Romesh Gunesekera: An Island in Memory

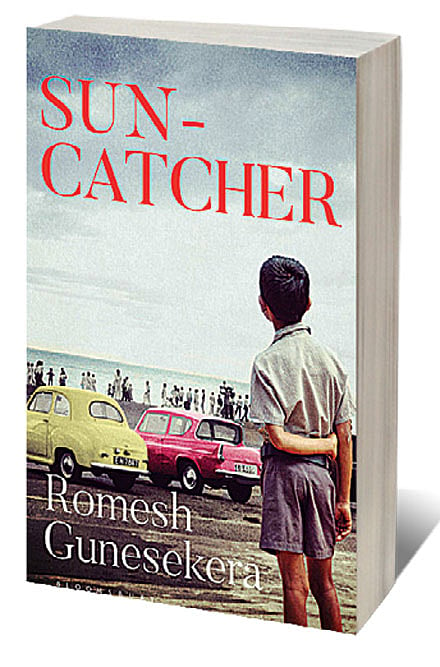

IN 1994, ROMESH Gunesekera’s debut novel Reef was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Narrated by an adult living in London, it recounted a childhood in Sri Lanka in the 1960s, when a 11-year-old Triton worked as a domestic help for a marine biologist, Mr Salgado. In his latest novel Suncatcher (Bloomsbury; 208 pages; Rs 599), Gunesekera returns once more to the foibles of youth and to the early 1960s in the country of his birth.

Suncatcher is narrated by Kairo who tells us of a summer, when he has time on his hands, and dreams that exceed his circumstances. He is the acolyte searching for a guide, who he finds in the master-of-his-own-will Jay. Set over the summer of 1964, this is a coming-of-age story about the desire for connection, and the fragile, tenuous nature of friendships, and how single summers can define the course of one’s life. It also shows us the compassion and cruelties that young boys are capable of, as they struggle to find their own footholds. Like in Reef, the troubles of Sri Lanka are dealt with at a personal level. Gunesekera masterfully demonstrates how politics is not rhetoric, rather it bleeds into and colours the lives of the characters, both in subtle and obvious ways. He deals with conflict at the level of homes and hearts and reveals how decisions made by governments affect us all in big and small ways.

Explaining the genesis of the novel, he says, “Friendships are lost. Youthful friendships, especially. And those friendships can be important. You might forget about them. And for a lot of people, they are just gone forever, but they can be formative ones. Like the first love, the first kiss. I wanted to explore that as the starting point. And then how the rest of the world, including the politics of the world, impinges on

these friendships.”

Sixty-five-year-old Gunesekera spent his early childhood in Sri Lanka, before moving to the Philippines with his parents. He describes his parents as “very unusual people. One end they were Marxist. The other end they were hosting the queen”. While he did see Sri Lanka of the 1960s through the eyes of a child, this is a novel of imagination rather than memory. He says, “I’ve used what I can remember. Whether I can trust what I can remember is a different question.” He finds that today he has no one who can verify his memories for him, as most of the people he knew at that time have died. There is no one he can turn to to fill in the gaps of his past.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

He travelled to England in the 1970s, to study at Liverpool, and has been in England ever since. Suncatcher is his eighth book. He was in Delhi recently, on a fleeting visit, to attend a literary festival. He confessed he’d spent more time at the visa office in London, and on the flight, than in Delhi itself. But his brief stint made sense given the shroud of smog that was suffocating the Capital. Despite his fatigue, evident in his tired eyes and dishevelled hair, Gunesekera was generous with his time and attention.

Why did he choose the summer of 1964 in Suncatcher? He replies, “I could have set this in 1962.

Or ’65 or ’66. I wanted it to be in the ’60s. But ’64 turns out to be quite an important, pivotal year, where things are changing.” He adds, “You have a nationalist agenda beginning. You have a socialist government, gambling and horseracing were becoming outlawed. There was a very precarious government surviving, with people crossing over. It seemed a moment of big change. And after that the whole left-wing movement changed.” It was the year when the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, a Trotskyist political party split and joined a coalition government. Gunesekera recounts how it was a time where the races had been stopped at a beautiful

racecourse in Colombo, but the betting shops continued, as people in Sri Lanka were now betting on races in England.

The reader is immersed into this place and time of change through the boys Kairo and Jay. Kairo comes from a middle-class family. His father is an armchair Trotskyite and a senior executive to the Labour Department, and his mother works at Radio Ceylon. Jay on the other hand belongs to a wealthy family, resides in Casa Lihiniya and spends his time tending to fish and birds, cars and guns.

