Memory as Metaphor

FICTION TENDS TO mostly discuss the partition of India in terms of its effects on the people of northern India; what happened to those on the eastern borders of the country is often ignored. But the strife, the anguish, and the displacement that happened in Bengal were just as appalling, and continued for many years after 1947. What is more, the partition of Bengal in 1947 had been preceded by an earlier, also disturbing partition in 1905; and, less than 30 years down the line, it was followed by the war that led to the formation of Bangladesh.

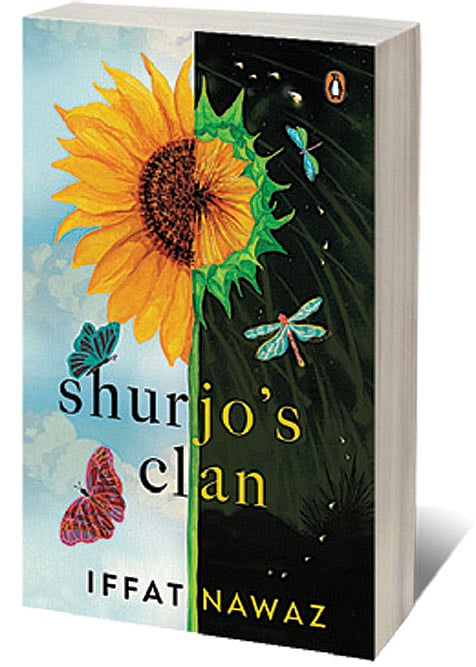

1947 and 1971 are, in a way, the basis of Iffat Nawaz’s novel Shurjo’s Clan. The ghosts (quite literally) of these two cataclysmic events form some of the major characters of the story. The protagonist Shurjomukhi ‘Shurjo’ grows up in a household dominated by the past: her grandparents came east during the Partition of 1947; her parents were born during the upheavals of a newborn East Pakistan. Shurjo’s father Babu lost his two brothers Shoku and Bhiku to the war; they were martyred in the tea estates of Sylhet, where Shoku was working when war broke out. Babu was the one who, travelling up to Sylhet, found their mutilated bodies and buried them. And who, every evening in his home now in Dhaka, hosts Shoku and Bhiku at dinner. For Shoku and Bhiku are part of the Unknown World, a realm bordering the Known World, and separated from it by daylight. Night falls, and Babu’s wife Bela, along with her mother-in-law Paru, prepares a big dinner to which come their guests: Shoku, Bhiku, and Bela’s long-dead mother Shantori, who had jumped into a well as a new mother. The family, both from the Known World and the Unknown, comes together every night to eat, and—more importantly—to talk. Her uncles’ and father’s reminiscences about the war, her family’s stories of the years gone by, shape Shurjo’s early years, filling her with memories that aren’t hers, moulding her mind, her beliefs, her sense of what it means to be Bangladeshi.

When Shurjo’s parents decide to move to the US in an attempt to shake Shurjo free of the ghosts that surround her—benevolent though those spirits be, much-loved and dear—life changes for all of them. For Babu, Bela and Shurjo far away in the US, and for those they leave behind, on both sides of the divide.

Shurjo’s Clan is an unusual example of magical realism: a story of the supernatural, but one crafted with so much heart that it becomes a metaphor. A metaphor of the memories Bangladeshis (and other nationalities, other ethnicities with a history of bloodshed and migration) might carry with them. Partition, the war of 1971, and the migration of Bangladeshis to the west form important pivotal points here, each contributing to the tension, the sense of both rootedness and of being uprooted, of fitting in and of standing out.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Interestingly enough, Nawaz does not go deep into the details of either Partition or 1971; both are mentioned briefly (Partition even more fleetingly than 1971), and in the form of quick snapshots of what Shurjo’s family experienced during these turbulent times. Only the far-reaching effects of these form the main focus of the novel, as Shurjo, growing from a young just-teen to a woman in her thirties, deals with her family’s past and her own experiences growing up as part of the diaspora.

Nawaz’s prose is lyrical, deeply insightful (especially when it comes to the nuances of being an immigrant), and moving. Her characters are believable, their stresses real, their sorrows and joys balanced. Shurjo’s story is an unusual coming-of-age tale: for its protagonist, of course, but also, perhaps, in a symbolic way, of Bangladeshis themselves. A coming to terms with the past, a settling into a modern skin.