Moore’s Second Coming

FUTURE HISTORIANS will perhaps call our times the Age of Superheroes. And Alan Moore is one of the makers of that universe. In the words of Michael Moorcock, he is “a modern urban shaman” of the 21st century, a “visionary who acts on behalf of the people, putting all its emotions, fears, hopes, and aspirations into words and pictures.” His CV, extraordinary as it is—Watchmen, V for Vendetta, From Hell, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, John Constantine (the DC Comics character)—doesn’t capture the influence he wields. The pipeline of comic books to film, the turn towards dark and gritty reinventions of characters, the idea that conspiracies underpin our reality, Moore is both the voice as well as the shaper of the zeitgeist. When I ask him a question about V, he says it is part of the “95 per cent of my work that I have disowned”.

While he still loves comics, “It is a wonderful medium to work in and its surface has barely been scratched,” he says that “the comics medium is dominated by the comics industry, and the comics industry is corrupt, and I think largely worthless.”

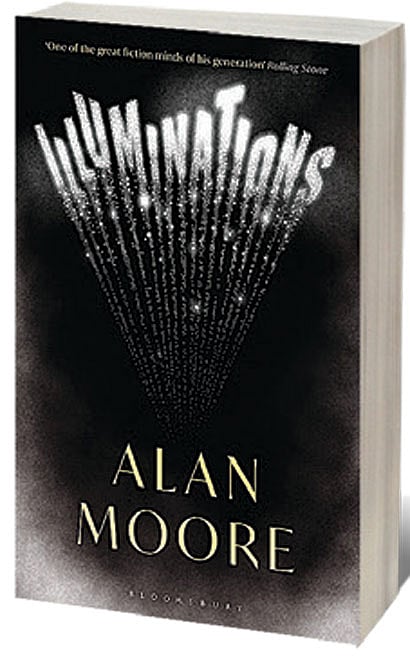

Because of this, Moore famously retired from comics in 2018. With his debut collection of short stories, Illuminations (Bloomsbury; 464 pages; `699), he has opened a second innings in an already stellar career. Half of the nine stories were written in the white heat of the first lockdown, between February and August 2021.

Moore has worked with incredible artists, with whom he has wrought an alchemy of word and image. But now, as a prose writer, it is all words, all him. There is a sprinkling of frost in his voice when I suggest that not having an artist “picking up the slack,” could perhaps put pressure on his writing. “I wouldn’t say that I’m letting the artists pick up the slack because my comic scripts are very, very detailed. And I am trying to imagine the scene that I want the artists to draw in incredible detail, in my panel descriptions. Whereas if I’m working upon, something like Illuminations or Jerusalem, (his 2016 novel), then I’m aware that I’ve got to do the same descriptive work, but for the reader rather than an artist. And if I’m doing it for the reader, I have to do it in much finer language because if I’m describing something for an artist, then it’s in very blunt, practical terms. Whereas if you’re describing something for a reader, you want the language to soothe them and to invite them in and to seduce them, if you like, to hypnotise them and to draw them into the story. So, I’m doing the same amount of descriptive writing. It’s just with a novel or with short stories it takes me a bit longer because I want to put a polish on that raw thing, but it’s pretty much the same process.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Moore’s personal favourite of the nine stories, in Illuminations is ‘The Improbably Complex High Energy State,’ which describes the beginning of the universe, “it was the best of times; it was the first of times,” with imagery that wouldn’t be out of place in the building of Pandemonium in Milton’s Paradise Lost. “That was born of me thinking about entropy,” he says about the story. Did he study science? He chuckles. “Being ejected from school at the age of 17, I had to take over my own education myself.”

BORN IN NORTHAMPTON, in 1953, Moore was expelled from school for dealing LSD. After expulsion, he was involved in an arts lab, a local creative community that saw him develop his craft, initially in art. After drifting through a series of menial jobs including head toilet cleaner at a hotel and chief skin shearer at a tannery, he found stable employment as a clerk in a gas pipe company. By now married, and with his wife expecting a baby, he still yearned to break into the creative field. With his wife’s blessings, he quit his job, and gave it a go. After an attempt as a cartoonist, where he created Maxfield the Magic Cat, an “antidote to Garfield,” he decided to switch to script writing and got on board with 2000 AD, a then fledgling comics magazine where his stories soon became fan favourites. A star was born.

“I have no formal training in anything, not in writing, not in science, not in art, not in any of the things that I am often called upon to talk about,” he says, “the thing that I like to do is to have fun with scientific ideas.”

