Roth Unbound

We are punished far in excess of our guilt…Yet in the very excess of suffering lies man’s claim to dignity.

—George Steiner, The Death of Tragedy (1961)

THE BIOGRAPHER’S CHALLENGE, especially when dealing with a living subject, or a subject who had been alive through most of the project, is to avoid becoming the story herself. Philip Milton Roth had never had a big biography. Part of the reason was the man himself who kept dismissing would-be biographers, even ones he had put on the job. Then came along Blake Bailey and Roth said: “I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting.” The world waited. (As did this reviewer whom Bailey had informed in private correspondence that he had just begun working on Roth’s biography.)

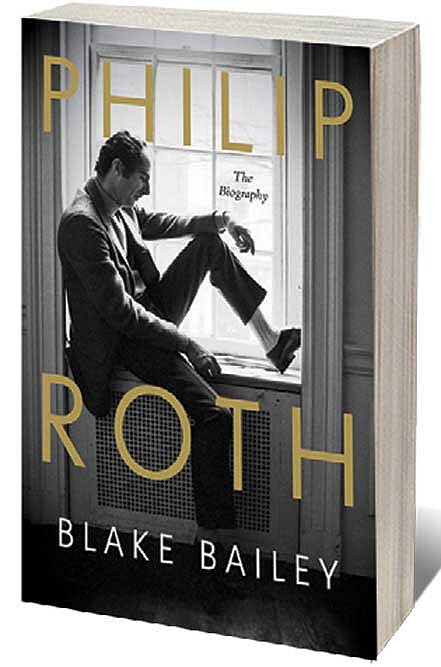

Some eight years went by. Roth died three years before publication. When the biography was ready in 2021, it was billed as the biggest book ever on the Master who had assumed the mantle of the ‘greatest living American author’ after Saul Bellow’s death in 2005. (We keep forgetting Roth is no more; or that he hasn’t said a word about the book and its aftermath. The anniversary of his death, in fact, is May 22nd.) By the time the Category 5 storm hit Bailey and Philip Roth: The Biography (WW Norton; 906 pages; Rs 3,565), the reviews had already begun incorporating a sense of disappointment. The consensus appeared to be: Bailey hasn’t endeared Roth to readers and critics who were never enamoured of him enough to instinctively look beyond his failings as a man. Rather, in cheerleading Roth through his gripes, Bailey has ended up painting him a misogynist, petty and vengeful, who never got over the consequences of his marriages to Margaret Martinson and Claire Bloom, who never forgot, and never forgave.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

As the allegations of sexual harassment—from dirty jokes with minor girl students to more recent accusations of rape of adult women—against Bailey multiplied and WW Norton decided to kill the book, the reviews got harsher. Ironically, that harshness was not altogether without reason and not exactly coloured by instant judgment on the author. It had textual vindication. (Quite a turnaround from Cynthia Ozick’s ‘narrative masterwork’ compliment.) In about 2004, when Roth’s once-close friend Ross Miller had signed a contract for a big biography, he had been warned that the book must not become ‘The Story of My Penis’. Miller had been kicked out of the project and Roth’s life because Roth soon found he could not control the narrative, given the interviews Miller was lining up. With Bailey, the story would be told just as Roth would have it. Granted full access to Roth’s papers—the whole personal archive—and, presumably, his mind, Bailey has produced an 800-plus page tome (that’s the main text), with elaborate and exquisite detail, anecdotes and rants. There is, indeed, a lot of Philip Roth in the book. But, as the critics allege, there’s a lot more of his penis.

Roth, one of the closest readers of Kafka if ever there was one, imagined Kafka laughing to himself as he spun the yarn of his nightmares. Roth would know, having attempted to ‘out-Kafka’ Kafka with The Breast (1972). Surely, he would be looking in the mirror and laughing? Or would he be plotting revenge against his biographer and/or the biographer’s critics? What we can be more certain about is that he wouldn’t be able to detach himself: ‘But Kafka escaping? It seems unlikely for one so fascinated by entrapment...’ (‘Looking at Kafka’, 1973, collected in Reading Myself and Others, 1975). Bellow’s Herzog felt himself a prisoner of his perception. Roth was in a prison of his own making by what he judged was his inability to learn from mistakes. In 2013, he wrote to Bailey: ‘High-powered people have a tendency to get carried away, to be sure, but twice [referring to his two marriages] in life, catastrophically, at the beginning and nearly approaching the end—as though I had learned NOTHING—I put the high-poweredness to the worst possible use. I didn’t flee to Bora-Bora—not me! But then 31 times [the number of his published books] I put it to proper use, to the only use that was of any use to me and I (me?) to it...’

