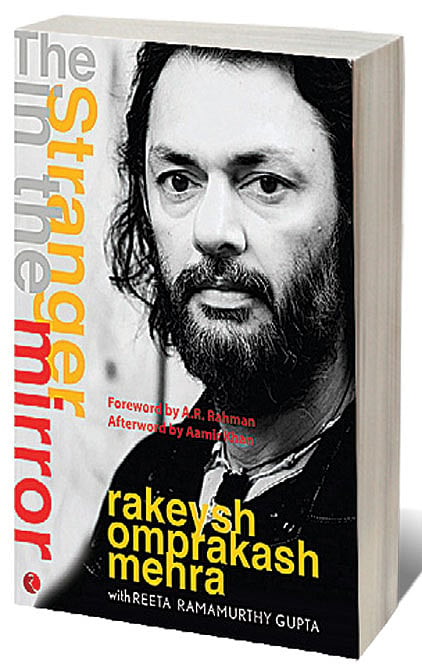

Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra: ‘Films Are Like Your Best Friends’

FILMMAKER HAS TO be a soothsayer, to ensure the story he is telling now is still relevant a year or two years later when the movie is released. He has to be a magician, so audiences can enjoy the tale, without agonising over the process. He has to be a social anthropologist, so he can correctly interpret the world for others. But more than anything else, he has to be a truthteller. He has to tell the story truest to himself at that particular point in his life, the life of his nation, and even the world.

For Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, 58, who made his cinematic debut with Aks in 2001, movies are the mirror he holds up to society so it can see itself for what it is. It isn’t always pretty. But he doesn’t believe in averting his gaze. Rather, he will swoop in for a close-up, framing every wart, every flaw, every wrinkle, with care, attention and detail. His successes are magnificent, and his failures even more so. That makes him truly unique. If Rang De Basanti (2006) became the anthem of a generation that wanted to overthrow a corrupt system (it’s another matter that it was replaced by another that was equally amoral), Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013) was a sports biopic that tried to heal deep wounds and offer a soothing balm.

That is Mehra’s modus operandi. Ask him about his new movie, Toofan, a boxing epic starring Farhan Akhtar, and he says he wanted to make a soothing balm for a society that is clearly at odds with itself. This is the leitmotif of his life, and it’s beautifully captured in his autobiography, The Stranger in the Mirror (Rupa; 340 pages; Rs 595). Starting from a childhood spent in the staff quarters of Claridge’s Hotel in Lutyen’s Delhi, Mehra had an early taste of what it is to be the outsider, to be able to see, but not always touch, his nose perennially pushed up against the windowpane of another life, a posh life, a life he didn’t have. A child of pre-liberalisation India, Mehra knows what it’s like to live with less and yet be happy. It is hardwired in his DNA, and it’s probably the reason he is so unafraid of failure. Those who begin life with nothing but their talent are usually unafraid of returning to that place of not having anything, it gives them permission to take big leaps in imagination and in execution.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Mehra says after making the indie film Mere Pyare Prime Minister in 2018, he felt he was at the interval of his film career. “I thought let me write it all down before old age gets to me,” he says, with a laugh, speaking from his country home built near Pawna Lake, two hours from Mumbai. He’s been here for the past 16 months and loves the isolation it offers. “The journey so far is so vivid in my thoughts and memories. With everything you have achieved, you tend to give yourself the credit, but it is such a combination of the universe conspiring to make things happen and your parents bringing you up in a certain way,” he says.

The Stranger in the Mirror gives us the life of an artist. Sometimes it so dark that alcohol is the only recourse—as it was for Mehra after the failure of Delhi-6 (2009)—which confused his children and alienated his friends. And sometimes it is so heady that it takes him to places he could never imagine—to international film festivals, to hushed boardrooms with the brightest of minds, to colleges where students believe in his vision, and more importantly to studio floors where workshops crystallise into memorable movies.

Mehra has a fine sense of the history of cinema, of politics, and of life. He distils all of that into his autobiography, written with Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta. It gives us an unusual peek into the mind of an auteur, from the spark of an idea to its eventual implementation. The book takes us from the long nights fuelled by biryani at AR Rahman’s Chennai music studio to long days recreating Old Delhi in a deserted village in Rajasthan. It moves us seamlessly from a 21-day workshop with Syd Field (the American author who wrote several books on screenwriting) in Los Angeles to a quick flight to the US hoping to convince Shah Rukh Khan to take the part that eventually went to R Madhavan in Rang De Basanti. It makes us wait, with him, for the finance for Rang De Basanti to come through—it finally does through yet another outsider, Ronnie Screwvala.

