Sathnam Sanghera: The Empire Raider

CHANGE, AS THEY SAY, happens gradually and then suddenly. In the span of a book, an author can go from affirming that he is “not a historian” that he is a “journalist and author” to asserting that he is all three. In 2023, London-based journalist Sathnam Sanghera wrote a snappy children’s book based on his bestseller Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain (2021). In the introduction to his children’s book Stolen History: The Truth about the British Empire and How it Shaped Us, Sanghera eschews the title of a historian, and reveals that history “bored him to tears” in school. He did not even study the subject beyond the age of 16. What changed? The realisation that the British empire explains so much about our lives. He, thus, embarks on a journey to educate children about empire, believing “if we learn the truth about our past, we can make better sense of the present and future.” “And also fight for a kinder and fairer world.”

Fast-forward to a year later. During a recent interview with Open magazine, the 47-year-old, who has also written a memoir and a novel, proudly embraces the title of a historian. What changed? Empireland is being used as a teaching resource in hundreds of schools across the UK. Even Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London, has said, “I only wish this book was around when I was at school.” Sanghera was even elected a fellow of the hallowed Royal Historical Society in 2023. Speaking from London, he adds, “I say I am a historian because it pisses off my enemies. You can call me a journalist. You can call me a novelist. I don’t care. Just judge the writing.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Sanghera has pissed off a lot of people with his writing on empire, and his conclusion, “The British empire is the single most influential incubator, refiner and propagator of white supremacy in the history of the planet.” His exploration of the legacy of empire has received a virulent backlash in Britain. In June 2023, The Guardian reported, “Abuse has led Sathnam Sanghera to ‘more or less stop’ doing book events in UK”. He is in fact more comfortable at international events like the Jaipur Literature Festival, which he attended in 2023, and where he found the audience both knowledgeable and curious. The abuse showered on him by bigoted nostalgists in the UK is, unsurprisingly, empire related. And it is particularly severe because he is a British national born to Punjabi parents in the West Midlands, living in London, writing of empire. Historian William Dalrymple has underscored the fact that while writing of similar themes as Sanghera he has not received a “single piece of similar hate mail from a British person in decades”. Whereas Sanghera receives hundreds, if not thousands, of online abusive posts and letters. While the abuse has taken a personal and mental toll on Sanghera, it has also spurred him on.

Addressing his naysayers, he announced the arrival of his latest book Empireworld on Twitter in 2023 with the post; “News. I know from abuse directed at me that some people want me to STFU on this theme, but I won’t. The sequel to #EmpireLand is out soon. #EmpireWorld”.

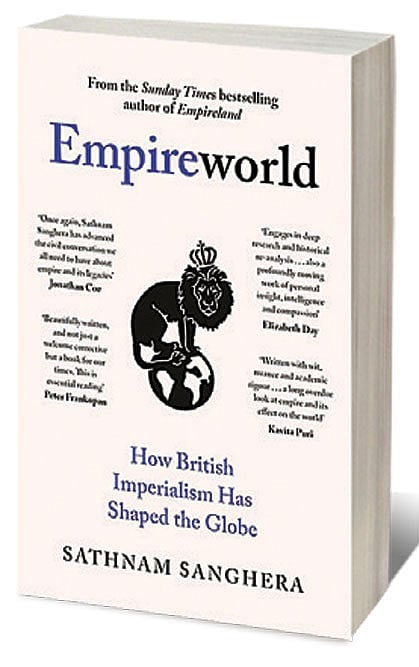

Sanghera’s latest historical book Empireworld: How British Imperialism Has Shaped the Globe (Viking; 464 pages; ₹999) has helped him see the leitmotif in his own work (a memoir The Boy with The Topknot (2008), his novel Marriage Material (2016), and then the empire books). He says, “I feel like I’ve always been a historian, but I just didn’t realise it.” His first book was about family history. So he had to find out what happened to his parents. His second book was a novel set in the British Asian community in the 1950s, ’60s, which involved its own historical research. Empireland and Empireworld are a continuation of his investment in history.

