Parini Shroff: The Queen’s Gambit

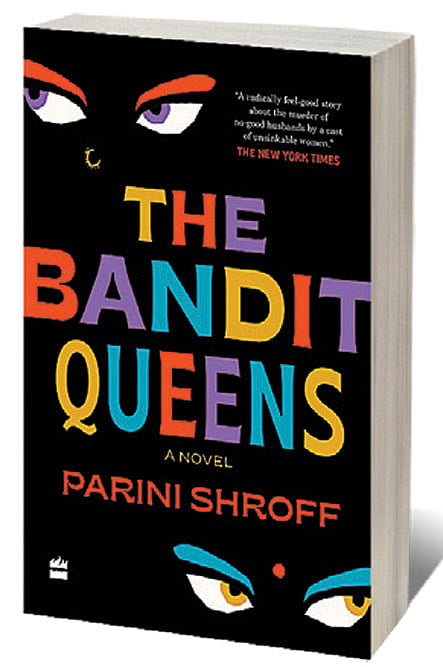

PARINI SHROFF’S ASSURED and entertaining debut novel, The Bandit Queens (HarperCollins; 352 pages; ₹499) can, perhaps, best be described as ‘rollicking’. Geeta, her protagonist, is the kind of hero that one feels India and Indian fiction both sorely need. Surly when we first meet her, Geeta “no longer had friends, but she did have her freedom”. Ostracised by her village after her alcoholic husband suddenly abandons her, Geeta is thought of as a murderer and churel. In the five years since Ramesh left, she has made ends meet by sustaining a small mangalsutra business that she finances with a microloan.

Speaking over a Zoom call from her home in Mountain View, California, Shroff says she always meant Geeta’s craft and profession to be a “little ironic”. Fiercely independent in her life and views, it seems strange that Geeta would sell necklaces “no prettier than the rope tying a goat to a tree, depriving it of freedom”. But Shroff, for her part, adds, “I did not want to make any sweeping claims about the entire institution of marriage. A mangalsutra means different things to different women.”

The Bandit Queens is not the kind of novel where the protagonist alone is made to lift the weight of her author’s intent. Shroff has populated her book with a cast of women who are as spunky and sassy as they are spirited and indomitable. There is Farah, the talented tailor, who wants to kill her abusive husband to save herself and her children. Saloni, Geeta’s friend-turned-foe, has the kind of heart that guides the flow of the novel like a lighthouse, while Khushi, a Dalit corpse burner, is funny and practical.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

“I think each of these characters uses their circumstance, and the assumptions made about the said circumstances, to their advantage,” says Shroff. “Khushi uses her work as a corpse burner for economic benefit. She charges some people more than she would others. Saloni uses her beauty, and the assumptions people make about it, to her advantage by trying to manipulate people, especially men. Farah is not as dim-witted as she seems. These women survive oppression by using it for their benefit.”

As Geeta’s path begins to intersect with those of these women, she is forced to get out of her crab-like shell. Farah makes her an accomplice in her husband’s murder. Saloni buries the hatchet, and Khushi, a minor character at first, once comes to feel like Geeta’s only hope. “Geeta’s character seemed more solid to me when I put her in a room with these other women. When the other women are being funny and bantering or complaining, Geeta becomes a foil. I wanted to show a whole range of women.”

Even though Shroff gives all her women a sense of humour, it sometimes becomes hard to tell where comedy and tragedy might lurk in her book. When more women in Geeta’s village grow thirsty for the blood of their good-for-nothing husbands, Shroff lightens the tensest of scenes with jokes and gags that all have the potential to make you laugh out loud. The book’s hilarity, however, never undermines its urgency. “My characters make questionable decisions throughout the novel,” says Shroff. “These women have gone through the pros and cons, and they have very clinically decided that murder is the best and only route. I wanted to examine what drove them there, not so much the decision they make.”

AT ALL TIMES, the narrative of The Bandit Queens resists a stereotype it sums up well in a single dialogue: “Women were built to endure the rules men make.” Geeta resents being put in positions where her only choices are “violence” and “violation”. Shroff writes, “She didn’t want to be built to endure, a long-suffering saint tossed by the whims of men. She wanted, for once, not to be handed the short end of the stick by a system that expected gratitude in return.” Through Geeta and other characters such as Farah and Khushi, Shroff seems to repeatedly ask, “Why can’t we try for new rules?”

Of the view that “equality” should extend to our workplace and relationships, the “new rules,” says Shroff, “should really be based upon each person and what they want. Yes, what works for one won’t necessarily work for another, but you should have the opportunity to gain what you want, as opposed to someone else telling you what equality is.” Though the novel often stops to underscore the value of personal want, Geeta finally finds relief in friends and community. Shroff adds, “When Geeta forges these grudging friendships, she sees her life can be more fulfilling by making herself vulnerable to rejection. If you open yourself up, there is a possibility of strength in numbers, as these women prove.”

