Our Land and Our Self

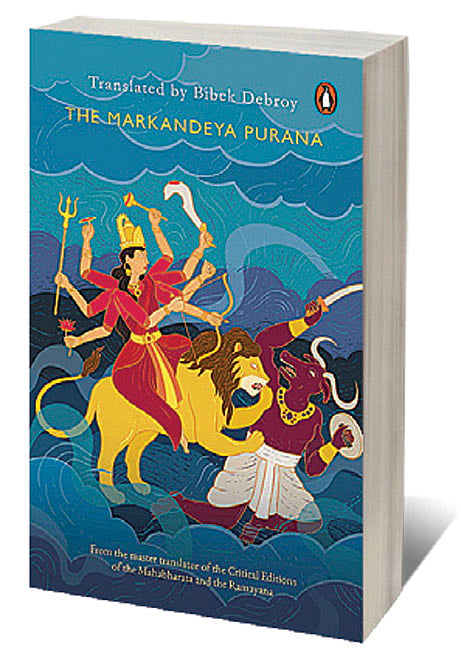

AS WITH ALL other ancient Indian texts I’ve read, the Markandeya Purana pushes the boundaries of dharma, throws characters into fires, creates situations that stand on razor’s edge and sharpen dharma. This Purana then sits back and watches how individuals engage with dharma, societies evolve through it, nations live it. Coming straight after reading the Mahabharata, we meet old friends (Mandapala and his sons), make new ones (Harishchandra), explore the nuances of a goddess created by energies (Devi Mahatmya), reinterpret eternal ideas (the Vishvamitra-Vasishtha fight being driven by tamas) and explore the fluidity of caste across lifetimes (Sumati), each of which delivers eternal truths.

We question the ‘wisdom’ of rishis whose tests border on cruelty and get respite from the gifts received when characters pass those tests. We cry for characters, as we see them, imprisoned by morality, hurtling towards self-destruction. We get cathartic relief when we see victory of the righteous, of dharma. And at some point, we become the Purana—we are Markandeya, we are his creator Veda Vyasa, we are their translator Bibek Debroy.

Such is the intensity of Markandeya Purana, one of the 18 major Puranas that, along with the Vedas, the Upanishads, the epics and dharmashastras, forms the edifice of Indian civilisation and its infinite extensions. The Puranas are composed by humans (smriti), unlike the Vedas that are received directly from the divine (shruti). Above all, as we transpose characters, situations and moralities of our 5,000-year-old civilisation on present-day India, we receive all the tools needed to enact our own life-scripts.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Deprived of this knowledge in our educational system, it is a miracle how these texts have survived. Clearly, the efforts of rishis of the past and translators of the present have helped. And Debroy’s Markandeya Purana gives us one more pillar to build on. To give a small but intense window, just one chapter (39th) captures the essence of the word ‘Oum’, an idea-word-sound that is the sublime symbol and motif of Indian civilisation. As we negotiate the 21st century, we see the path, we know the right thing. Our digital exhaust is tracked like never before, our actions questioned and put under the lens like our ancestors were. Out of all this will emerge the future Purana, rooted in the wisdom of the past.

The Markandeya Purana is not an easy read—we can’t race through the 560 pages. And it’s not just because of the philosophical depths that Debroy takes us through in this modern translation that make us pause for breath and understand contexts. The language and the ideas it contains within it are equally intimidating. It’s like a non-swimmer being thrown in the deep end. And yet, with calm and grace, with a mind open to scepticism as well as faith, we swim these deep waters of knowledge and reach the shores of wisdom.

As one of the world’s living master translators of Sanskrit texts, Debroy is a lifeline as well as a lighthouse. After having translated the Bhagavad Gita (2005), the Mahabharata (2015), Harivamsha (2016), the Valmiki Ramayana (2018) and the Bhagavata Purana (2019), we can see a greater force in his translation, a sharper conviction and authority in his footnotes, a deeper wisdom honed by practiced ease. In fact, his footnotes add as much to the text as they explain, a skill he has adapted from his expertise in the domain of economics. Reading them forces us to think beyond the book. They are a source of information on a vast range of issues, through the medium of storytelling.

‘In the absence of svadhyaya, vashatkara, svadha and svaha, how can the destruction of the entire universe be prevented,’ the gods ask and Debroy translates. But he doesn’t let the translation stand empty, he explains it in his footnote: ‘Svadhyaya is self-study, interpreted here as recitation of the Vedas. Vashatkara is the exclamation ‘vashat’ made at the time of offering an oblation. Svadha is said at the time of offering oblations to the ancestors and svaha is said at the time of offering oblations to the gods.’ Such explanations, spread across the pages, enrich the primary text for those not versed in the language of rituals.

