Questions of Belonging

Towards the end of the book The Deoliwallahs, referencing the detention camps of Assam, the callous Foreigners tribunals, and the Citizenship Amendment Bill (now an Act), the author asks a question: ‘What does any of it have to do with Deoli incarceration?’ ‘We don’t realize it’, the author states, ‘but this is what Deoli has done to us’. ‘In every hateful stereotype expressed about one or the other community today, every murderous attack on members of a different religion, every call to go to Pakistan, every unthinking use of words like chinki and kalya, you can trace the roots that stretch back a century to that prison camp.’ In Deoli’s unacknowledged history of incarceration, is a vocabulary of prejudice that has taught us to discriminate between different genealogies of descent: one worthy of citizenship and the other not.

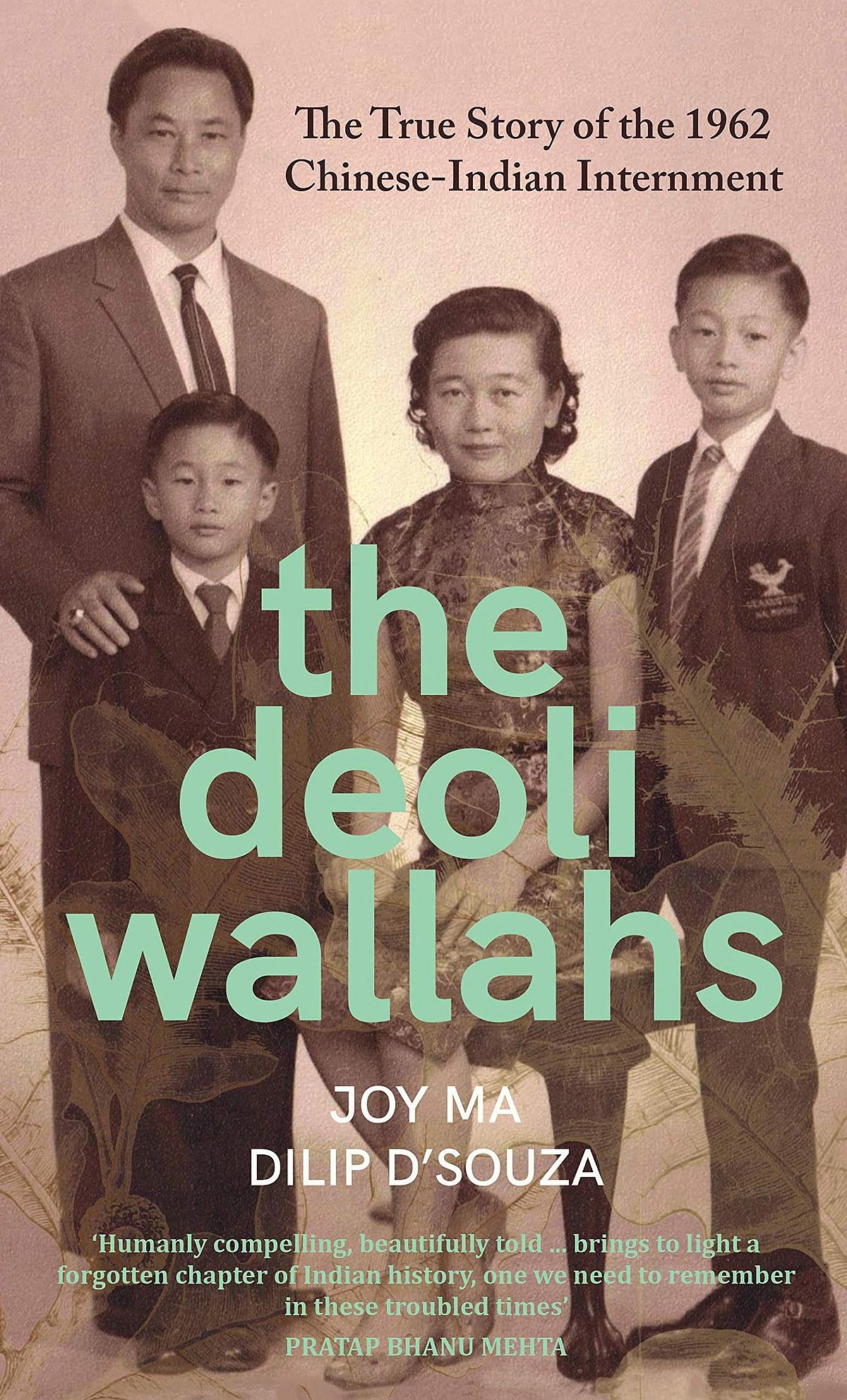

The Deoliwallahs is the forgotten story of internment of Chinese Indians that began in the aftermath of India’s debacle in the Indo-Chinese war of 1962. Indians of Chinese origins quite suddenly became targets of suspicion and distrust. Suspicions turned into official policy and beginning November 1962, the Indian government incarcerated nearly three thousand Chinese-Indians from places like Darjeeling, Kalingpong, Makum, Tinsukhia, Dibrugarh, Digboy, Nagaon etc. and sent them to a detention camp in Deoli-Rajasthan.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Authors Dilip D Souza and Joy Ma poignantly chronicle the pain and waste of many people’s many years in the Deoli camp. A labour of love, conviction and personal histories, this book is an archeological exercise of many proportions. For Deoli survivor Joy Ma, who was born to Effa and Jack Ma in the camp, it meant breaking free from the shackles of silence and ‘peeling away the layers of repressed memories’. For Dilip D’ Souza, a professional writer and an ‘aware citizen’ of this country, it meant bringing to attention a forgotten taint of our history. ‘What choice but speak up and demand a nation’s attention’, he asks? Together both authors restore, to each of their protagonists their voice as also their lived history.

Deoliwallahs documents testimonies of incarceration and internment of Deoli survivors, many of who moved to the US and Canada after release from Deoli, escaping uncertain futures and questionable citizenship. It brings together many stories such as: of Ying Sheng Wong, who remembers his train (to Deoli) compartment etched with the words ‘Enemy Train’ at which stones were hurled. Of Andy Heish who along with other ‘Chinese boys’ were picked from their school and got separated form their parents, and who recounts the years of idleness and hopelessness from 1962-1966. Of Steven Wan whose father was punished and put in solitary confinement for hiding undeclared money. Of Michael Cheng’s father, owner of the Orient Restaurant before Deoli, who lost all confidence post internment and ‘never regained that dignity because the ordeal ruined him’. Of children whose years were wasted with no schooling at Deoli camp. Of disease and sickness and death at the Camp. Of travel and residence permits needed on release (from the Camp), of erstwhile homes ransacked, encroached upon, of livelihoods destroyed and futures stripped away. And finally, of a belonging to a place—to a country, as a citizen—that was taken away, by a mere sleight of law.

This book is their history and their memory, as also perhaps their collective catharsis. But the book’s ambition is also to ask a larger question: ‘Should the question of citizenship become an embodiment of [our] deepest prejudices?’ The Deoliwallahs is an imploring reminder that the journey from being a citizen to a ‘foreigner’, from ‘insider’ to an ‘outsider’ is a short one. It could be the Foreigners Act, Foreigners Law Act of 1962 that made Chinese Indians ‘foreigners’ in their own land (even when the law did not specify or spell out ‘people of Chinese origin’). It could be the Citizenship Amendment Act today; it could be another law tomorrow. Law and its targets can be arbitrary and unsparing. Who better to tell the story than the Deoliwallahs.