Bailey’s nudge-and-wink trajectory with Roth is not the book’s failing—a sympathetic biographer is not an abomination in and of himself. It does lead to an understanding that—albeit a little hackneyed when the subject has had a nearly six-decade-long career—is nevertheless accurate: ‘Given the vastly different needs of his selves, Roth’s engagement with the world was bound to be incomplete, when it wasn’t positively disastrous.’

JEWISH-AMERICAN FICTION, keeping in mind all that Roth would throw at such a categorisation of him and his kind, is a landscape of the mind. Confined to the cities, primarily of the East Coast, 20th-century American writers of Jewish identity, no matter how nominal or secularised, didn’t have at their disposal the expanse of America—Henry James’ vast arena of ‘nothing’—or the physical experience of space. They were city kids, boys mostly, coming of age from the 1920s to the eve of World War II or in the immediate post-war years. Thus, unlike their WASP counterparts, or even Black writers in Harlem who could hark back to a remembered history (and journey) they may not have themselves experienced, space in Jewish-American writing became a mental geography. At the heart of this geography was a conflict, or duality, captured succinctly by Alexander Bloom: ‘They felt themselves pulled toward the center of American society, away from the edge where their parents lived. They grew ever more alienated from the world of the ghetto and from their own parents as well. No longer at home in this environment, they could not immediately find a home at the center either.’ (Prodigal Sons, 1986)

By the time Philip Roth properly arrived on the scene with, say, ‘You Can’t Tell a Man by the Song He Sings’ (published in Commentary in 1957 and collected in Goodbye, Columbus, 1959), the suburban, secular Jew was as American as anybody else and didn’t want to be anything else. But a lot of the rest did. The young writer who was denounced from the synagogues, in the press and in hate mail—‘self-hating’, ‘anti-Semitic’—for a story like ‘The Conversion of the Jews’ (1957, collected in Goodbye, Columbus) or ‘Defender of the Faith’ (1959, ibid)—and who mocked the perpetual Jewish anxiety of what the goyim would think—could also write ‘Eli, the Fanatic’ (ibid) where Eli Peck’s reborn Judaism leads to his insistence that his newborn son be circumcised.

At his funeral, Leon Botstein, the president of Bard College (Roth was buried at Bard College Cemetery), wanted to say Kaddish but desisted when reminded of the strictly secular ceremony Roth had asked for. After Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), which made Roth rich and a household name and earned him notoriety on a grand scale—to the extent he had wished he hadn’t written it—Roth was accused of opening the door to a second Holocaust. He had had a lot of fun writing Portnoy, as he would the ‘repellent’ Sabbath’s Theater almost 25 years later. And yet, while Portnoy was wrongly taken as autobiographical, the same essential truth about the decent, middle-class life of second and third-generation Jewish boys would be lost to most of America. Here was no WASP geography. Here was a mindscape. Here was no murder. Here was masturbation. These bookish boys weren’t really streetfighters and yet fought on with a streetfighter’s tenacity. Perhaps Roth identified with Kafka: “What have I in common with the Jews? I have hardly anything in common with myself...” However, it wasn’t confusion about where one came from.

Roth was extremely sensitive to that identity and the history it entailed, just as Nathan Zuckerman, in The Counterlife (1986), quickly picks up on the subtlest traces of British anti-Semitism. An anecdote offered by Bailey would illustrate the case. When his German publisher proposed an alternative title to the paperback edition of The Facts (1988), Roth threatened to ‘come after them with a GUN’. He faxed Andrew Wylie (his agent): ‘Why can’t a jew [sic] have his own title in Germany in 1994?’ The publisher replied in German, which made Roth angrier. In his invective-laden response, he asked Wylie: ‘How do I know what the [expletive] they are talking about? It’s written in that [expletive] language they so taught the world to love between 1939 and 1945...’ Instead of finding a new German publisher (in Switzerland), Wylie wanted to send them a note of admonition which Roth approved, ‘with a single provision: ‘SEND IT TO THEM IN [expletive] YIDDISH.’’

