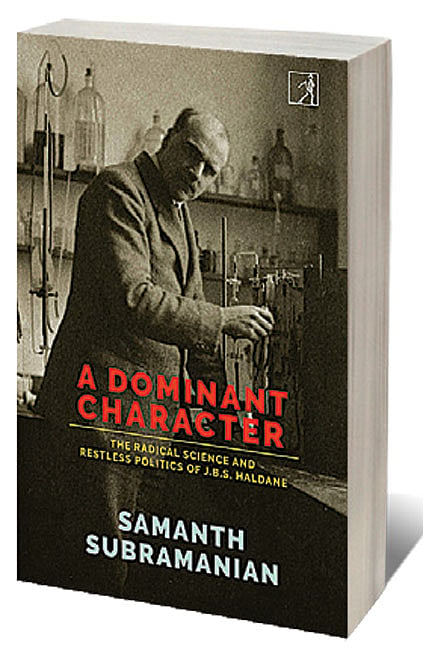

Scientist as Socialist

THIS IS A rare biography that is about both a life of a figure of science and the milieu that nurtured him. But it goes even further for this was more than a Darwinian preacher or a scholar who anticipated the intertwining of mathematics and biology or genetics and life sciences. JBS Haldane was very much a rebel against the patrician world he was a product of, a Marxist whose beliefs were honed in the inter-war world and firmed up in the struggle against the Spanish monarchists. He threw himself with all vigour into the war efforts against Nazi Germany but remained an unrepentant socialist in the Cold War years. In common with other Cambridge men such as JD Bernal and Joseph Needham, crystallographer and Sinologist respectively, he marched to the beat of his own drum. This book makes the man and his times come alive.

None of this would work were it not for the lucidity of the writing, coupled with the hard work in as many as 18 archives worn lightly on Subramanian’s sleeve. Haldane’s years in Cambridge and in the laboratories and corridors of British science ended when he abruptly at age 65 came to India. But as the book shows he was still young at heart, searching for a society where ideals could rule and India, where he died, with all its disappointments, still gave him that sense of purpose long after he was at a loss with the changes in British society and polity.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The appeal of the book is in the way the two key words in the title relate to each other in Haldane’s life and work. He was restless as he relentlessly asked and sought answers to questions. But this is at the heart of all enquiry whether in the arts or the sciences. What set him apart was that he was both scientist and radical and he saw these as part of a seamless whole. Despite his patrician roots and upbringing and his First World War experiences in present-day Iraq, he was willing to go where few upper-class English men or women would go. The power and appeal of socialism would eventually take hold of many a fine mind in the Cambridge of the 1930s and Haldane was to be among the most prominent and famous.

What is fascinating is the way in which this precise period in his life coincided with his rapid ascent as a scholar breaking fresh ground. Already regarded as a ‘walking encyclopedia and academic of rare uncommon quality’, his felicity with mathematics enabled him to write papers that would today rank as citation classics. That ‘an ounce of algebra is worth a ton of verbal argument’ is common place in the natural sciences today but was a mint fresh idea in the 1930s. Genetics, biochemistry and physiology were among the fields where the young biologist made a mark. This ‘hot streak’ of publications—10 between 1924 and 1933—laid the foundations of the entire field of population genetics. But while diversity in the peppered moth was a subject up a biologist’s street it was typical of Haldane to write a paper on the composition of the atmosphere of Jupiter.

Yet, nothing, not his First Degree in the Classics or his subsequent career in biology, could account for his radicalism. He had been harshly critical of the unequal distribution of wealth as early as 1928, but veered much more to the left soon after. Subramanian rightly asks why a man of such rare sensitivity and intelligence was blind to the show trials in the Stalin era that began just weeks before Haldane’s own trip to the land of the Soviets. Others (from Bertrand Russell to Nehru) remained deeply sceptical of the muzzling of free speech. In Haldane’s case his brilliant columns in The Daily Worker would, for years, see Moscow as showing the road to the future. So much so that he was silent when the great plant geneticist Vavilov was purged.

Haldane’s own personality marked him out in a crowd perhaps even more than his politics. There is yet something in the rebel in the professor that evokes a charm all of its own. Quitting Cambridge in 1932 he worked in University College, London. When asked to submit a report to a council, this incredibly prolific scholar penned a poem. ‘But I have you on toast/ For I shall not retire/ Till I’m offered a post/ AT the same pay or higher,’ he wrote. The sting was in the tail where he said, ‘And a person of my reputation/ you haven’t the courage to fire.’ This was long before he had turned a committed Marxist.

Haldane’s pioneering early applications of science on the battlefield in Spain to save the lives of the Republican soldiers and civilians alike from the worst effects of bombing and shelling were to stand him in good stead when Britain was at war. His work on air raid shelters and equally so his courage during Luftwaffe air raids made him widely admired by his countrymen and women. The wonder of the UK’s archives and open access rules show how closely snoops had watched the professor across the years. To be fair, and here Subramanian’s direct quotes from the files are hilarious (and literally comical) more often than not, they found he was a first-rate intellectual of firm beliefs but by no stretch a traitor.

Yet even in the post-Stalin years he still admired the charlatan Lysenko who reduced Russian genetics to an ideological morass at the cost of fine, gifted scientists. Here, as the author shows, Haldane was in the company of fine minds who let ideological blinkers overcome their innate questioning of authority in their own society.

In this latter role, he was second to none. Haldane exited British academia in the wake of Antony Eden’s disastrous Suez adventure in 1956. For Haldane, it was the last straw. He had visited India in the winter of 1951-1952 when the country was in the throes of its first General Election. Typical of the man, he delivered 35 lectures in seven weeks. Nehru and the blend of democracy with socialism, as much as the advocacy of peace in the world arena, attracted him to India. His tenure at the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) did not end happily as he clashed with Director PC Mahalanobis. These were two men with two egos too large for one small cage! But when he left he took an offer in Bhubaneswar. He had already taken up Indian citizenship and saw his future in his newly adopted land.

The admiration for India had a larger context as had his earlier love for the Soviet experiment. It is easy to forget that the 1950s were the time of the first nuclear-arms race, of McCarthy in the US and the start of largescale funding of varsity research for the military-industrial complex. Much of this did more than distress Haldane. If his blinkers had been on with the excesses in the East, he was outspoken in his views of the West in the new world of the Cold War. This needed rare courage, more so in a man of his class and background.

India was no paradise but he took the struggles with the bureaucracy in his stride. The ISI years were tough on him. The contracts and fine print were unrelenting. He could not speak on political matters or buy any equipment for more than Rs 10 without sanction.

He died in August 1964, a scientist with a voice all his own. Haldane emerges in this book a more luminous and textured figure but also one who straddled many branches and spheres of knowledge. This is a gem of a book where the easy turn of phrase comes with rare insight.