Raising Them Right

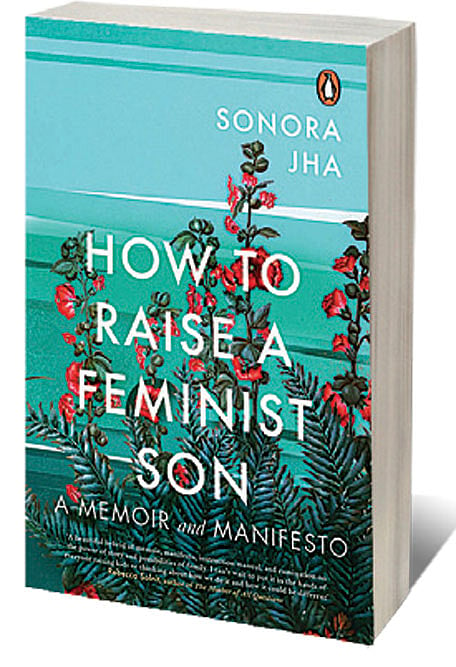

MOVIES IMITATE LIFE by depicting realities at times, and by exacerbating them at others. The young film critic mother developed her own feminist imaginations as she watched movies with her baby boy in her lap. How to Raise a Feminist Son: A Memoir and Manifesto by Sonora Jha is a fascinating book that lives up to the expectations raised by its title. It is deeply personal and simultaneously scholarly.

The rampant misogyny in films resembles her lived realities in India and in north America. Every parent is entitled to their own imagination of how she wants to raise her boy (or girl). She is free to raise her boy without toxic masculinity or gender binaries leaving him free to experience and express his own spectrum of emotions. She can raise him where he can be permitted to be wrong sometimes. He can be permitted “to fail, to fall, to cry, to be protected rather than always be protector, to be provided for rather than always be provider, to seek and receive wise counsel … to get schooled and to get laid.” This can be an onerous task where the parent can forever be in doubt internally, psychologically and theoretically. And the greatest challenge can be about how to overcome the patriarchal tendencies deeply hidden within her feminist self! The incessant reflection and iteration can make the mothering journey pleasurable. Raising a good feminist man and sending him out into the world can be the truest pilgrimage for her.

The insights in the book seamlessly emerge from a variety of sources that include dissecting religious and cultural traditions as much as academic research. The author is mindful of the fragility and the inherent challenge in her decision. There is a price for trying to question what for ages has been a “man’s place” in the world. Her feminist commitment helps her beat the accepted norms in a faraway land with practically nobody to call her own. Nor is she blind to the fellow immigrant mothers in Seattle and elsewhere in the US feeding their boys “fresh, rich Indian meals by keeping myself organized in the cycle of fermenting, grinding, kneading, steaming, marinating, spicing, frying, saucing, and garnishing the shit out of my life.” Like goddesses Sita and Parvati, she teaches her son to be loyal and to stay by her side; she teaches him to believe women, to understand that like men, women too have a will and their consent is important and non-negotiable. She succeeds in reimagining her own family and constructing her own village where she appoints new elders, new advisors, new uncles and aunts, new cousins and companions for her son to love and be loved.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

The book recognises the reality of intersectionality such as race, religion, class and caste for the victims of patriarchy. It carries elaborate material about the connections between race, gender and patriarchal norms and practices. There is a well thought out and detailed to -do list at the end of every chapter for those fellow parents who imagine a feminist future for their child. Insights are drawn from discussions with scholars and practitioners who have all imagined and attempted to construct feminist environs.

The book is easy to read even as it contains such significant content for parents and for future generations. The work is marked by a candour which is rare in the way the author lays her life threadbare for the reader to see and make the connections with different feminist principles. Not many authors of South Asian origin may be willing to discuss their personal lives for the purpose of elaborating and propounding a school of thought. Jha must be congratulated for her courage. Her vision of a boy in every man begging to be raised right is a compelling vision. If only we raise our boys and girls without preconceived gender notions, if we raise our boys to cry their hearts out as men in public, that would be love.