Memory Keeper

Italicised words without footnotes or endnotes are often seen as alienating in longer fictions but this is the aspect I liked about Veio Pou’s debut novel, Waiting for the Dust to Settle. These words not only develop the reader’s curiosity but also push one to put in the effort to understand cultural difference and nuance. Patience can be a virtue here as we are dealing with a serious novel set in the armed resistance movements of 80s-90s Manipur. It narrates the events around Operation Bluebird (1987) when a counter-insurgency operation was led by paramilitary officers to retaliate against the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) rebel attack on the Assam Rifle’s Oinam outpost.

By now, there are a couple of English books describing the experiences of the Northeastern region under the shadow of insurgency—Bijoya Sawain’s Shadow Men, Aruni Kashyap’s The House with a Thousand Stories, Temsula Ao’s These Hills called Home, Easterine Kire’s Bitter Wormwood among others. Told with simplicity and a fast-paced linearity, Pou’s characters—particularly the protagonist Rakovei is instantly identifiable.

The settling of dust is both literal and metaphorical. Rakovei recalls how Senapati, his hometown, would see a deluge of army trucks on the highway followed by a cloud of dust. It was difficult to figure out who was chasing whom. The neighbouring villages would be filled with soldiers in no time. As a kid, he would fancy the green attire (‘treat to watch the army trucks’) and the discipline it embodied, only to be severely disillusioned later on. Intermediary solace is perhaps his grandmother who plays the oral storyteller tying the past and the present.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The harsh reality of having lost so many lives in the tussle between armed forces, Assam rifles and the armed secessionists of NSCN still linger. Moreover, the extra judicial killing orders, torture via electric shocks gave tremendous power to the men in uniform. According to an Amnesty International Report published in 1990, ‘The torture victims include older people, teachers, women who say they were raped and several dozen children. At least four children died in detention due to lack of medical care.’

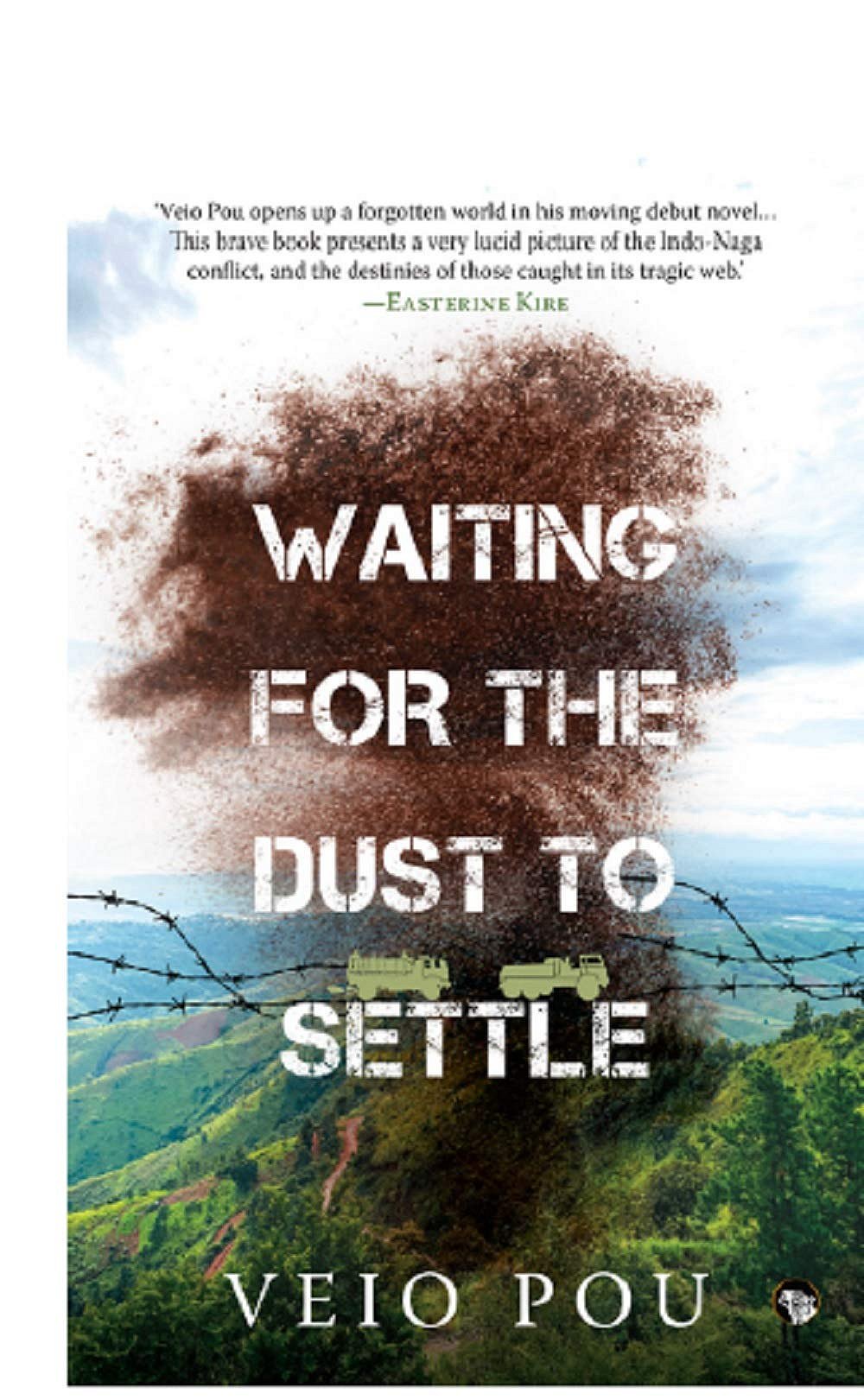

The novel’s cover aptly shows that it will engage with conflict in some form or another—the barbed wire, the army trucks against the background of pale blue-green hills—also suggest the significance of movement in the book. Female villagers in Oinam and Phyamaichi move with curved sickles to protect a woman from the armed forces in one instance. In another, a sudden order compels people in the village to rush to the church after their meal and keep their houses unlocked. (‘Soldiers had positioned themselves at all strategic locations to oversee people’s movement’).

But this book fails to become more than a descriptive account. The last few pages read very much like a newspaper report on the later 20th century events in Nagaland when the ‘hopes’ of a ‘Naga’ nation were fading away. Once again, the narration of these events of a ‘dark time’ in Northeast India in their attempt of being alternative, are beginning to look stereotypical. Even the comments of him being ‘chinky’ in a big city like Delhi and his detailed explanation thereafter about his facial/racial identity—repeated many a time even in cinema (think Nicholas Kharkongor’s 2019 flick Axone)—seem forced. This is not to say that these events needn’t be retold and recorded—but that it is time now to innovate instead of falling into older traps of the ‘mainlanders like to read about terrorism in the northeast’ or to keep explaining one’s identities as ‘Indian enough’ again and again.

Pou’s book is a sincere memory keeper although the reader is unable to seep into the whereabouts of the village and their intrinsic politics apart from feeling their grief. Warring sides are often not black and white but Rakovei’s disdain (and imagining of the ‘Naga imbroglio’ post these conflicts as a Mario Puzo’s film) is more of tragic despair than a steadfast zeal towards freedom from racism and mainland socio-cultural supremacy.