Empireworld does not need to be read in conjunction with Empireland, but it furthers his previous argument and examines the wider, global significance of British imperial power. It was also prompted in part by the abuse and trolling he received for the previous book. In the last five years, Sanghera has noticed, the theme of empire has only gained currency. Empire has been “weaponised by the right wing” he wrote in The Guardian as “Now there’s this idea that you need to be proud of imperial history to be proud of the country and vice versa. It’s become a proxy for patriotism and race.”

This climate of heightened sentiment—where ideology runs thick in the blood of the country, where every conversation is reduced to ‘with us’ or ‘against us’, where patriotism is not pride, but a war cry—is fertile ground for a book on empire. As Sanghera says, “This culture war has been good for me. It has sold me a lot of books. It’s giving me a voice. It’s giving me meaning, a purpose.”

He also feels that the interest in empire has increased because of a reckoning and a revelation. Historians and journalists are now joining the dots between what is happening in Israel and Palestine today, for example, and how “it is a problem the British helped to seed.” Also, a lot of information on empire was deliberately suppressed (the British, for example, burnt stacks of papers in Delhi on their departure) and historians are now finally catching up with what was lost.

To examine the effects of empire, Sanghera travels from Barbados to Nigeria to India to Mauritius. In chapter one of Empireworld Sanghera plays a delightful game of ‘Spot the Colonial Inheritance’ in Delhi. And lays bare the fact that so much in India—from the Western style of dressing to the English language to the post box to the game of cricket to the direction of the traffic to the wide streets to a cup of tea to Lux soap to Vaseline to diamonds—winds its way back to the British empire.

Sanghera makes the point that the attempts at decolonisation are not futile, but that they can often be tokenistic because empire is so baked into the country. Trying to remove the British empire from the fabric of the country would be as impossible as “getting the ghee out of a masala omelette”.

Speaking over Zoom, he adds, “I actually think a lot of decolonisation efforts in India and around the world are really important. They’re about rising confidence. They’re about rising historical knowledge. They’re about claiming dignity. There’s a lot of positive things.” He adds, “But the way in which Indians, at the moment, are conflating British history with Mughal history is problematic. Ultimately decolonisation is impossible.” To make his case for how ‘baked in’ empire is, he asks, “What do you do? Pakistan is arguably a creation of British empire; do you get rid of Pakistan? Do you get rid of Nigeria? Do you get rid of Nairobi? You can’t fully decolonise things. So anything you do is going to be tokenistic. But there’s real value in doing some of those things.”

EMPIREWORLD IS HELMED in the idea that history and the present cannot (and should not) be seen as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and that “opposite things can be true”. For example, it is true that some Indians have risen to the top positions of power in the world (whether it is Rishi Sunak or Satya Nadella) but it is also true that some Indians work in indentured-like circumstances as labourers in countries across the world. Studying history is a way of realising that “history is really contradictory and complicated”. For Sanghera, it is important to think beyond the “hoary old balance-sheet view of imperial history”. He finds the age-old debate about whether the British were ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for India as “ultimately nonsensical”. He says, “You can’t balance millions of lives against miles of railway. It’s utterly philosophically, logically, historically illiterate. Empire was different things in different parts of India. It varied around the empire. It varied across time. It is varied even today. So, to say, ‘Empire was one thing’ is unnuanced. It was a million different things, and we need to stop trying to balance them, and just try to understand the discrete legacies.”

Sanghera brings this similar nuance to the topic of reparations. He believes the returning of “loot” from present museums to former colonies is important, as many of these items are essential to the identity of these countries, whether it is Ghana or India. He feels the renaming of places and the embrace of one’s mother tongue can prompt a sense of pride and dignity. By revealing how imperialism inks our day-to-day life, by laying bare the brutish and often brutal nature of colonialism, which valued the lives of a few over the lives of millions, which dehumanised races, Sanghera does not wish to “incite white guilt,” instead he wishes to “promote understanding”.