‘The Improbably Complex High Energy State’ is typical of Moore’s combination of ambitious storytelling and deep research. It takes place within the first femtosecond of the universe being created. He writes, “If a femtosecond lasted for a second then a second would last thirty million years.” In this vanishing moment, “I will be able to show a rehearsal for the entirety of sentient life, we can have ridiculous love stories and stories of betrayal and stories of empire and warfare.” Moore dives into the seething plasma, where “from the fizzing symmetry, as multiplying stadia unpacked themselves from empty vacuum everywhere about, a rumour of sub microscopic particles converged with highly ordered randomness upon a striking new configuration…as choreographed accident, untrammelled by unlikelihood, the scrum of proto-atoms and incipient molecules collided into a foreshadowing of organism.”

Moore, who is a practising magician, has hidden a rabbit, in the form of, ‘What We Can Know about Thunderman,’ a 240-plus-page novel-length work, within Illuminations. It is a secret history of a secret history. Moore shows off his formidable arsenal, cutting between 1959 and 2015, ostensibly following the career of Worsley Porlock from comics superfan to editor. Porlock is obsessed with Thunderman, essentially a stand-in for Superman. The story is filled with such disguised characters both real, and make-believe. It advances through formal narration as well as forum posts, movie reviews, listicles, comic book scripts and police interrogations.

MOORE IS FAMOUS for not using a smartphone or computer. His only concession to modernity is a fax machine. To say he is publicity shy is an under-statement. And getting an interview with him is rare. For this interview, I had to call him on a landline at his home in Northampton, UK. As a comics reader and creator, Moore is as close as I’ll get to divinity. When I call (at the wrong time, because of a miscommunication), he says simply, “If you just let me get my cup of tea and sort myself out.” While he has disowned his famous creations such as Watchmen and V for Vendetta, to comic book fans he will always be a legend.

On the phone he tells me that he has reams and reams of printouts of Reddit forums to understand the mind of the Millennial. I tell him that there are now Reddit pages dedicated to knowing who is who in ‘What We Can Know about Thunderman’. He says it’s a waste of time. “It is not a roman-a-clef,” he explains. “It is not a novel with a key where this character is this character and this character is another character. Most of the characters are kind of composites, they are meldings of different people. I’ve taken bits from various anecdotes, various people, people that I did know, people that I didn’t. And I’ve tried to come up with representative composites of the kind of people that you are likely to find in the comics industry, but there are no specific people in there. Then he pauses. “I suppose that Stan Lee is probably identifiable.”

Suffice it to say, in ‘What We Can Know about Thunderman,’ a washed-out hack is approached by the CIA as public revulsion is developing against all things nuclear, with stories of mutations and freaks. As the character’s CIA handler says in a long disquisition, “What if there were stories where the people get irradiated, but instead of ending up with leukaemia or something, they turn into super-guys?” He adds, “Atomic energy has made America into a super-power, so maybe it could do the same for individual citizens.” Individuals like a student who is bitten by a radioactive spider for instance, and then turns into a superhero.

Moore doesn’t have time for the proliferation of superheroes. “Over here, people talk about how they’re comics fans. When you talk to them, you’ll find that no, they’ve never actually read a comic. What they mean is they are superhero movie fans. And I will always love the comics medium. I deplore the comics industry and part of that is because I think that certainly in the West, superheroes have become toxic.”

He adds, “The whole root of the concept of superheroes and what it has become, I find it very unpleasant. These are characters that were created to entertain the 12-year-old boys of 50, 60, 70, 80 years ago. And the fact that they’re now an accepted part of adult culture, to me, it seems very much like, that it’s emotionally arrested, the development of a lot of its audience, and I do think that the whole superhero ethos has primed a lot of the audience for extreme right-wing politics. That we’ve seen over the last five years.”

Moore is more supportive of a Reddit thread that has internet sleuths accurately identifying the gruesome 12th-century anecdote, which forms the basis of the last story in Illuminations, ‘And, at the Last, Just to Be Done with Silence’. “I’m glad that there’s discussion about actual history,” he concedes.

Throughout the book, certain themes predominate: nostalgia, memory, looking back at what was, and reflecting on why things didn’t work out. Moore isn’t looking back though. Illuminations is only the opening shot. 2024 will see the release of the first book of a vast pentalogy set in London. He has to turn in the manuscript in six months, but he isn’t too concerned. “Compared to the comic industry deadlines, this is fairly easy going.”