Power and Pelf

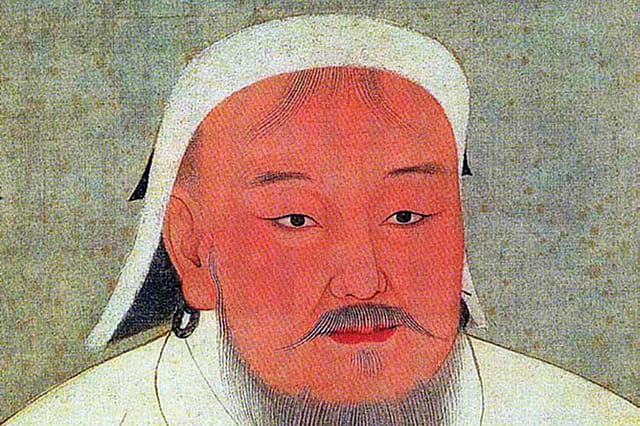

FOR A LIVELY writer who pulls unexpected rabbits out of history's hat, Jeffrey E Garten has been very remiss. There's nary a mention in his erudite, informative and readable book of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, 'the world is one family', the Sanskrit phrase from the Maha Upanishad that proves that among their many other achievements, the ancient Hindus also invented globalisation. However, he makes amends by including the twelfth century Mongol chief, Genghiz Khan, who burnt and slaughtered his way across Asia's blazing heartland, as one of globalisation's founders. Since Genghiz was a shamanist, the likes of Adityanath can happily envelop him in Hinduism's welcoming embrace. Since he was also Babur's tenth great- grandfather, a little posthumous ghar wapsi will ensure that far from being an Islamic invader, the first Mughal was a Hindu returning home.

This book bristles with other surprises. The From Silk to Silicon title carries a whiff of China's One Belt One Road project which India has righteously snubbed. The very different narrative suggested by the sub-heading about Ten Extraordinary Lives holds further revelations. Genghiz is okay since his descendants became Indian, meaning Hindu, but Robert Clive who enriched English with the telltale word 'loot' can hardly have looked beyond imperial frontiers except to survey further territory to seize. As Shashi Tharoor says, "The British had the gall to call him 'Clive of India', as if he belonged to the country, when all he really did was to ensure that a good portion of the country belonged to him." An English globalist is a contradiction in terms; witness the Englishman who marched up to an official at a port with two doors marked 'Natives' and 'Foreigners' and demanded, 'Where do I go?' For that matter, Mayer Amschel Rothschild, 'the godfather of global banking', lived and died in a Frankfurt ghetto.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

It doesn't seem to add up. But Garten explains his nine men and one woman—Margaret Thatcher who was no less a man than Genghiz—were not necessarily people of vision. It's no disqualification that they were not good either, for Lord Acton held that 'great men are almost always bad'. They were driven by a single idea—power, money, conquest—to become 'accidental' globalists and ride the tides of history. If they helped to shape globalisation, globalisation also shaped them. From his ghetto hideout, the first Rothschild established finance as the pivot of an interconnected world economy. Though not mentioned here, his grandson, Lionel, by then sporting an aristocratic 'de' before his surname, lent Disraeli £4 million to buy the near-bankrupt Khedive of Egypt's shares in the Suez Canal.

Another anecdote Garten leaves out concerns the English socialite Pamela Harriman whose first husband was Winston Churchill's son, Randolph, and who later became American ambassador to France. There seems to have been some confusion between Jean Monnet, 'the diplomat who reinvented Europe', and the French artist, Claude Monet, at her senate confirmation hearings. According to one version, all went smoothly until Senator Jesse Helms, who had never heard of the artist, thought membership of the Monet Society meant she supported Jean Monnet. Another version says Pamela, whom someone called 'the 20th century's greatest courtesan', had never heard of the diplomat, and spoke of the artist when Helms brought up the father of European unity. Either way, the billionaire Pamela had greased enough Democratic palms for her nomination to go through smoothly.

The potted biographies make fascinating reading. But the link is tenuous and, sadly, this book comes at a time when Brexit, the rise of the far right represented by France's Marine Le Pen, Donald Trump's 'America First' pugnacity, the refugee crisis and terrorism have somewhat taken the shine off globalisation. The concept isn't dead. But interpretations are inspired by self-interest. Even Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam's proud inheritors identify the borderless world only with their own yearning for H-1B visas to escape the rigours of the emerging cashless, beefless, goonda- ridden Hindutva.