Man of the Peaks

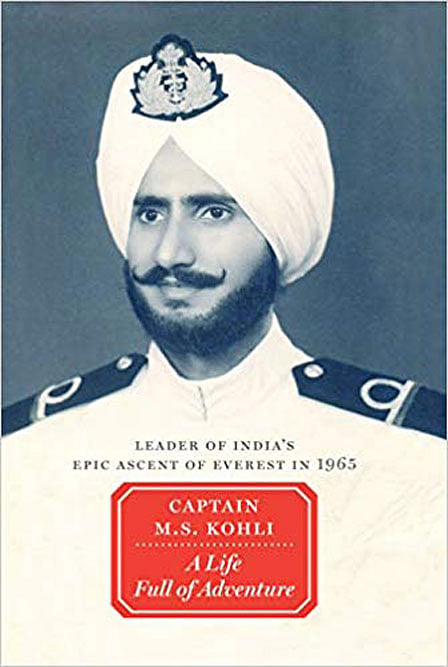

There was a time when Indians were considered to be pioneers of mountaineering. This was back in the 1960s, when adventure had a different meaning, and climbing mountains was far from the commercial enterprise that it has transformed into today. The highlight of MS Kohli’s book, A Life Full of Adventure talks about those heady days.

After Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay ended the race for Mt. Everest in 1953, two expeditions—the Swiss in 1956 and the Americans in 1963—followed in their footsteps and found success. The Indians weren’t far behind. Though there were first ascents being made on peaks in the Indian Himalaya, it wasn’t quite like the glory that came alongside climbing the highest mountain in the world.

Kohli’s book is key, considering that he was at the heart of these events, even though his journey started out in the most unlikely of places. He soon found himself a part of two unsuccessful attempts on Everest in 1960 and 1962, embracing his fair share of dangers in the world of ice and snow, high up in the Death Zone. Bad weather forced them to abandon the first, while the second attempt fell short by a mere 300 feet from the summit. The team may have returned empty-handed on both occasions, but Kohli had already made his mark as a promising young climber of that generation.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

Besides getting high up on Everest, he had also led a team on the first ascent of Annapurna III (7,555m) in between the two attempts in 1961. Given just what was at stake during their third expedition in 1965, Kohli was now handed the critical role of the leader. Fact is, he never made it to the top of Everest in his lifetime. But he eventually led what was the most successful climb up the mountain at the time.

By the end of that summer, the Indian team had managed to put a record nine climbers on top of Everest. Never before had three men stood on the summit together, while Nawang Gombu became the first man to scale the mountain twice. While it placed India firmly in the limelight, life had come a full circle for Kohli since his days as a young boy, scrambling up the Kaghan hills around his hometown of Haripur, which today lies across the border in Pakistan.

While growing up, Kohli had soaked in his early adventures in the volatile landscape of the Hazara district in the North West Frontier Province. One of the first climbs that he made was on his father’s shoulders as a three-year-old during a pilgrimage up Martyrs’ Summit—a hill in the vicinity of the family home. And right since those early days, he had learnt the art of facing adversity—whether natural or manmade—and overcoming all odds.

By the time Partition reared its ugly head and led to the birth of Pakistan in 1947, Kohli was writing an epic of his own. The family was forced to flee their home, as mobs went on a rampage in his neighbourhood. On another uncertain train journey from one refugee camp to the next, Kohli survived a barrage of gunfire, lying among the dead until help arrived. Though they finally made it across to India, they now found themselves in a strange land with no place they could call home.

While starting life afresh in this new land, the wanderings eventually took Kohli to Delhi, where they decided to start life afresh. His leadership qualities were evident even during those early days, whether it was as the captain of the college hockey and football teams, or as president of the students’ union. Work life handed Kohli the opportunity to join the Indian Navy, which turned the tide in his favour, taking him back to his beloved mountains.

On his first Naval posting in the hill town of Lonavala, that passion was stirred yet again after all those years. He was soon learning the finer nuances of climbing, as he scrambled up the many mountains of the Sahyadri range.

It was only in 1955 while taking on the Amarnath yatra, that Kohli had his first brush with the high mountains. He was soon a regular member of Navy expeditions to the Himalayas and established himself as one of the top mountaineers of India. The epic of 1965 was the culmination of his exploits that firmly embedded him in mountaineering history.

On his return from Everest, Kohli took on a mission of a different kind in the Indian Himalayas. It was a time when China was conducting nuclear tests in the Xinjiang province. To spy on their activities, the Central Intelligence Agency collaborated with Indian authorities to plant a spying device on top of Mt. Nanda Devi (7,816m)—the highest mountain that is completely in Indian territory and just across the border from China.

The secret operation was a landmark back in the day. The mountain had its own history of denying a number of climbers their attempt to get to the top. Then, to carry an electronic device to the summit was unimaginable. Though the team managed to haul it all the way to summit camp, when the weather turned, they were forced to stash it on the mountain and beat a hasty retreat.

The following season when they went back up, the device had disappeared. What was a major cause for concern was the missing radioactive component that was to power the device, which was fodder for environmental speculations and caused a political uproar in the years to come. Though the device was eventually planted on other mountains, it was nothing quite like the drama surrounding the Nanda Devi story.

After close shaves on multiple occasions, Kohli brought an end to his mountaineering career, and went on to hold important positions at the Indo-Tibetan Border Police, Air India and the Indian Mountaineering Foundation. Here too, he registered many firsts against his name, though the narrative appears to be nothing more than a tedious documentation of scattered memories.

While the book is important as a chronicle of Indian mountaineering, and the life that Kohli has led is nothing short of a blockbuster film in waiting, the commentary can get insipid at times. The achievements may look impressive on a resume, but the book often fails to deliver them. For those interested in mountaineering, it is certainly an engaging read.