But can ‘guilt’ be a useful sentiment at a national scale? He says, “Accountability and responsibility are useful things in politics, when talking about history. But in terms of history itself, history doesn’t care about your feelings. And when I say feelings, it’s not just guilt. It’s pride as well. In Britain, there’s a massive culture war and there’s a lot of people out there on the right wing of British politics who argue we should be proud of this history. And it’s absurd. It’s like saying we should be proud of the sky in India, or in Britain, saying, ‘I’m really proud of the rain in Britain.’ It’s got nothing to do with your feelings. History is an intellectual thing. And we should seek to understand this thing rather than view it through the prism of shame or pride, which is traditionally how we view history in Britain. We’ve done that for centuries and it hasn’t really got us anywhere. So, it is time for a new approach.”

Sanghera, who graduated from Christ’s College, Cambridge with a first-class degree in English Language and Literature, believes that the hoary approach of imperialists to colonialism can be best understood in the English poet Rudyard Kipling’s poem, ‘The White Man’s Burden’ (1899), where he exhorts Americans to do in the Philippines what the British have done to Indians. It is useful to revisit this egregious poem, where Kipling sees the white man as saviour, intoning, “Take up the White Man’s burden—/ Send forth the best ye breed— /Go bind your sons to exile / To serve your captives’ need; / To wait in heavy harness / On fluttered folk and wild— / Your new-caught, sullen peoples, / Half devil and half child.” The poem illustrates how while the British might be unable to see themselves as racists, “the racial science that emerged in the 19th century had a distinctly British flavour.” Sanghera says that the empire was a test area for many of the British’s weird racial theories, which continue to find resonance today, for example the idea that the Sikhs and Gurkhas are martial races, or that Indians are born to work hard.

Sanghera says that finding empire in everything from soap to racist theories has been both enriching and exhausting. In jest, he compares himself to the elderly NRI gentleman, “Mr Everything Comes from India” of the hit 1990s BBC show, about British-Indian culture, Goodness Gracious Me. (Which immediately takes me to a clip from the show where the aforementioned man proclaims that legendary Italian painter Leonardo da Vinci is “Indian” because in his painting The Last Supper there are only men. “The women are in the kitchen,” he surmises.)

Just as Sanghera is willing to see himself as “Mr Everything Comes from Britain,” he also brings a lightness of touch to his deep research. Filling the book with a chattiness, which jars at times and amuses at others. In the chapter on how horticulture has played a role in colonialism, he throws in lines, like “Those surprising botanists”.

For a reader in India, it is rather surprising that he was not previously aware that ‘ganja’ is a Hindi word or that rubber comes from plants. His sentence, “I had no idea that rubber can be a naturally occurring material. Learning that Playstations grow on trees would have been only marginally more surprising…” seems rather facetious.

To safeguard against adversaries, Sanghera has an obsessive level of footnoting in Empireworld. The book ends on page 247. The bibliography runs for 50 pages, the notes for a hundred-plus pages. “My writing method is insane,” he confesses. While each chapter is around 10,000 words, the original chapter drafts were closer to 50,000 words. Even a sentence—describing the events of India around the 2013 same-sex judgment—“In Bangalore people proudly waved the LGBT flag and set off celebratory balloons” comes with a footnote! I ask why. He says, “My editor, I think, got annoyed. I know my footnoting is quite intense, and that’s because I get trolled a lot. I have people trying to undermine me in reviews and claiming I’m not a proper historian. So, I just wanted to turn up with the receipts.”

With Empireworld Sanghera has clearly turned up with much more than the receipts, he has arrived with a palimpsest. He is also, for now, done with writing about empire, asserting, “My next book is going to have nothing to do with empire. It’s going to be about art.”