Moni Mohsin: Flights of the Butterfly

IF YOU ARE a South Asian writer in the UK, you have a choice: you can be funny or you can be brown.

A few years ago an editor told Pakistan-born, London-based Moni Mohsin she liked her writing. But humour from her “part of the world” didn’t sell here. British readers, the editor explained, hankered for the “darker stuff”, the “serious, hefty issues”.

“Do you mean poverty, trauma, caste?” Mohsin recalled asking. She did. She was told: “We don’t want funny novels from the subcontinent because nobody’s interested in humour from the subcontinent.”

Mohsin, a journalist and columnist, didn’t say it out loud, but she mulled these high fences for South Asian novelists. “White people can write science fiction, they can write humour,” she says on the phone from London. “We read PG Wodehouse; we don’t know anything about that world. How many of us know about upper-class rural Britain, the aristocracy, and its foibles? But we can still relate to the human stories behind it. We can still laugh and give you that pass. You won’t allow us. All the books from the subcontinent you see which get great praise in the west are usually books about poverty, caste, religion.”

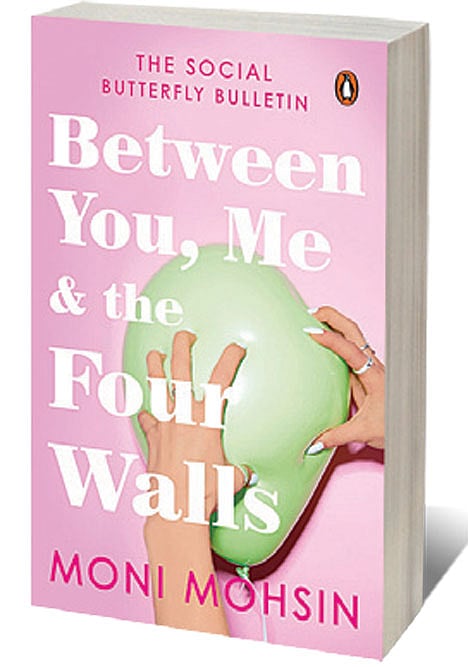

Mohsin’s latest book, Between You, Me & The Four Walls: The Social Butterfly Bulletin (Penguin; 232 pages; ₹ 299) however, contains none of these doom-and-gloom themes beloved of the west. Geared to desi readers, it’s a comical, anti-exotic novel, where social commentary comes delivered to us by a socialite. The central character is simply known as Butterfly, a party-going, status-chasing, convent-educated woman who cogitates on national politics (terror attacks, wars, mob lynchings) and domestic politics (in-laws, house help). Butterfly chunters in the same breath about Imran Khan as she does about her highbrow husband Janoo. The chapters are short diary-like-entries featuring Butterfly’s latest musings—dated between January 2014 and December 2021. “I put her through life as it unfolds,” says Mohsin. “So, I look at the world of Pakistani politics and society through her eyes.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The character started out in a newspaper column in the 1990s, in Lahore’s Friday Times on the “rich and inane” as Mohsin recounts in The Diary of a Social Butterfly (2008), the first Butterfly book. The latest is a continuation of her mispronunciations and misadventures.

Butterfly comes at current affairs with her own peculiar slant. When Modi announces demonetisation it sends Butterfly scurrying to safeguard her cash for designer clothes. And when Covid hits, Butterfly’s social life receives a body blow. Bad things like disease and war can mean worse things like missed lunches and forfeited pedicures. “People say it is such a privileged elitist thing to write, of course it is privileged, of course it is elitist,” says Mohsin. “It’s satire, it is meant to satirise society and ridicule these kinds of concerns. When people say it is elitist, I say, ‘Well, you are missing the point.’”

Mohsin’s sharp critiques, tucked into Butterfly’s glib chatter, land with stealth. In a passage from 2018, for instance, she waxes nostalgic about the reign of General Pervez Musharraf. “Such nice nice balls we were having during his time and no one constantly worrying kay are we going to get marshall law because we already had marshall law.”

Much of the fun emerges from her unique argot of Hindi-Urdu-English; lapsing into taubas, hai nas, and vagheras alongside mangled Britishisms. One might get “knocked up by a truck”, “slip into a comma” and have a “photogenic memory”. Malala is a “stool of the west” and international art shows are the “Venice Banal and Sydney Banal”.

With a gossipy socialite at its centre, and a woman author behind it, the Butterfly books have often been marked as “chicklit”. “I have no control over how readers read,” says Mohsin, on that categorisation. “That’s their freedom and once the book is out of my hands and it’s published, it becomes theirs. I think I’m writing social commentary. But if they engage with it as chicklit, fine, that’s their prerogative.”

Though Butterfly betrays traces of sympathy, or genuine feeling from time to time, the character’s shallowness defines her. Over two decades she hasn’t changed all that much (the first book begins in 2001, the third ends in 2021). “She doesn’t become a philosophical person who thinks deeply about the world… she’s much more immediate and day-to-day and much more self-involved,” says Mohsin.

