The Principled Life of Kobad Ghandy

To say facts are stranger than fiction is cliched, yet not to use that phrase to describe Kobad Ghandy’s life is linguistic rigidity that deserves no mercy. Son of rich Mumbai-based Parsi parents, he attended The Doon School in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, where his classmates included Sanjay Gandhi, Kamal Nath and Naveen Patnaik. Later, he went to London to study chartered accountancy, following in the footsteps of his father and friends. But then, Ghandy did not remain in the mould he was cast in, unlike other such scions.

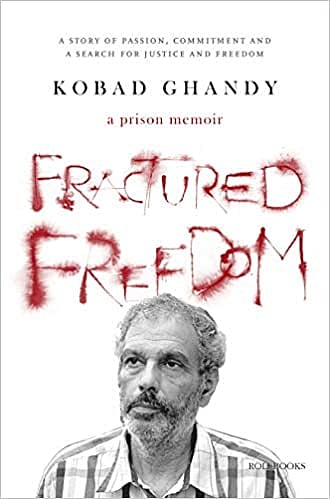

His prison memoir Fractured Freedom is more than the story of the ideology that influenced him in London. It is a portrait of an angry man who rebelled and fought for other people’s freedom. This autobiographical account lays bare the trajectory of his life: a 1947-born child who got dropped to Bombay’s St Mary’s School in his parents’ car and went for swimming lessons at the elite Willingdon Club; an all-rounder at Doon; a promising chemistry student at St Xavier’s College, Mumbai; an articled clerk and an aspiring CA in the UK who was a favourite of his employer Jackson and Pixley; a young man who refused to cower before white racists and preached to a judge of colonial Britain’s evils, only to land in a UK jail aged 24; a nationalist with sympathies for Gandhi; a Marxist who veered gradually towards Maoism and returned to India to champion the cause of the Dalits.

Several years before Ghandy, now 74, became an undertrial and was exonerated, he had acquired a stature among his comrades, who, like himself, believed in a vigorous response to society’s ills. He along with his departed wife Anuradha—to whom this book is dedicated— came to be considered icons. More so because they had abandoned a life of privilege to work for the dispossessed. His father was a finance director at the pharmaceutical giant Glaxo. He describes his mother, hailing from a wealthy family of liquor tycoons, as a ‘society lady’, notwithstanding his love for her for backing his social activism of the dangerous kind. Ishaat Hussain, former finance chief of the Tata group, is quoted in the book as saying that Ghandy, his buddy from Doon and London, was, like him, ‘ideally suited’ to become a successful CA. After their meeting in London in the late 1960s, Hussain and Ghandy met 50 years later in November 2019 upon Ghandy’s release from prison. He had been kidnapped in September 2009 in Delhi by officers from Andhra Pradesh who illegally detained him for three days before he was produced before a court and served a term of 10 years. The early part of the book covers how he became a communist, iconic bookstores of the time and a handful of authors who influenced him.

He also narrates the experience of working with the Progressive Youth Movement, which was linked to the Naxalites. It was during this period that he met Anuradha, then a student leader at Elphinstone College in Mumbai, a hub of radical thoughts and Naxalite influence in the early 1970s. The book covers the sway of the Dalit Panthers movement in Bombay and Ghandy’s own work in Mayanagar among the Dalit community as well as activities related to students, theatre and workers. He also dwells on his days during Emergency, his marriage and then the decision in 1982 to shift to Nagpur where he felt workers and Dalits bore the brunt of the mining mafia and corporates.

The key highlights of the books are, of course, his prison memories; accusations of being a ‘Maoist’ mastermind; his meetings with the likes of Afzal Guru and various dons; and the comparison of facilities and freedom at various prisons he had been held at until his release in 2019, such as Tihar where he served most of his time, Hyderabad, Jharkhand jails and Patiala. His reflections on life, religion, people, hopes and correspondence from jail with Doon friend Gautam Vohra and anecdotes from inside and outside jail make this reading experience akin to an invigorating chat with an evolved soul, and not a gauche caviar.