Notwithstanding the critics, Blake Bailey has written an entertaining, enjoyable and informative book. And the pleas for letting it survive and serve the needs of scholarship—while damning its author, if guilty as accused—address a debate far bigger than the book. The access Roth gave Bailey may not be granted to anyone by the Philip Roth Estate. So, when Skyhorse publishing announced on May 17th that it was picking up the book to republish it on June 15th as an ebook and audiobook, the news was not unwelcome. Bailey’s new publisher said: “While a writer’s own biography can certainly impact our interpretation and analysis of their work, the reading public must be allowed to make their own decisions about what to read...The answer to suppression of expression and ideas isn’t greater or responsive suppression, but greater public debate, which is silenced when a publisher prevents readers from reading a book and forming their opinions. A book is larger than its author; it is an addition to the often contentious public record for posterity.” Case rested?

The book comes up short on a different criterion: there is very little of what made Philip Roth a literary giant. In itemising the contracts, awards, royalties and prize money; in delineating in great detail the repartees, pathologies and parting shots; the actual writing—the words and sentences that Roth, a la EI Lonoff (The Ghost Writer, 1979), spent a lifetime turning around—has been forgotten. This is a biography of one of the greatest writers of all time with very little that’s ‘literary’ about it. About everything else pertaining to Roth, from the perspective of Roth, there is Blake Bailey...still.

Claire Bloom, unsurprisingly, is the biggest villain of the book. Next to her is the long-dead Margaret ‘Maggie’ Martinson. Bailey shows little sympathy for the women who walked in and out of Roth’s life, many often mistreated. Roth had fierce women loyalists too, both as personal friends and as critical assessors of his oeuvre. Even the once-feared ‘Ms Kakutani’s original mind’ (letter to Bellow) was the real target of Mickey Sabbath’s hatred for the Japanese. Bloom, after nearly 17 years with Roth and five years of marriage, had told her side of the story in Leaving a Doll’s House (1996). It had damaged Roth, but it is just as well that his most potent response was I Married a Communist (1998), the second of the American Trilogy that was, as Salman Rushdie called it—including The Dying Animal (2001) and The Plot against America (2004)—Roth’s ‘late blast’ that sealed his place in the history of American letters. It may matter but is of no consequence to a textual reading whether failing to condemn Roth, or appearing to condone him, is a moral failing on Bailey’s part or whether his own alleged sexual predilections have made this a book so much about Roth’s libido. He could just have spared us the details we did not need to know.

SPEAKING AT STANFORD in 1960, Roth had said: the “American writer in the middle of the 20th century has his hands full in trying to understand, describe, and then make credible much of American reality...The actuality is continually outdoing our talents...”

Fifty-two years later, when he announced he was retiring from writing, Roth told the French magazine Les Inrockuptibles: “I don’t know anything anymore about America today. I watch it on TV. But I don’t live there.” The quartet that concluded with Nemesis (2010), Roth’s last novel, was a prolonged meditation on death. The quietness and discipline that had characterised a writer who wrote standing up from the mid-1990s due to his back pain spoke for themselves. America had not defeated Roth. Perhaps he had exhausted its possibilities.

There was, above all, his kindness. He bequeathed not only generous educational funds for the wards of his friends, not forgetting his cleaning lady in New York, but chose the Newark Museum and Public Library (not a university that would have paid handsomely) as the destination for ‘the lion’s share of his estate’. The 4,000 books in his rural Connecticut home went to the special Philip Roth Personal Library Collection. That’s to say nothing of the millions of dollars. Roth, in death, returned to his beloved and blighted Newark to grant its public (and young readers) what was once the essence of an accessible library: educating people. It’s another matter that public libraries hardly serve that purpose any longer.

Tolstoy, Chekov, Zola, Ibsen, Strindberg, Joyce, Greene, Akhmatova, Borges, Nabokov...Roth. The list of Roth’s august company is actually longer. Bailey sums it up in an anecdote: ‘Toward the end of his life Roth would walk (very slowly) from his Upper West Side apartment to the Museum of Natural History and back, stopping at almost every bench along the way—including the bench on the museum grounds near a pink pillar listing American winners of the Nobel Prize.

“It’s actually quite ugly, isn’t it?” a friend observed one day.

“Yes,” Roth replied, “and it’s getting uglier by the year.”

“Why did they put it there anyway?”

Roth laughed: “To aggravate me.”’

Philip Roth thought he was punished far in excess of his guilt (or error of judgement). He will remain entitled to that opinion. But in the Hebraic worldview, there is no tragedy.

His biographer may feel the same about himself. But would we care? Especially since, he may be wrong. And he was never the story.