Geeta has pinned above her workstation a picture of Phoolan Devi. She finds in the Bandit Queen a courage and resolve she wants to emulate. Farah, at one point, tells Geeta, “I think [Phoolan] was capable of anything because everything had already happened to her. She’d been beaten up and raped and betrayed so many times by so many. She was fearless because she’d already suffered what the rest of us live in fear of.” Phoolan Devi comes to Geeta often when she hits rock bottom, but even when she is enjoying the rare pleasure of intimacy, her mind wanders to India’s most popular woman dacoit. She thinks, “In a world where her vagina was a liability, was there even room for petty things like love?”

In her afterword, Shroff writes that sometimes while writing, she would stop to ask herself, “Is this honouring Phoolan or exploiting her?” Even weeks after her novel first released in the US, Shroff says, “She is not with us, so I will never really get an answer. But I hope readers will see what the intent was. I didn’t want to co-opt her story. I wanted to use it as a source of inspiration for all these other women.”

Seeing how Phoolan Devi had become a thread that tied the novel, Shroff always knew that she risked filling too many blanks for well-informed Indian readers. “It seemed important enough to take the risk and maybe seem repetitive to some readers but to educate others. There is a line you must walk. It’s a tightrope you navigate, so sometimes you are going to fall.”

Impatient audiences might perhaps want to fault Shroff for over-explanation in some instances—she does once feel compelled to describe jalebis as “bright orange, shiny wheels”—but even they would have to concede that the author rarely ever spoils a joke by labouring to simplify it. When Geeta tells Saloni, “I swear to Ram, this bogus story is longer than Draupadi’s sari,” Shroff does not feel the need to give her readers the context of the Mahabharata. On hearing of yet another murder being hatched, Farah says, “We can’t just knock off everyone we don’t like. This isn’t Indian Idol.” Shroff tells us, “I wanted the humour to be for everybody, but if you happen to be of Indian descent, then you would enjoy the humour on a different level—the Indian Idol and Koffee with Karan jokes, for instance.”

When Shroff finds life absurd, “especially when it’s dark”, she actively seeks “humour, irreverence and irony”. Her writing, however, took on these qualities only after she started writing The Bandit Queens in 2020. “The fact of the matter was the humour kept creeping in and I kept shoving it away, because I thought it would undercut my point. And it got to a level where I would edit myself before I would put myself to write.” Shroff soon decided to stop policing herself. “I stopped denying the humour that was demanding to come in. Once I leaned into the fact that this was going to be a dark comedy, it became more about what served the humour the best.” Shroff adds that with The Bandit Queens, she wants to “educate, but also entertain. Once you do that, you can be of some help in the fight against ignorance.”

LONGLISTED FOR THE 2023 Women’s Prize for Fiction, The Bandit Queens espouses an unapologetic and exuberant feminism. Shroff acquaints us with “the vast emotional gamut of women”, their equally capacious “cruelty and kindness”, but gender in her novel often intersects with caste and religious discrimination, too: “Their village spotted caste on sight like it was gender and behaved accordingly.” Shroff says, “Dowries are discussed very briefly, as are child marriages, but these things are not isolated. They intersect. They are mounted on each other. There are points when the misogyny, the patriarchy and domestic abuse all meet the double oppression of Dalit women versus women of caste.”

The Gujarati village that Shroff imagines is a “composite of various villages”. Alongside inventing the rules of her novel, the author says she also had to invent the rules of the village. “I needed the village to be autonomous and self-ruling. I needed it to make its own rules. That is what makes these women feel like they have a sense of agency. They can commit crimes and get away with it. And, so, that kind of village logic, if you will, is what made various plot points possible for me from a logistics viewpoint.”

Having moved to California when she was just “five or six”, Shroff, 37, returned to Ahmedabad in the summer of 2013 to spend time with her father and brother. “At that point, my father was involved in financing a microloan group in Samadra, a village outside of Ahmedabad. We took a day trip, and we got to sit in on a microloan meeting, where the women congregated on a porch to repay that week’s loan payments.” Shroff saw how money led to empowerment. “It’s difficult to overestimate the pride one can have in providing for your family, yourself, your children. It lends itself to confidence as well as upward economic stability.” The author’s thoughts, however, exceeded commerce. “Since I am a novelist, my first instinct was to ask ‘what if?’ What if something spicier or darker would happen?”

Ten years ago, Shroff had fictionalised her experience of Samadra as a short story, but when she returned to it during the pandemic, she saw a larger world unfold. “It became a novel.” Relying on her memories of various villages in Gujarat, Shroff used YouTube to refresh her recollections. “I started to watch YouTube videos that people uploaded randomly from their mobile phones, while wandering through their own village, living life. I would suddenly remember the smell of firecrackers, or the smell of trash burning. It would trigger these other memories, and I could then build the world.”

The world that Shroff builds for her readers feels wholly authentic. Even though her characters sometimes spout Americanisms in rural India, you trust her implicitly. Rather than be a stickler for accuracy, Shroff is more interested in conveying emotion. Even at its most outrageous, Bandit Queens makes you root for women who only get a taste of justice when they take it in their own hands. As a practicing attorney, Shroff thinks of justice as remedy, one that “will give a wronged person the ability to move on”. In a novel that often makes you think of comeuppance, justice feels more fluid than fixed: “Justice must help people go on to who they want to be, as opposed to a kind of justice that keeps them locked in amber, where they feel frozen in a certain moment. That cannot be justice.”