As a student of the dhrupad form of Indian classical music, I found the footnote on notes and beats to be thought-provoking. ‘The seven svaras [notes] are shadaja, rishabha, gandhara, madhyama, panchama, dhaivata and nishada; gitika is also a metre, not just a song, since there is no list of seven songs, this might mean the seven metres; murchhana is moving up or down the scale, with seven svaras to start, there are thus seven murchhanas; tala is the beat in time in music and the number is not invariably listed as forty-nine; the three gramas [octaves] are udara, mudara and tara.’ These footnotes strengthen the dialogue and the story that contain the main ideas, they anchor us to the present while exploring the past, they root us to our civilisational legacy while living in the modern age, exploring contemporary ideas.

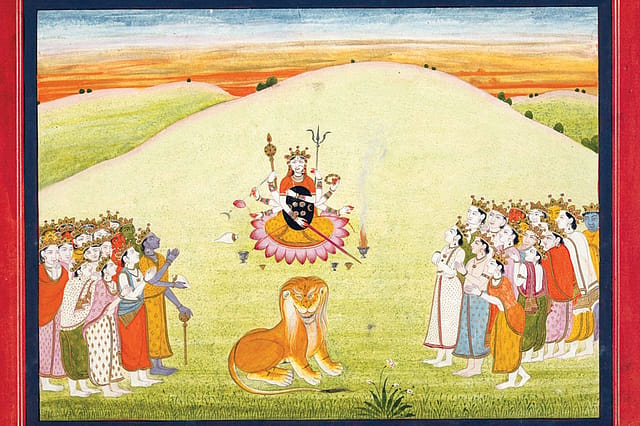

In the world of storytelling, much of our ancient legacy is carted on the conflicting currencies of violence and wisdom, descriptive and poetic. The 13 chapters on Devi Mahatmya (78th to 90th), for instance, are like watching a cutting-edge Netflix series. Across 590 shlokas, the Devi expresses her strength and gives it to us. She destroys Mahishasura and warns us. She is wise and shares her wisdom with us. Feminists will love her, the faithful will worship her, scholars will explore her exploits, and filmmakers will get a new creative energy from what is essentially a collection of forces. These inspiring chapters are the heart of the book. I read them twice over.

A Purana, as Debroy explains in his insightful introduction, has to possess and discuss five attributes—sarga (original or primary creation and destruction), pratisarga (smaller and secondary cycles of creation and destruction), vamsha (genealogies of gods, rishis and kings), manvantara (a period during which a Manu presides and rules over creation) and vamshanucharita (lineages and conduct of kings). Beyond these five traits, a Purana is also a description of geographies, geology and astronomy. In other words, a Purana is an encyclopaedia of physical traits, explorations of social organisations such as varnas and ashramas and inner layers of metaphysics and spirituality. The Markandeya Purana delivers all this and more, inviting us to explore both, our land and our self.

After reading the Mahabharata, I had asked Debroy, how much of the translation was Veda Vyasa’s and how much of Debroy was lurking there? He said that the entire text was Veda Vyasa’s, the footnotes his. After reading Markandeya Purana, I asked him, how do you create paragraphs? He said that whenever he feels that a particular part of a discussion is over, he makes a para. To see Debroy’s signature on these texts, therefore, there are three tools: the contemporary language, the footnotes and the paragraphs. The language differentiates his work from that of, say, Manmatha Nath Dutt’s 1896 translation or Frederick Eden Pargiter’s 1904 translation. It is easier for a modern reader, in tune with the evolution of the English language. The detailed table of contents in Pargiter’s translation, however, was very useful and I hope Debroy will reintroduce them as he translates the Brahma Purana now.

Debroy offers scholars the opportunity to work across these repositories of knowledge. The kingly duties (chapters 20-27), for instance, reflect in spirit the ‘Shanti Parva’ of the Mahabharata. Dharma and its complexities bind characters across Indian texts. The listing and description of seven types of hell— Rourava, Maha-Rourava, Tamas, Nikrintana, Apratishtha, Asipatravana, Taptakumbha—each more terrifying than the other, leave us wonderstruck at the imagination, the poetry and the knowledge contained in this Purana.

Reading English translations of Sanskrit texts requires four skills. One, the ability to understand ancient Vedic contexts and spiritual frameworks that may or may not be visible to the modern mind limited by the scientific method. Two, the ability to visualise ideas beyond the boundaries of language, all the while knowing there could be a five-millennia-old civilisational reality behind the words, an evolving reality that continues to influence an evolving India. Three, the love for Indian knowledge, stories, poetry, offered to the lay person in an accessible form, delivering the knowledge of science and statecraft, spirituality and order, the quad of dharma, artha, kama and moksha, through the medium of storytelling. And four, approaching the work and the translation with the hermeneutics of respect. The degrees of difficulty in reading these texts are not only linguistic and idiomatic but contextual and situational. As a reader I found it was my third skill—love—that allowed me to overcome the first two hurdles and power the last enabler.

We are in deep gratitude to Debroy for undertaking this self-actualising and selfless task and patiently wait for him to complete all the 18 Maha-Puranas. A must for scholars and seekers of India’s civilisational legacy, the Markandeya Purana offers us a new window with which to look at the essence of our nation and re-examine who we are. And until we can rediscover ourselves in the original Sanskrit, Debroy’s translations take us to that light.