Like on his films, the director has help from the best in the business, with his sometime-team members turning up in cameos to add their own voices to the story. So Gulzar tells us how Mehra is the eternal adolescent who doesn’t want to grow up. Manoj Bajpayee reminds us he is first of the cohort that emerged from the rebellion against formula cinema in the ’80s and ’90s led by Shekhar Kapur (Masoom, Mr. India, Bandit Queen), Ram Gopal Varma (Rangeela, Satya) and Mani Ratnam (Roja, Bombay, Dil Se). He, along with Vishal Bhardwaj and Rajkumar Hirani, had the courage to experiment on the path laid by these three directors, he adds. Farhan Akhtar, the star of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag and Toofan, says: “Our energies are quite different. Rakeysh is calm: even when he gets angry on set or decides to take charge because something is not happening the way it should, he conveys it without yelling. He doesn’t rush me. On the contrary, I am impatient and raring to go.”

Outstanding triumphs also mean spectacular failures, which “makes you go back to your instincts, rather than listen to the noise around you,” Mehra tells me. It has happened to him on several occasions. Aks, an ambitious story of Ram versus Ravana, good versus evil, and how sometimes it is impossible to tell them apart, was critically acclaimed but commercially a disaster. Delhi-6, a sweeping tale about the hatred inside us, embodied by a black monkey terrorising the neighbourhood of Old Delhi, once a paragon of communal togetherness, failed but not before becoming the director’s favourite film, and that of several others who saw in it an anguished cry against the blind faith tearing families and friends apart. And if Mirzya (2016), a three-layered story around legendary star-crossed lovers Mirza and Sahiban, seemed self-indulgent to the point of excess, it also gave us lead characters who could do unheroic things.

Prahlad Kakkar, an ad filmmaker who was Mehra’s mentor, attributes this fearlessness to his status as an outsider. “Outsiders have struggled for several years before getting accepted. Outsiders have the will to experiment; they understand hunger, not privilege,” he says. That insouciance is unique to them. Only they know life outside the fishbowl so they can return to it with ease. There are heartbreaks as well. Mehra once entered a theatre, one week after the release of Aks in Jaipur, only to find only half a dozen people in the theatre. A film he cherished and which was to be Abhishek Bachchan’s debut, Samjhauta Express, never got made. There were shots that were taken—even though it took transplanting an entire mustard field to create the perfect ending for Rang De Basanti. And there were shots that were not, which were added later, as to the Venice film festival cut of Delhi-6.

But Mehra is also introspective about his failures: “Why do films work? Why don’t they? The entire family takes the brunt of a flop, and yet, I want to keep experimenting. Keep trying to reach where I have not been before. Am I hurting the people I love the most? Wasn’t that what Mirzya was all about: the question I was trying to answer through the movie itself? Yet I couldn’t recreate popular folklore for my audiences. For me to turn around and say, ‘the audience didn’t understand’ is a poor excuse. It’s my greatest karma as a filmmaker to engage the audience.”

Mehra says to me that he feels drawn to films that talk about social change. “I keep prodding at it. Films are like your best friends, there has to be a connect somewhere, things that bother you and trouble you. Once you complete them, they make you feel lighter,” he says. And does he look over his shoulder when he addresses issues like love jihad in Toofan or peace with Pakistan in Bhaag Milkha Bhaag? “When you say something without an agenda or enmity against anyone else’s ideology no matter the caste, religion, colour; when you say it from a position of love, you need not be unduly worried.”

His next venture will most probably be a period film on Karna, a mythological character he has been obsessed by, for the recognition that was denied to him, and which he rages against. Again, it’s an outsider’s tale. No matter the Pali Hill home and the Pawna village office, Mehra will always remain that little boy who coloured his canvas shoes with chalk for school and now tries to over-compensate with 25 pairs of sneakers. We are who we were and Mehra’s films come from that deepest part of him, which he has explored in The Stranger in the Mirror. Mehra is a man of few words, writes Screwvala in the book, not exactly the perfect fit for the podium. This book more than makes up for that lack.