Picture Perfect

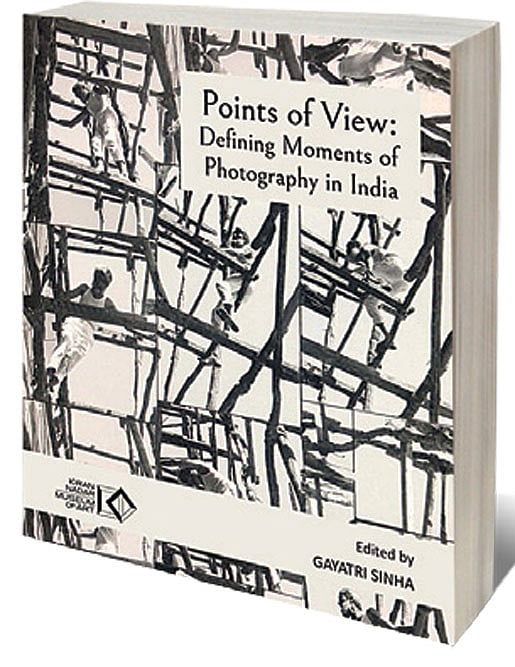

THE IMAGES IN the two volumes edited by Gayatri Sinha for the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) are in a single word—epic. They are sumptuous to behold. They constitute an expertly calibrated tableaux of photographic images that resonate both as objects and as personal testaments to memory, and the way that the past conditions us to view the present. There are salutations to Susan Sontag, the famed New Yorker mediator on the art of photography, as the massive enterprise chugs through different time frames of the history and practice of photography, unspooling reel by reel across the Indian subcontinent. If Points of View seeks to instruct the viewer with a series of carefully chosen essays by eminent scholars on how to approach the collection at KNMA, The Archival Gaze is a freewheeling ride through the material, which spans, as Sinha reminds us, almost 200 years.

One might even describe it in shorthand as Mughal-e-Azam meets Gully Boy. This is not specifically a reference to either of these films but to the notion behind them—the inheritance of a storied past that is continually being referenced in our love for opulent interiors and the celebrity lifestyle; and the underbelly of what takes place behind the scenes. Gautam Bhatia, the architect and brilliantly acerbic observer of our urban environment nailed it long ago when he described it as “Punjabi Baroque”. Needless to note that since then, the hybrid manifestation of our fractured aspirations has managed to mutate into even more exotic singularities. If there is one dominant thread to this extraordinary culling of visual material it is that there is an underlying connection to art, or the artistic impulse that might have led to them.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Given the range and diversity of the discourse one may be forgiven for grazing lightly over such matters as post-colonial tristesse or the fetishising of the subaltern. These issues are dealt with the rigor that they demand with references to all those who have pondered upon them both in words or through their images. This is entirely to the credit of the team tasked by Roobina Karode, who as Director of the KNMA reminds us in the Foreword, “The essays also highlight photography’s synergetic connection with print capitalism and popular cinema, along with the individual practices of self-fashioning and representation.”

There is an excellent chapter on the exacting skills and techniques required to recreate the older prints into their digital form without losing out on their original character. Or as Sabeena Gadihoke in ‘Acts of Translation’ observes, “The focus here is not on recovery of what is perceived to be an absolute truth but on the mediation of history and the passage of time.” To the casual viewer the earlier picturisation of Indian monuments, gorgeously attired princes and their younger children, or paramours, priests and performers feed into our inbred fondness for an imagined past, even if they should include the ceremonial recreations of the Tiger hunt.

Many of these images are familiar enough to us through the works of Raja Deen Dayal (1844- 1905). In an essay entitled, ‘Famous Still: Photography and Celebrity in the Works of Raja Deen Dayal and Dayanita Singh,’ Deepali Dewan by juxtaposing these two very different practitioners belonging to vastly different time frames and societies focuses on what she describes as ‘celebrity culture’. Or as she elaborates, “Scholars of celebrity culture are careful to distinguish different forms of celebrity depending on how the status is acquired—these range from the iconic to the notorious and the infamous. In this essay I look at celebrity as a cultural field, one that was born of a particular historical moment and enabled by the technology of photography.” While starting out by creating formalised portraits of the Indian upper class in the second half of the 20th century, Dayanita Singh navigates her way into different territories that may involve an empty room with a just vacated bed with a wooden mosquito net frame hovering over it, or an empty chair, Van Gogh style. Dewan underlines Singh’s intentions when she explains, “Each image of hers not only documents a person, a thing, or an interior space, it is a document of her own emotion at the moment and what the configuration of the scheme made her feel. Each photograph she produces in this way is a self-portrait.” Needless to add by doing so she becomes her own celebrity.

Turning to the 19th century, Jyotindra Jain’s essay focuses on ‘Pictorialist Photography,’ its advent in the West and inevitable re-invention through Indian eyes. Let us quickly add that even a term such as “Indian eyes” can be problematic as later essayists have pointed out. By looking at the work of two Parsi photographers Shapoor N Bhedwar and Jehangir S Tarapore, Jain focusses on the highly sentimentalised studio photographs that both of them created almost like a tableaux vivant. They were probably influenced by the conventions of Parsi theatre at the time, not to mention the art of the pre- Raphaelite painters in England and the attractions of what came to be called Orientalism in creative minds in Europe. Jain also situates the mythological paintings of Raja Ravi Varma that were eventually to become popular art through their reproductions through a German printing press acquired by the artist within the romantic idioms that appealed to the 19th century bourgeoisie in the west. Whether one classifies these adaptations as cultural appropriation or cross fertilisations will obviously depend on one’s personal reading. That they outlasted their original frames and morphed into advertising, cinema, fashion and politics is, of course, well known.

The social contract, or more correctly, the lack thereof, between those who wield the camera and those in front of it forms part of the ongoing engagement with those involved whether as photographers or agents provocateurs. In the context of the increasing tensions that appear in the daily eruptions of violence that we watch on our screens or share on our electronic devices bring to mind the words of David Selbourne, the British political philosopher who chronicled the 1971 Emergency, “The constant and latent fear of the awesome power of the people, both inchoate and focused, arouses not only the reflexes of paternalism, contempt and hatred, but also violence. The use of such violence is the reflex of power; and redoubled violence, the reflex of power corrupted and additionally embattled.”

Can one pictorialise violence and use it as a reminder of what not to repeat? Some of the most moving testimonials to such acts of communal and individual violence are also included in these pages. Whether it’s of the bullet marks left on the wall of Jallianwala Bagh; the beautiful half buried face of a child its eyes still open in surprise at the midnight horror of the gas leak at Bhopal in 1984; the head of a conservancy worker neck deep in sewage in Sudharak Olwe’s portrait, In Search of Dignity and Justice: The Untold story of Mumbai’s Conservancy Workers—there are enough reminders of injustice.

There will always be those who complain at not having been invited to the ball. In this case it must be the lack of any significant representation from south India. There is not even a nod to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale venues that have created a whole new diaspora of photographic images. There is however an image of Quick Gun Murugan. In a sense this brings a much-needed lightness—photography can also be fun.