Self and Others

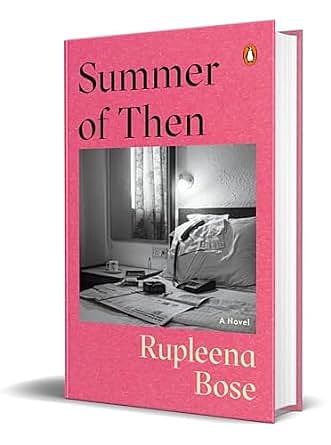

In Rupleena Bose’s debut novel Summer of Then, an unnamed literature and film studies academic and aspiring writer contemplates the shape of her life, parsing it initially through the lens of relationships with two men, who form a pair of friends—Nikhil and Zap. As the years turn into decades, the protagonist’s primary relationship grows to become one with her own selfhood, as she begins to grasp her life as it can be beyond sex, trauma and disappointment. First, though, there is longing, and from this longing are spun insights into how sociopolitical maturity can elevate the ordinary life into one of meaning.

There is a sentimental moment near the beginning of the book, when the protagonist sees a glass bead on a stair and decides against picking it up: “It could live on, growing old in Zap’s childhood house with the memory of this smoky night”. Replete with details like these, the novel often has a moody, cinematic quality.

While atmospheric, the prose does contain a frequent mixing of tenses, and it’s unclear whether this is a glitch or a feature. For instance, the grammar in this representative sentence sequence is baffling: “I want to get up and leave the room, but I could not. The cold steel clock ticks into the silence between us. It is like playing a game that had no end.” It is unclear whether this confusion between tenses reflects the protagonist’s melding of memory and present experience or is just poor copyediting.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Summer of Then’s power is in its subtlety. The protagonist’s interior life carries myriad reflections that go beyond it. While never polemic, her positionality as an ambiguously non-upper caste, middle class woman is intelligently used by Bose to delineate dynamics in the cultural world, with astute observations on artists who choose their personas for the day, foreigners who only live in India during the best seasons and the precarity of being an Indian artist without generational wealth. Beyond messy relationships and incestuous social circles, dramatic events too occur simultaneously on a larger backdrop, without being a stretch—like her household staff Dharamdev’s escape of communal riots and subsequent identity concealment, or the murder of one of the protagonist’s students for loving another student across religious lines.

Through the course of the book, the protagonist moves from being an average, educated, English-speaking, urban Indian woman with creative inclinations to one who has considered the real roles of feminism and progressive politics in her ordinary life. The reckoning begins when she discovers that a teacher of hers from school had named her in an article, thus outing her as a sexual assault survivor. It continues when she marries one of the two men she has long been obsessed with, and finds that marriage—even a marriage with infidelity—is suffocating. Other women she meets constantly make strange or smart choices within acceptable paradigms. Marriage makes a boring woman out of her—even the narrative flags for a bit here—but freedom is found in pursuing her writing, and travelling abroad.

There, she realises that in places of less systemic inequity, even a mediocre life can be a good one. She returns to India having released some of her shackles, no longer seeing herself as unimportant, and galvanized about both her teaching and her creative work, which draws from her late grandmother’s unsung personal history in a newly independent India. It’s the honesty of its last section, with lines like, “I wish I could tell her she was lucky. Lucky that she is not a woman who was born in an ordinary family in India,” that makes this novel shine. Beginning in a ruminatively subjective way, it expands gradually to become a story of many: a story of how a nation and its societies have failed even the more privileged of its citizens, and then a story of hope—of setting oneself and others free.