Through the eyes of Kairo, Gunesekera conjures the contrast between the worlds of the boys. Kairo says of his own parents, ‘Sadly, both thrashed around in the same hole making do—nothing more. A hole I knew I had to escape from. If only I could have spent my whole life in Jay’s house; a place full of mystery where the adults, like his fish, floated in a diaphanous ether, where you made the world in the shape you wanted it to be...’

The relationship between the boys is essentially one of leader and follower. Kairo wants to be part of Jay’s world, a world full of possibility and potential, where parents bestow and don’t hover, giving Jay a freedom that only affluence can allow. But wealth brings with it its own demons, and Kairo realises that his parents give him a sense of security that Jay’s parents are incapable of providing their son.

Kairo is thrown into fits of insecurity when he fears that Jay might have found a girlfriend. For Kairo, Jay is an escape chute out of loneliness. Gunesekera wonderfully evokes the unequal relationship with sharp insight and detail. As the narrator Kairo says in Suncatcher, ‘At the roundabout, I stopped. The roads were empty. I had not seen the girl who’d ridden with Jay since that day by Independence Hall but he had, no doubt, and it troubled me more than I could understand then. If only I could hold Jay back from stepping out of our world—my world—into that adult world that seemed so full of recrimination and regret. A world so messed up that it mistook death for the love of God.’

Talking about the dynamics between the boys, Gunesekera says, “I had a Jay friend. But the reason for the book is that we all have a friend like Jay. And if we haven’t had a friend like Jay, we’ve always wanted a friend like Jay. And we’ve been looking for a friend like Jay. I’ve always been wanting to write about friendship at that age. This novel is much more about the loss of friendship than anything else. And the ebb and flow of it, that is something that has always interested me.”

We all want a friend who expands our horizons, someone who removes us from our comfort zone and takes us to worlds that are so different that they dally with danger. But if we want that friend, unknowingly we are also that friend to someone else. Gunesekera says, “When I was young, I desperately wanted to be Jay. Like Kairo wants to be Jay. But I am sure, unknown to me, I was Jay to somebody else.” He recounts with a warm chuckle how he once got a hint of this during a reading in England, when a retired doctor came up to him and said that while he might not remember him, he was in his class in Colombo. The doctor then told him, “I remember the watch you wore. You used to wear a different watch strap every week!” Gunesekera realised that the man was talking of a watch that he had himself forgotten, which the captain of a ship had given him with changeable straps of different colours. If he wanted a Jay friend as a boy, he was a Jay to someone else as well.

LIKE KAIRO, GUNESEKERA grew up in an English-speaking household. In countries like India and Sri Lanka, language has always been a most potent instrument for inclusion and exclusion. The Sinhala Only Act or the Official Language Act was passed in the Parliament of Ceylon in 1956. The Act made Sinhala the official language, replacing English. In Kairo’s household we see this tussle between languages play out, with the wife urging her unwilling husband to learn Sinhala. She tells him, ‘Maybe you should get some tuition too, Clarence. They won’t take excuses forever, you know. All government servants have to pass the national language proficiency test.’ The shift from English to Sinhala did vex Gunesekera’s parent’s generation, many of whom had been educated in English.

Gunesekera is well attuned to the politics of language. When he was a child in Colombo, each school had three streams: English, Sinhala and Tamil. He was in the Sinhala stream and recalls that he had minimal connection with the other streams. These silos, naturally, divide rather than integrate communities. He says, “The language question is obviously fundamental to Sri Lanka politics. And was at the heart of a lot of problems and continues to be. Language issues can divide. That is why it is a gift for politicians. That is why it is quite a poisonous gift, it leads to all these other things.”

Gunesekera’s previous book, Noontide Toll, was published in 2014 and once again chronicled the simmering tensions of his birth country. Shehan Karunatilaka, author of Chinaman, wrote in the Guardian, ‘Noontide Toll comes from the same wellspring as Gunesekera’s early work, the Booker-shortlisted Reef and the underrated Monkfish Moon. In all three books, simple stories told in delicate prose reveal curious insights, powerful ideas and painful losses… The book is an elegant balancing act and a pleasure to read. His snapshots capture the island’s terrors and its treasures, and give you an insider view of the many outsiders drawn to this troubled nation.’

While Gunesekera has been based in the UK for many decades, he still calls Sri Lanka “the place of my imagination” and writes of it like an insider. He spent more than four years on Suncatcher and wrote some of it in England, some in Sri Lanka and some even in Singapore. In his subject matter, he finds that he keeps returning to Sri Lanka. He says, “I just like the characters that emerge. I just like their company. I like being in that imaginative space.”

In 2013, Gunesekera wrote a new introduction to Reef, describing the novel as ‘a story of memory and imagination in a country on the brink of change’. In Suncatcher he returns to the trope he knows best by telling us the story of a boy growing up and trying to find his place in a messy world.