Margaret Atwood: The New Testament

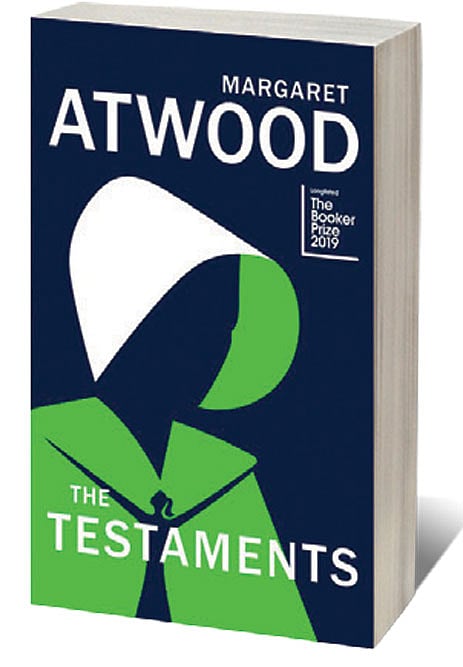

WITH OVER 125, 000 copies sold in the US and two reprints in its first three days, The Testaments (Chatto & Windus; 419 pages; Rs 799) by Margaret Atwood, the celebrated Canadian author’s sequel to her 1985 cult classic The Handmaid’s Tale, is the neon-green publishing event of the year, dominating bookstores (100,000 and counting in the UK) and book news. The story of a young woman enslaved by a Christian fundamentalist regime which comes to power in the US after a fertility crisis, the Republic of Gilead, the novel is a feminist and libertarian touchstone which has stood the test of time. Booker Prize-winning Atwood (who, at 79, is once again in the running for the prize) earned multiple accolades for the book which poured out from yellow legal notepads onto a German manual typewriter in West Berlin with the spy whispers and sonic booms of the era echoing in her ears, already with a life of its own; it was adapted into a film (1990), an opera (2000), a television series (2017) and studied at universities. It joined the canon in the way of George Orwell’s own warning against totalitarianism, 1984, which turned 70 this year, and like that book, was revived after the Trump victory; women began to protest criminal abortion laws in the US using the red robe and white wings of the handmaiden, as they have in Argentina and elsewhere.

For the uninitiated: The Handmaid’s Tale records the testimony of Offred, trapped in her Handmaid’s red robes and ‘wings’ (large, white bonnets), which mark fertile women who exist to bear the children of a cruel and mostly barren elite: Commanders and their blue-clad Wives. Offred—off the patronymic formula which names women according to the man they serve—is covertly courted by both the Commander, who seeks evidence of the desire he has helped purge, and his driver, Nick, a mysterious man who she herself begins to desire physically and romantically, while knowing next to nothing about him. Not even, at the end of the book, if he will deliver her back to the complicated independence of the free world or into the hands of the republic for their crimes of passion, carrying the beginning of what he believes may be their child. Who wouldn’t want to know what happens next?

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

To that end, 34 years later, fast-paced and full of fire, The Testaments is an enjoyable, compulsively readable exercise in wish-fulfillment, taking us 15 years forward. Most wonderfully (spoilers ahead), through the freedom and reunion of Offred’s daughters—one, Agnes Jemima, from Offred’s previous life with her husband Luke, raised in Gilead, and the other, Daisy or Nicole, the child that was presumably Offred and Nick’s, raised in Canada by a couple who are part of the May Day movement—as well as the redemption of formidable Aunt Lydia. One of the women who trained Offred at the Red Center, the chief bane of every handmaid’s existence, now reigns at Ardua Hall, from where she writes a ‘holograph’ that runs parallel to Agnes’ and Daisy’s informative but less compelling stories. In this split narrative, Aunt Lydia is the most fascinating subject. Revelations of her former career as a judge and her own torture at the hands of Bad Santa-like Commander Judd open up this complex villain. What’s more, the two daughters even bring down Gilead, find their mother and make us believe in womanly solidarity again as it becomes clear that Aunt Lydia was taking the long view to explosive vengeance, boiling over when whatever was best about Gilead (her ‘freedom from’ not ‘freedom to’) is corrupted.

Aunt Lydia supplants Offred as narrator to tell us how Gilead came apart and how we are all just a step away from complicity; how she helped pull down what she was forced to help put up, in the only kind of redemption you can attempt once your hands are dirty; and, importantly, how we can never be sure that the next regime is going to be better than the current one, given human nature. ‘The corrupt and blood-smeared fingerprints of the past must be wiped away to create a clean space for the morally pure generation that is surely about to arrive,’ she states, straight-faced, quipping, a second later, ‘Such is the theory.’ It’s a rare moment of wit for a woman who has a statue of her standing while she is still alive, which she is in turns amused and inspired by.

Aunt Lydia has returned to the light partly because there may finally be nowhere left for her to turn. ‘I’d been in tight corners before. I had prevailed. That was my story to myself,’ she tells us of her initiation into Gilead, in an unconvincing excuse for the system she brings into place; how does a woman who once believed in ‘life, liberty, democracy and the rights of the individual’ justify instituting a system of cattle prods and floggings? We don’t quite see this transition from the woman full of rage against the system to the indoctrinator spouting fading platitudes. The television version, while clichéd, is almost more convincing, with its depiction of her sexual humiliation and disapproval of the failure of the modern family unit as the context to her cruel regime (admittedly crueler than in the books—the TV series is altogether a different creature).

