Searching for Mr Munin Barkotoki

THE GREAT THING about bibliomania as a plot point is that it opens up avenues for what philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari call ‘rhizomatic’ growth: an endless array of narrative roots growing outwards from the story’s core. When obsessed by a writer or a book, bibliomaniacs tend to be completionists. They won’t sleep well until every single bit of information in the public domain about the book/writer has been extracted and filed for the future. It’s why Roberto Bolaño’s novels like 2666 and The Savage Detectives work so well (and why his relatively slimmer works don’t). The ever-accelerating polyphony is rather the point—it’s called bibliomania, not biblio-normal-and-super-healthy-relationship.

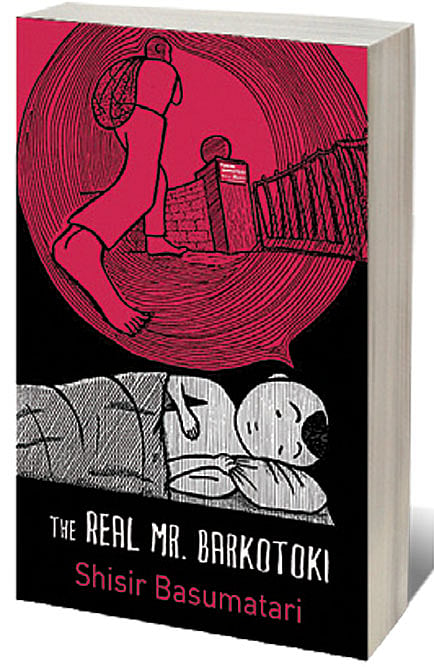

This is also why I loved Shisir Basumatari’s new graphic novel The Real Mr Barkotoki: it understands the obsessive frame of mind that fuels Bolaño-esque literary quests. The unnamed protagonist here has a recurring dream about a Mr Munin Barkotoki and soon realises that he’s having visions of the late, real-world Assamese writer of the same name. With the help of his eccentric friend Dr Das (a psychiatrist) our hero tries to get to the bottom of his vision and what it means for his future.

The quest to find Mr Barkotoki allows Basumatari the narrative opening to explore questions of consciousness, experience, memory and the act of retelling. For example, when Dr Das employs hypnosis to extract more images from the protagonist’s dreams, an extra detail emerges. This is the book, God Bless You, Dr Kevorkian, a collection of fictional interviews by Kurt Vonnegut where he imagines euthanasia advocate Dr Jack Kevorkian giving him a near-death experience that allows him short-term access to heaven. Vonnegut then interviews dead writers like Isaac Asimov and William Shakespeare—significantly, these ‘interviews’ were first released on radio. Similarly, Basumatari’s protagonist dreams of an old radio interview where Barkotoki is talking about his work and his influences. The entire sequence is audacious and well-executed.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Visually, too, the book has eye-catching tributes to both Indian and international comics artists. There is more than a little of Joe Sacco, as the back cover itself promises, specifically Sacco’s obsessive cross-hatching in works like Palestine and Footnotes from Gaza. The protagonist’s dream involving Barkotoki is a silent sequence, where he sees himself as a young boy with a shaved head and the classical Brahmin ‘shikha’ or ponytail (once-popular among communities like the Namboodiri Brahmins). Later, when the protagonist tells a mask-maker to create a mask resembling the face from his vision, he says, ‘It should make me look young and mute.’ Both of these moments—and the Brahmin-boy visual style—are reminiscent of Appupen’s Halahala stories (Moonward, Legends of Halahala and so on), where there are quite a few wordless dreamers with shaved heads and shikhas.

There are, however, minor inconsistencies along the way. The writing is a little too cryptic at times and has some way to go before it catches up with the art. In order to achieve the Rs 499 MRP, the dimensions have been made maybe 20-30 per cent smaller than what the art demands. Things like this are doubly important with graphic novels, where the book-as-artifact aspect really kicks in. Even Joe Sacco, quite clearly Basumatari’s artistic role model here, favours a much larger size of book (think Footnotes in Gaza, which is 1.5x taller and a bit broader as well) to properly show the cross-hatching and the lettering that resembles horizontally cutout newspaper strips (which Basumatari also pays homage to here).

Overall, Basumatari’s is a promising debut. Indian comics fans would be well-advised to follow his career closely.