Ravi Shankar: The Hermit and the Heartbreaker

OLIVER CRASKE WAS only 23 when he met Pandit Ravi Shankar for the first time in 1994. He was to help the 74-year-old sitarist put together his autobiography, Raga Mala, and at that meeting, Craske was nervous. Speaking on the phone from London, Craske says, “He did his best to put me to ease. You sensed he was very erudite about music but not in an intimidating way. He welcomed you in.” Sitting down on a sofa with Shankar, Craske was struck by the musician’s knowledge and experience, but also by his personality. “He had an aura that made you want to spend time with him.”

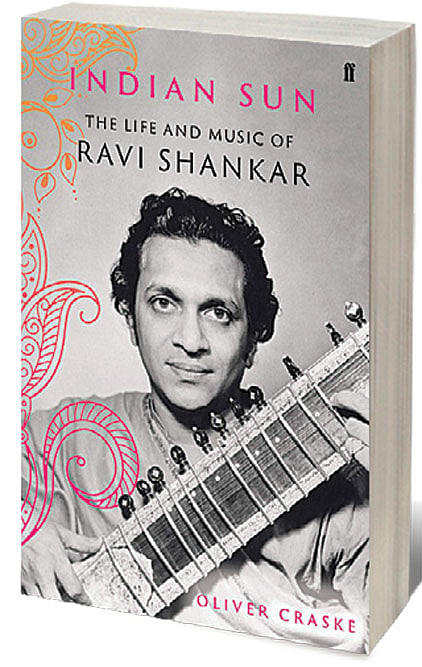

Their relationship endured, lasting until Shankar’s death in 2012. Shankar would regularly update Craske on the developments of his life, encouraging him to assume the role of a future biographer. The recently released Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar (Faber & Faber; 672 pages; Rs 799) sees Craske deftly make use of the confidences he had been trusted with. But helping the book exceed the biases of Shankar and his inner circle, Craske relied on a repository of another 130 interviews when writing Shankar’s first biography. Even though Craske confesses he “was awestruck by [Shankar’s] prodigious musicality”, he seldom venerates his subject. He doesn’t use the epithet ‘ji’ for Shankar. He refers to him as ‘Ravi’.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Indian Sun is more than a sum of colourful anecdotes. It balances personal history with evidence of Shankar’s musical mastery. Craske writes about Hindustani classical music lucidly, never alienating the uninitiated. He explains the structure of raga and the cycles of tala with an acuity that is always accessible. “I wasn’t his formal disciple, but if you were with [Shankar], he would want you to understand the music,” says Craske. “He was a great teacher and proselytiser for music. I would say that I’ve learnt from the best.”

The list of Shankar’s Western pupils is long. It boasts of names such as George Harrison, Philip Glass, Yehudi Menuhin and John Coltrane. The West, it’s clear, reciprocated Shankar’s embrace, but his detractors in India only multiplied. The charges against Shankar were severe. Accused of having polluted Indian music, Shankar was caught between his devotion to tradition and the pressures of modernity. Craske writes in his introduction, ‘While his fame remains unrivalled among Indian classical musicians, he is sometimes underestimated as an artist […] Surely, he must have sold out?’ As a biographer, Craske rarely ever lets adoration iron messy creases. He sees Shankar as both insider and outsider. As he puts it, ‘We often describe people in terms of opposites. They can, of course, be complementary qualities.’

Having read Indian Sun, you feel compelled to believe Craske when he says Shankar lived “one of the great lives of the century”. In the 1930s, for instance, Shankar was touring the world as part of his brother Uday Shankar’s dance troupe. Only a child at the time, he perhaps didn’t feel history’s weight when in 1932, he saw swastikas brandished in Germany during Hitler’s parliamentary campaign, or when he found himself at New York’s historic Cotton Club at the height of Prohibition. “But he could say ‘I was there’ when these historical episodes were referred to. He crops up in all these extraordinary places,” says Craske. In India, he sang for Mahatma Gandhi and was blessed by Rabindranath Tagore.

Travelling with his elder brother had left an adolescent Shankar with an ‘understanding of how Indian performing arts could be successfully presented abroad’, but more significantly, it was during these international tours that he came to know his guru, Ustad Allauddin Khan, or ‘Baba’, as the ascetic disciplinarian was affectionately called. In one of Indian Sun’s more light-hearted moments, we see Shankar shooing away a nude cabaret dancer from Baba’s lap, saying, “He’s a priest, celibate—please move.” Shankar later took Baba to Notre-Dame and saw the cathedral move his future master to tears.

Shankar had spent seven-and-a-half years with Uday, and he came to spend approximately the same amount of time studying with Baba in Maihar, Madhya Pradesh. Shankar’s life couldn’t have changed more dramatically. The transition from dandy sophisticate to devoted disciple required a toil that was wholly new. There were days when Shankar’s riyaz lasted 16 hours. Baba was known for his quick temper, but in all his years at Maihar, Shankar was rebuked only once. “Go and buy some bangles to wear on your wrists. You are like a weak little girl,” Baba scolded him. Shankar left with his bags, but was pacified by Baba’s son, future sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan. “The relationship had its difficult points, but Ravi was devoted to his guru. He spent a lot of his career singing his praises,” says Craske.

