Peace and the Pachyderm

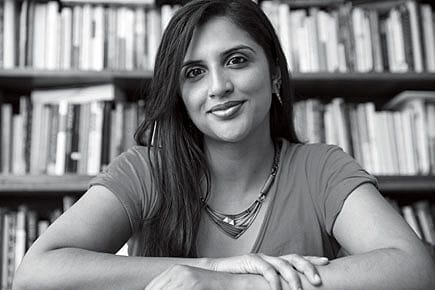

Trade in ivory has been banned for decades in India. Tania James takes man's increasing inability to live peaceably alongside the elephant as the subject of her second novel. Her debut, nearly six years ago, was the well- received Atlas of Unknowns, followed in 2012 by Aerogrammes, a collection of bijou stories, their sometimes overly winsome prose undercut by surprisingly sharp jokes. One of the stories, 'What To Do With Henry', describes the adoption of both a small girl and a chimpanzee from Sierra Leone. When a boy at school asks the girl if it's true that her brother is a chimp, she reflects: 'The correct answer to his question would have been: Henry's not my brother, he's my pet.' Can the distance between chimpanzee and human be bridged?

Henry, attracted to blondes, with memories of his life with his mother and sister that he cannot erase, finds it difficult to be fully chimpanzee, just as he cannot be fully human. There is an echo of this struggle in The Tusk That Did the Damage, in the relationship rescued calves—elephants orphaned by poachers—share with their 'pappans', the men who feed, bathe and care for the elephants. Mired in grief for their mothers, the calves were 'coaxed and bullied' by pappans 'from the brink of despair': 'His was an arsenal of soft words and soft blows, plus the odd nugget of sugar'. James writes feelingly of the relationships between the elephants and their human keepers, as she did between Henry the chimp and his human family. Trust and loyalty is hard won but the essential distance between species is unbridgeable.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Something of this distance is evident in the way James adopts the first person for her human narrators, a young American documentary filmmaker and a poacher's reflective, introspective brother, but maintains the third person in the chapters told from the point of view of an elephant (these three points of view form the three parts of the novel). This elephant, the Gravedigger, a specimen of pachydermal perfection, is so named because of his habit of tastefully covering the bodies of his victims, the people he lays waste to on homicidal rampages. Empathy, James says by her alternating use of perspective, is possible, real feeling, but humans cannot fully inhabit the personas of elephants.

She comes close, though. Life for the Gravedigger has been, in the Hobbesian formulation, nasty and brutish, if not particularly short. Traumatised by his mother's death, he is briefly revived by the care of his pappan and then sold into service, appearing in religious ceremonies and weddings, subject to human crowds, noises and smells: 'The drums were deafening, but nothing compared with the barrel rockets so thundersome they skewered the heart… passed through the body like an explosion, like the explosion that stopped his mother's breath.' The Gravedigger is later attacked by a frenzied, drunken pappan armed with a pitchfork. It's the sort of back story that might turn anyone into a murderous sociopath.

What excuse do poachers have? Greed perhaps. Though poachers are lowest on the totem pole, paid derisory sums by the powerful criminals in the city who profit from the trade in ivory. Perhaps also anger at the wild elephants who destroy farmers' crops and kill their relatives; perhaps theirs is a life almost as nasty and brutish as that of any elephant. James' narrator in these particular chapters, Manu, the poacher's brother, is compelling: a young man muddled by desire, ambition, loyalty, love. James is as skilled at evoking sibling relationships, their mix of competition and devotion, as she is at describing the bonds between elephants, between mothers and their children, between elephants and their pappans. If in these sections the plot is contrived it is because by the end, The Tusk That Did the Damage transforms into myth, into fable. By the end, the Gravedigger, with his capacity to dole out life and death, is more god than elephant, more sublime than beast of flesh and blood, and the poacher and his brother are in awe. The novel's tripartite structure, however, is weakened by the sections narrated by Emma, the 23-year-old American documentary filmmaker who arrives in South India with her classmate and collaborator to make a film about a charismatic vet with—naturally— a movie star's jawline. The stakes, for elephant and man, are high in the rest of the novel, but in these sections nothing is at stake. The coming of age of a college-educated American naif, with her callow, received ideas about art, about morality, about corruption, and her relationships with two men, is not only out of place in this novel but uninteresting.

There is beauty and horror in man's relationship with animals, with nature. It's not an original observation, but, as James shows in this affecting novel, it's one we still need to have made for us.