No Man’s Land

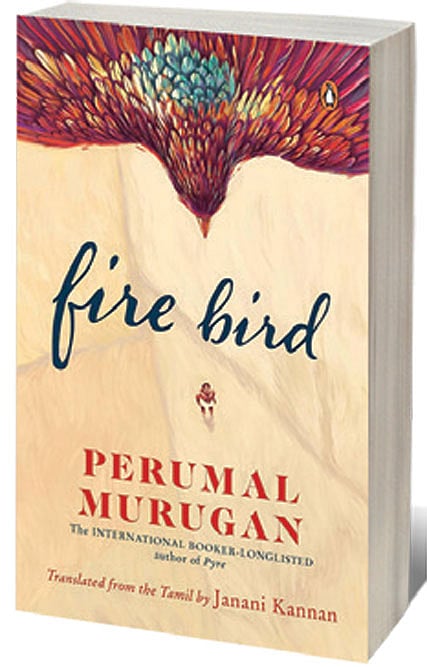

THE SENTENCE “As adults, however, it would seem that affection disappears and rightful heirship trumps everything else,” is voiced by Muthu, in Perumal Murugan’s latest and twelfth novel Fire Bird. This fact drives the book’s plot, and is also one of several uncomfortable truths that confronts the reader.

The novel, originally published as Aalandapatchi in 2012, has been translated from Tamil to English by Janani Kannan, and won the prestigious sixth JCB Prize for Literature on November 18. It is also the fifth translated novel to win the prize. Fire Bird is set in Tamil Nadu 60 years ago, and is centred around Muthu, born into a poor agrarian family. The novel illustrates the dark side of inheritance when Muthu’s parents divide their family land between their four sons, with the eldest seizing the lion’s share of soil and water, and leaving the youngest, Muthu, with a pittance. Disillusioned, Muthu soon ventures forth to find his own plot of land far away from his joint family, where he plans to settle with his wife and children. His travels with Kuppan, his in-laws’ lower-caste servant, in search of his ideal new site, take up much of the book.

Although Muthu and Kuppan find the site within the first few pages, it is evident their journey is only beginning. In fact, the book shifts back and forth in time, slowly unfolding the event which so abruptly transformed Muthu from being the cossetted youngest son and brother, to being the one with the least. The property division immediately creates discord, turning brother against brother and sending sisters-in-law and the mother-in-law into further disharmony. Murugan reveals how the hypocrisies in the patriarchal setup that prove the potential for the family split were always present.

Fire Bird also demonstrates how the continuing power of feudal relationships lies in the family, and how land can tear apart the closest bonds. Muthu has great difficulty moving beyond this. “It still hadn’t dawned on him that the times when he rode on his eldest brother’s shoulder… now belonged to the past.” His subsequent quest for a new permanence and stability can only be achieved by finding his own land. Land, all important for farmers, is a recurring theme in Murugan’s novels. It can be traced to his first novel, Rising Heat (1991). The themes of displacement and forced migration are also explored there, as they are in Fire Bird, and are portrayed through the struggles of ordinary families. At one point, Muthu despairingly wonders, “Where were we born and where do we die?”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The issue of caste, also found in his other books, is portrayed as bleakly here. The shackles of the caste system are clear as Kuppan is overly grateful and servile in return for Muthu’s kindness and consideration. Muthu also vividly remembers a pandal that served free food, but with inferior rice served at the back for the lower caste. Other themes such as the double standards of sexual violence are also explored when Muthu’s wife, Peruma, is assaulted by her older brother-in-law and her mother-in-law condones it. Peruma, the titular ‘Aalandapatchi’ or the Fire Bird, and the most sharply drawn character, repels the attack. Her mother-in-law gives her the name because of her sharp tongue, but the Fire Bird can also be a symbol of hope. Peruma constantly taunts and reproaches Muthu over their new circumstances, and proactively contributes to his finances. It is she who pushes Muthu to search for land for their own nuclear family away from her in-laws.

Fire Bird, like much of Murugan’s work, although powerful and fluidly written, is also painful and often difficult to read. The pace and its stark, grim narrative leave the reader constantly on edge and anticipating some disaster on every page. However, it is also characteristic of Murugan that there are moments of hope, along with acts of genuine selflessness. It also follows Murugan’s tradition of highlighting realities often unknown or unacknowledged, by modern urban readers, which they prefer to ignore.