sadiq, chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, had said of Abdullah in 1966: “Abdullah’s words always had a double meaning.” Perhaps it was because Abdullah embodied a bunch of contradictory traits. He has been described variously as both naïve and shrewd, saviour and oppressor, secular and communal, true patriot and Pakistani agent, India’s lackey and Kashmir’s Gandhi, tall-leader and a “tall-fool”, messiah and as a Frankenstein who created the “monster of Kashmiri nationalism”. Abdullah had the schizophrenic ability to be both, as well as neither.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Zutshi’s task is further complicated as no two faces of the “web-characters” are steady in either their appearance, intent or their relation to each other. Nehru was both Abdullah’s ally and captor; Abdullah was betrayed by both GM Sadiq, a close colleague from early days, and by GM Bakshi who eventually joined hands with the Congress to diminish Abdullah’s relevance. Abdullah’s closest associates and allies—Mirza Afzal Beg, Balraj Puri, PN Bazaz among others—drifted away and fell out with him, often with good reason.

Zutshi traverses a web of motives, designs, hopes, betrayals, intrigue, treaties, agreements, movements, persons and personalities with the deftness of a skilled historian and the fairness of a good biographer. But what is indeed noteworthy about her skill is her ability to elicit from her readers a range of emotions. Much like books in the tragedy genre, The Caged Lion evokes feelings of admiration, frustration, disbelief, sadness, lament and support for this “successful failure” called Sheikh Abdullah, whose “vacillations between being a secularist in India and an Islamist in Kashmir had left all sides unsatisfied.”

There are two aspects of Sheikh Abdullah that struck me as having a decisive bearing on his politics. The first was his own personality and persona which made his politics and administration, as Ramachandra Guha describes in the foreword to the book, “arbitrary, capricious and intensely personalized”. Abdullah’s regime, Zutshi explains, “came to embody that vision of democracy in which a supreme authoritarian leader gives voice to the popular will without the intercession of institutions such as political parties, unions, and the press.” This not only made him both loved and loathed, respected and reviled in equal measure, but importantly and unfortunately also weakened the legacy of his principles and ideology, the core of which rested on an abstract idea of Kashmiri self-determination.

The second aspect of Sheikh Abdullah’s politics was governed by his location. Way back, Karan Singh the newly appointed regent of Jammu & Kashmir in 1949 had said quite accurately: “[T] basic difference between Sheikh Abdullah and me lay in the fact that while he looked upon himself as a Kashmiri who happened to find himself in India, I considered myself an Indian who happened to find himself in Kashmir.” It is this location, rather the perception of the location that drove and altered Abdullah’s political priorities with time and from time to time. It ranged from being instrumental in effecting J&K’s accession to India, to questioning its veracity; from leading the Quit Kashmir movement (to rid the Kashmir Valley of autocratic Dogra rule) to the plebiscite-movement as a means to secure autonomy for the Kashmiris; and finally from being one of the persistent votaries of plebiscite, to making a “Faustian deal” with Indira Gandhi that left him with no choice than to accept the state’s accession to India.

Balraj Puri, once member of the National Conference, supporter, ally captured the central dilemma that shaped Abdullah’s political life: “How was he to balance his stature as a representative of Kashmiri nationalism while remaining a loyal Indian who did not question India’s absolute sovereignty over Kashmir?”

In essence this is the core dilemma of a regional-vernacular-particularistic nationalism that struggles to keep itself distinct and relevant in a post-colonial nation. Abdullah’s “sahi quomparasti” (correct patriotism) enabled Kashmiris to continue their struggle along nationalistic lines, but it also ended up blurring the lines between federalist aspirations and nationalist integration. The blurring began formally with the Haripura Resolution in 1938, became fuzzier with the Delhi Agreement in 1952, and reached an acquiescent compromise with the Indira-Sheikh Accord in 1975. By 1984, to quote from the book, “Kashmiriyat, Kashmir’s tradition of communal harmony and syncretic religious culture…became a dirty word held responsible for bringing Kashmir to this pass by forcing upon it a sub-nationalistic identity acceptable to India.” The book chronicles this journey of how Abdullah became both a participant in, as well as a victim of, the postcolonial state’s agenda of integrating and centralising its diverse territories. This “insurgent subject” became both the face of a post-colonial state’s anxiety “as well as the sole means of their alleviation”.

Postcolonial anxieties about nationhood, territory and sovereignty express themselves most palpably and virulently at its frontiers. The cartographic lines demarcate nations and their territories but identities and affinities remain fluid and transferable across these mapped lines. In a collection of essays published in Seminar in 1964, Surindar Suri in his article had noted that discontent and desires being expressed in Kashmir were not unique and that many regions experienced a similar angst against the Indian state. What made Kashmir unique was that it was a frontier state, had Sheikh Abdullah, and had an alternative. However, rather fortuitously, he had also predicted that “Kashmir today is the mirror of India’s future”.

It has been a constant and loud lament of a section of educated Indians that recorded and written history has been deliberately selective. But the irony and a measure of this indignation itself being selective, is that the invisibility of Kashmir’s history finds no outrage-constituency. Well, here is a book that seeks to make Kashmir and its many paradoxes and tragedies visible. For those not content with quick answers and easy remonstrations, for those who do not dive into history to find enemies, locate scapegoats and fix culpability, and for those genuinely wanting to know and learn about Kashmir: this book needs to be on your bookshelf.