With Mohsin’s novels, that take jibes at leaders of all stripes, and mine humour from often tragic events, has she ever felt a need to hold back? Has she given offence? “Only once,” she recalls. It wasn’t a petulant politician but a disgruntled woman who “got very upset”, suspecting she was the butt of the Butterfly jokes. “The thing with satire is you have to make fun of yourself as well,” says Mohsin. She has filched lines from eavesdropped conversations and casual acquaintances, but much of the inspiration comes from within herself. “Butterfly is a true expression of my Hello-reading, self-absorbed, frivolous side exaggerated manifold,” Mohsin writes.

Butterfly might be Mohsin’s longest-running character, but she has also written a slyer political satire (The Impeccable Integrity of Ruby R, 2020), and a love story set against the 1971 war (The End of Innocence, 2006). Much of Mohsin’s work is set in Pakistan—a country she was raised in and frequently returns to.

As creative freedoms in the subcontinent seem to shrink, writers are increasingly facing strictures, bans, backlashes. But Mohsin says she has not had to self-censor. “I haven’t really but you know, the world is becoming more and more intolerant. And we’re living in a more polarised society,” she says. “I don’t badmouth people, it’s not personal. Public figures have to allow themselves to be commented on.” In the subcontinent, cracking a joke has become an act of bravery in itself as cartoonists and comics have faced the wrath of governments.

Mohsin and other Pakistani writers can no longer visit Indian literary festivals as easily, and the book trade between the countries has also suffered. “I find the increasing polarisation in both countries very disturbing,” she says. “Zia-Ul-Haq brought a strong religious element into politics and that in many ways undermined our polity. I hoped it would be different in India. Seeing it taking root in India has made me very sad. We’ve become mirror reflections of each other.”

Butterfly mulls precisely this question in her signature code-switching Butterflyspeak. “Some Indians I’ve seen on Facebook are saying kay haw, if we don’t watch out, we will also become like Pakistan. I think so they mean they will also start carrying leather kay Birkings and listening to Ghulam Ali’s ghazals and producing fast bowlers and thanking Gensaab. Chalo, it might make a pleasant change from thanking Moody all the time.”

MOHSIN BRINGS THE same sharp wit and keen eye to Browned Off, a podcast she co-hosts with UK-based editor Faiza Khan. The duo launched the podcast during lockdown, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement as publishing and other industries began examining discrimination and diversity. Mohsin and Khan were having similar conversations grappling with race and bias in writing and publishing. Over four delightful episodes they skewer western perceptions, exoticised diaspora writing, and British squeamishness about the help. Although it is on a hiatus, Mohsin hopes it can return soon.

In their inaugural episode they talk about the cultural expectations freighting non-western writers. Mohsin describes being at a literature festival once, and as the only Pakistani on the panel being asked about war. It was baffling. “I said I’m sorry I’ve never been a war reporter, I’ve never fought a war, unless it’s the battle of my bulge which is a continuing war on carbs,” she says, as Khan chortles.

But being a spokesperson for a culture isn’t new to Mohsin. “They will ask you about politics in Pakistan. They will ask you about what it feels like to be a woman in a country, which is going more and more towards the right. What did you think of 9/11?” she says. “If they are interviewing a British author, they wouldn’t ask them what they think about Brexit. But we are supposed to be commentators about everything.”

Mohsin is fed up with subcontinentsplaining—whether it’s religion, violence or simple words. In Tender Hooks (2011), also published in the UK, she had to avoid overusing Urdu but she also steered clear of exposition. “I didn’t go around explaining, what is a nikkah or what is dal. I grew up reading English books, when nobody explained to me what an eiderdown was or what a daffodil looked like. I just assumed this is a flower and an eiderdown must be something you put on your bed or you sleep under. You just get it, right? And you do a little bit of work and you learn. I don’t see why Western audiences can’t also do a little bit of work.”

In another episode the women discuss writing that pandered to the western gaze. Food is fetishised, for instance. “She hand-ground the spices, she crushed ginger in a pestle and mortar that belonged to her great-grandmother who had rescued it from a house which was set alight during the unrest of Partition,” Mohsin says, gliding into parody with wicked delight.

In our conversation, she bemoans some of the familiar traps South Asian novelists face. “Whenever you describe a scene on a street you have to talk about the open gutters, smell, the mangoes, the heat and rain,” she says. Or what about something as simple as a character describing their surroundings? “You don’t think, ‘that bedcover I got from Jaipur with the lovely flowers on it, is a Mughal pattern going back 500 years’. You won’t tell yourself that so why would you tell the reader that?” she says.

Mohsin points to the Nigerian crime caper My Sister the Serial Killer, a book she “found very refreshing”. “[Oyinkan Braithwaite, the author] just assumes that these are two sisters whose lives are just like anybody else’s. They’re not about tribal politics or race or about how the West looks at them. She just tells her own story. We are not given that kind of creative freedom.”

Mohsin has another comic novel in progress. It’s about desis in London, and she is at pains to reiterate it is “not about life in a corner shop in Britain” or “religion”. “I don’t even know where it will be taken because it’s a funny book. So in England, they’ll have to think about whether humour from the subcontinent is allowed. But in the subcontinent I hope it will come out.”

As for the Butterfly, she may or may not get the full-length book treatment again. For now, she flits around on Instagram. “I may carry her on there and see how it goes. She is definitely not dead. Maybe she’s in hibernation for a bit and will come back.”