Memories of a Fall

ON BOXING DAY, 2022, Hanif Kureishi’s life changed. A fall in Rome, in his apartment, would divide his life into a before and an after. After the fall his body would no longer heed his mind. The 67-year-old British Pakistani playwright, screenwriter, filmmaker, and novelist would become a playwright, screenwriter, filmmaker, and novelist who was wholly dependent on others, as he had lost all use of his limbs. But he did what writers do, which is to channel life into words. Unable to type, he dictated his moods and his thoughts to his wife and three sons. When his hospital dispatches first started appearing on social media and Substack, they quickly garnered an audience. Readers read his posts with a mix of fascination and dread, concern and curiosity. Here was a man, who in a moment, had traversed from the land of the well into the kingdom of the sick. And nothing would be the same again for him or his family. This was uniquely Kureishi’s story, but to be human is to know that illness and infirmity can (and will) besiege each of us and our loved ones. Illness both shrinks and expands one’s world, and Kureishi tells us just how.

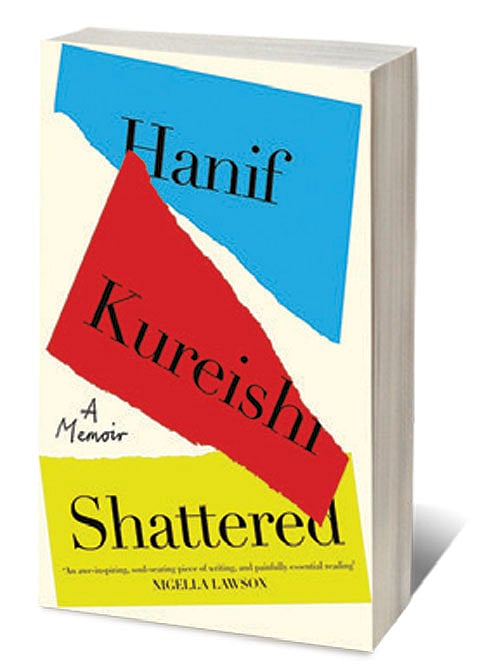

Shattered is an edited and expanded version of those hospital dispatches, written with honesty and humour. It is also a memoir of resilience of a man who two weeks after his accident would assert, “I am determined to keep writing, it has never mattered to me more.” The ‘writing’ not only allowed Kureishi to chronicle this time out of time, it was also his one way to assert his identity, as that of an author. As in the case of many writers, books provided an early escape in his childhood, “Once I could read I was free.” Reading and writing are twin and essential pursuits for Kureishi who spent his childhood discussing structure, ideas and characters with his father. He bristles at modern notions like ‘sensitivity readers’ believing that it is the job of an author to “smash the sea frozen inside us”. Reading gave him liberation, and writing an identity. By choosing to call himself a writer, he was also annulling the other racist epithets that had been hurled at him in the past.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Always interested more in the here and now, rather than magical elsewheres, he identified as a “realist” early on, and it is this realism that he brings to the memoir. His confessions can startle, especially when he talks about his childhood and how his mother was the “most boring person” he had ever met. His dispatches are not soaked in self-pity, but they do not brush over his frustrations or infirmities either. He writes of the long and lonely nights, when he is plagued by dreams and horrors. He doesn’t shy away from desperately dark moments when he is in despair and even longs for a quick release. He wishes he’d been kinder, and strapped to his bed he begrudges the happiness and health of others. He must rely on his family for everything, from brushing his teeth to scratching an itch. This changed balance of power and responsibility stretches them all, and especially his wife Isabella. The dependency riles him, but he also seeks solace in the stories of other patients, those like Miss S, who he meets when she is in a wheelchair, but when she’d first came to the hospital all she could move was one eye.

He writes of the Italian nurses and doctors who treat him with care and respect. Nurses who sing and keep their cheer even while cleaning human waste. As a writer he is always invested in the lives of others, and cares to learn about those tending to him.

Early in the memoir, Kureishi writes, “When you are writing a book, the main purpose is to delight the reader: that should be the focus of the work.” In Shattered he executes his own mantra by giving us a memoir that tells us of a man who had a great fall, who realised “there could be no progress without failure” and who puts his broken body together again, word by word, sentence by sentence.