Sadly, this new book, satisfying as it sometimes is, lacks the wise, wicked voice and nuance that set The Handmaid’s Tale apart, and not just because of the challenges that most sequels face; of not living up to the original or of performing too much happily-ever-after. As an annexure, The Testaments is successful in giving us much-craved detail, in filling in what we lost between the gaps, but it hasn’t given us much depth. The deft, wry one-liners Offred delivers are far superior to Aunt Lydia’s blunt, stoic delivery, as delightful as it is to get inside her head. And the air that first book had, of parable and oracle and fairytale all rolled into one, years after Angela Carter’s feminist magical realism had been unleashed (notably her collection of short stories based on fairytales, The Bloody Chamber, 1979), is altogether of another world, of course. But today, what we need is a call to arms—so Atwood, hopefully as prophet, she has enacted an uprising by both liberals and collaborators. As she says in the new book’s acknowledgements, ‘Totalitarianisms may crumble from within... or they may be attacked from without.’

IF YOU HAVE been watching Hulu’s television series—adapted from The Handmaid’s Tale in a glossy, horror film version of the book told in a post-racial version of our current moment, complete with an uplifting soundtrack—this new book is, in a sense, a continuation of the story the series told in the interim, over three interesting if problematically different seasons. Among the many departures from the original are the transformation of the Commander’s wife Serena from elderly, arthritic woman to an attractive and sometimes sympathetic woman of the same age-group; Commanders and particularly handmaids of all races populate the TV series, while the book’s White supremacist Gilead sends people of colour off elsewhere, to an uncertain doom; Nick is a sweet, sacrificing romantic object instead of a sexy, cynical-seeming man she can’t read and Offred is now a feisty renegade, not the ordinary woman we met in the book. This is the modern world The Testaments responds to; one in which the gaps between genders and races have been reduced, but not satisfactorily. It returns to the exoskeleton of its story because our current moment requires it.

For, the label of science fiction—one Atwood has rejected—helps the book function as a Trojan horse of sorts. If people are pulled in by the world of pugilistic Aunts and menacing Eyes who train and monitor handmaids even as they are envied by subservient Marthas and lower-class Econowives, they will be reminded of Atwood’s warning even if they miss other ones: the damage extremists can wreak.

It is remarkable how many people remember the framework of the universe of The Handmaid’s Tale over the rich personal narrative that transcends its trappings, one which enchanted many a reader at the time. As Charlotte Newman remarked, when the world celebrated 25 years of the book, it was lifted by ‘Atwood’s lyrical prose, in which facts appear to merge into one another, and history appears immaterial; Offred is kept alive by her inner life, and reality and history become a kind of symbiotic mirage’ (The Guardian, 2010). This is the book we remember, decades later, as much as the iconography of handmaid hell captured our imaginations—and the awful image of a woman being held down by the wife of the man who will rape her. In many ways, The Handmaid’s Tale is the natural successor of Atwood’s impactful first novel (Atwood has since published more than 50 books), The Edible Woman (1969) about a woman who refuses to be consumed by society and her fiancé; she offers the latter a cake in the shape of a woman, in the penultimate sequence, refusing to be devoured.

In 1985, The Handmaid’s Tale was assimilating the many changes that had come with women’s liberation, and the many conundrums born thereof. Atwood was commenting on the same trap of the body in both books, extending the biological conundrum: as long as only women can have children, we may struggle to find true equality. The truth is, the author was speaking of the times she lived in, not the future—it is just frightening and tragic that her message speaks to today.

We may forget that Gilead’s extreme atrocities, as Atwood has repeatedly stated, all have a historical precedent, while calling the book, in her 2017 introduction to Vintage’s repackaged publication, an ‘anti-prediction’—‘if this future can be described in detail, maybe it won’t happen.’ Reading it now, in 2019, is to understand just how much we have fallen short of the promise of past victories.

‘IN THAT VANISHED country of mine, things had been on a downward spiral for years. The floods, the fires, the tornadoes, the hurricanes, the droughts, the water shortages, the earthquakes. Too much of this, too little of that. The decaying infrastructure—why hadn’t someone decommissioned those atomic reactors before it was too late? The tanking economy, the joblessness, the falling birth rate,’ Aunt Lydia says in The Testaments, reminding us of the context of Gilead. ‘People became frightened. Then they became angry. The absence of viable remedies. The search for someone to blame.’ She could be talking about the refugee crises in the Western world and the dictatorships of strongmen sprouting everywhere, the lynching of minorities and the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir in India. The 21 million women mysteriously left off our electoral rolls, the women whose rapes go unpunished while people are punished for harming cows, the women who still have to worry about what they are wearing or what time they get home.

‘It’s strange to remember how we used to think, as if everything was available to us, as if there were no contingencies, no boundaries; as if we were free to shape and reshape forever the ever-expanding perimeters of our lives… Luke was not the first man for me, and he might not have been the last,’ Offred says in The Handmaid’s Tale. She expands on memories of her old life, and how modern, liberated women had to provide for the possibility of rape on the streets and the threat of resentment of their lovers at home, as well as the hope that this one, at last, would prove to be the man who proved beyond reproach.

Offred’s poignant fears shadow her narrative—as much as the book is about women’s rights to autonomy over their minds and bodies and the threat governments, men and other women have posed to them, it is about the threat within; the threat posed by love of the opposite sex, even by Better Men. In some of The Handmaid’s Tale’s most moving passages, she talks about this range of responses to men; one which is mirrored elsewhere in the book when she has sexual thoughts about the men who manacle her and sympathetic urges towards the Wife who has her in her talons. Atwood was exploring complexities beyond the purview of Stockholm Syndrome, even while she explored how it enables an Offred to survive; Gilead reduces environmental pollution—while creating a deadly dictatorship which kills women’s rights. After MeToo, it would still be interesting to have her explore more of this grey by finding Offred at the end of The Handmaid’s Tale, in that ominous van that takes her to Canada but we are not sure to what kind of freedom; another journey which would take us back to the future.