Mayhem in the Metropolis

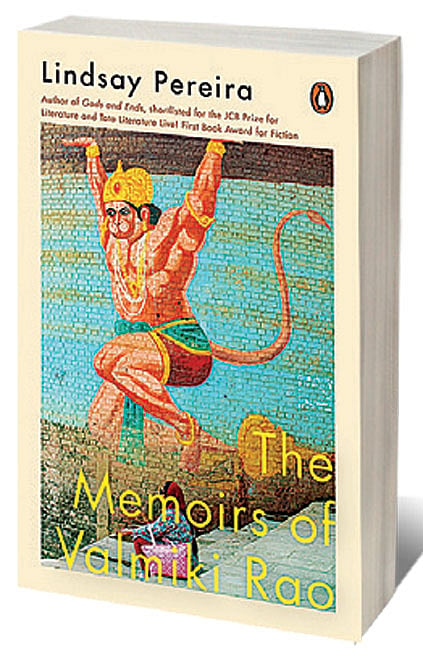

THE TITLE OF Lindsay Pereira’s new novel, The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao clearly suggests what it’s going to be about or, at least, the story that it’s going to tell. But rather than a full-blooded version of the Ramayana, we get an elegy to a city wilfully destroyed by greed and cynicism, a lament to dreams that died and people that were murdered, a dirge that mourns the concerted dismantling of systems of thinking and being that upheld tolerance and compassion.

Reminiscent of Kiran Nagarkar’s Ravan and Eddie and Rohinton Mistry’s Tales from Fiozsha Bagh, Pereira’s Bombay novel opens in the teeming, overflowing, bursting-at-the-seams Ganga Nivas chawl in Parel, a building inhabited entirely by working-class Hindus, secure in the rhythms and routine of their individual and community lives. Small rooms, common toilets and shared balconies ensure that secrets are few and that whispers abound, but there is little that will disturb the equilibrium of the chawl and its residents.

Valmiki Rao, a retired postmaster, lives alone and trades news and nostalgia and the ailments of his ageing body with his old-men friends. Around them, families expand and contract as children are born and marry and sometimes move away, elders die and another generation ages to take their place. Vishnu and Kashi are an unusual couple among the residents of Ganga Nivas who are mainly worn down by the struggle to survive in a city that takes as much as it gives — they seem to love each other and radiate joy and hope. Their boys, Ramu and Lakhya, are bright and helpful, rays of sunshine in an otherwise physically and morally grey world. On the other side of the building lives Janaki, as lovely and unlikely as a lotus that emerges from a muddy pond. She is admired by everyone but loved by Ramu, who has grown into a charismatic and widely respected young man. Sadly, Kashi dies young and a devastated Vishnu is married off again to start a new family even as he drinks himself to death. Ramu and Lakhya are effectively abandoned and soon, Ramu joins the aggressive and parochial Shiv Sena, not for their divisive ideology but for the slim hope of a secure future that they hold out to the men who have been pushed to the margins of their natal city.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Across the street is Sri Nivas, a sibling of Ganga Nivas, perhaps even its identical twin, with its own heroes and villains, its favourites and its bullies, its angels and demons. A young man from the south, Ravi Anna, rules the roost, standing up to the Shiv Sena, but building his own gang of rowdies and goons.

The city roils around these settlements, playing out its own rivalries and alliances, like a river that eddies and turns to sludge as it collects more and more debris and then, flows free again. But far away, in an obscure northern town, a mosque has been demolished by a group of angry young men fired by the righteous claims of retributive history. In a matter of hours, the war for the soul of a nation has spread across the country and arrives at the gates of Ganga Nivas and Sri Nivas, already seething with their own love triangles and petty jealousies and the high emotions of their carrom and matka-breaking competitions. Valmiki Rao chronicled the events of the day that changed the city and what happened in the bloody weeks that followed, an account that he now shares with us, unknown readers situated in a future that is reaping the whirlwind of that long ago December.

Valmiki Rao carries forward many of the themes from Pereira’s earlier novel Gods and Ends. But this time, there is an urgency to his writing — he persuades us that Valmiki Rao’s narrative is both a memoir and a prediction.