The musicianship Shankar received as an inheritance from Baba was marked by an abundance that was immediately conspicuous to those listening to him on the radio or in concert halls. What bothered Shankar were comments and reviews less effusive. “He was a sensitive person, and he found criticism hard to take,” says Craske. Shankar’s score for Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy enchanted many, but Craske writes that ‘over the years there were occasional public hints of underlying friction between these two giants of Bengali culture’. Speaking to Open, the biographer ascribes this tension to both personality and popularity: “Ray had once talked about Ravi Shankar’s drawbacks as a film composer, and I think that sort of thing would upset Ravi. This had something to do with his sensitive personality, yes, but you also cannot underestimate the pressures of popularity that can sometimes be unhealthy.”

The rivalry between Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Vilayat Khan is now the stuff of Hindustani classical legend. In 1952, when the sitarists took the stage together, Khan played a particularly difficult taan that Shankar couldn’t replicate. The papers claimed Shankar couldn’t keep up. “Even though there was an unpleasant tinge to the episode, there’s also something quite funny about it,” says Craske. “It was an ambush. They became terribly obsessed with each other at that point.” When Shankar began taking the West by storm, Khan said he had diluted Indian classic music. As news of Shankar’s friendship with George Harrison started to spread, Khan prefaced his concerts with the jibe, “This is not [a] Beatle sitar, this is the real sitar.” As Shankar wrote at the time, ‘It was like Salieri with Mozart.’

After hearing Shankar play abroad, Pandit Shivkumar Sharma once clarified that the music he played to Western audiences was “pure classical”, but Indian Sun goes beyond such endorsements when demonstrating its subject’s steadfast commitment to the Indian tradition. Shankar’s first sitar lesson to Harrison, writes Craske, was interrupted by a phone call. As the Beatle went to step over his sitar, Shankar slapped him on the leg and said, “The first thing you must realise is that you must have respect for the instrument.” Craske points out that in the early 1960s, Shankar felt an aversion to “superficial” Western pop music, but seeing Harrison’s sincere love for Indian classical music, he changed his mind.

In 1967, having stolen the show at the Monterey Pop Festival and released 12 records in the US, Billboard declared Shankar its Artist of the Year. That year, Shankar performed at the UN General Assembly with violinist Yehudi Menuhin and to top things off, “John Coltrane had named his son Ravi, the Doors were attending his music school.” Based on the evidence that Craske provides, it seems Shankar wasn’t co-opted by the zeitgeist, he instead defined it. “If you notice, he didn’t go jam with the rock and pop musicians he met, nor did he try and play western music. He was a kind of missionary, I feel. He really wanted to enlighten the rest of the world with Indian music,” says Craske.

In 1997, The Times of India published a profile of Ravi Shankar with the headline, ‘The Sun That Rose in the West’. Craske takes issue with this assertion. “He rose in the East,” he insists. “That later global fame has rather come to dominate his reputation, but I think it is important for India to remember what was going on before and why he was in a position to do what he did.” Working for All India Radio in the 1950s, Shankar gave several of his colleagues a platform they might have otherwise been denied. “At that point, Indian classical music was bursting out from its 19th century courtly scenario and reaching all corners of the country. As both musician and gatekeeper, Ravi enabled this.”

Indian Sun, one might argue, earns some of its authority by blurring the hard lines that separate private and public personas. For Craske, it seems, Shankar’s personal relationships are as vital as his musical talents. His book doesn’t just tell us about all that Shankar did, but it goes a step further by describing how he felt. Speaking about the effects of Shankar’s childhood abuse, for instance, Craske says, “He spoke of this sense of loneliness he had ever since his childhood, and in the book, I conclude that this had something to do with his early traumas. You see it in his behaviour but also in his music.”

Shankar’s inability to stay put in one place also led to what he called a “butterfly lifestyle”. Despite being married, he went on to have many girlfriends, nearly 180 of them. Most of these relationships were ‘all passion, no commitment’. Much like his own father, Shankar remained largely absent for his first child Shubho. “Ravi once said to me, ‘I’ve never been a good father, but I didn’t know what it means to be one. I never had one.’ I think some may find his relationships awkward, especially his role as absentee father,” says Craske.

Anoushka Shankar was seven when Shankar married her mother, Sukanya. In Craske’s interviews with Anoushka, she speaks at length about the strong, loving bond she forged with her father in the years that followed. Shankar’s relationship with his other daughter, singer-songwriter Norah Jones, was more complicated. She tells Craske, “When I first got reunited with him I was 18, and I was kind of angry. I was like, ‘Where have you been?’” Craske says that Jones’ subsequent stardom came with its own pressures, “but they worked that out. When writers like us are writing about these relationships, it becomes difficult to work them out in private. Ultimately, despite the bumps, it was a happy story”.

Those looking at Shankar’s life have sometimes found it hard to reconcile his rigour and proclivities. How could a heartbreaker also be a hermit? According to Craske, “He might sound like someone who is undisciplined, but in truth, there was a terrible discipline about his life and his music. He would always turn up on time. He would always play the show.” In public and in private, Shankar lived many lives, but his first biographer feels that music remained a common core: “When he was playing live, an alap perhaps, he was completely in the moment. His music became his way of accessing feeling.”