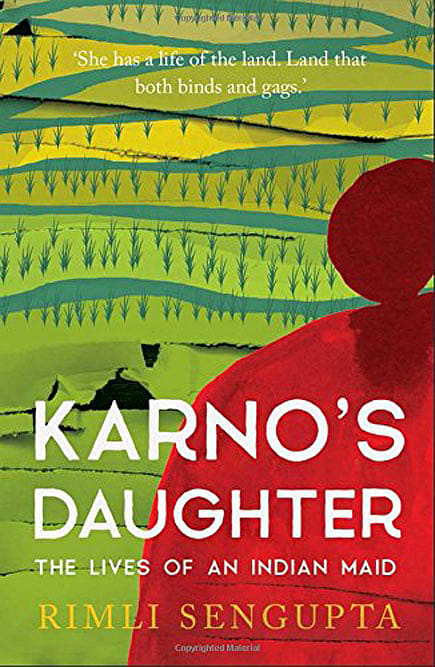

Maid in India

'If I can't have it, so can't you,' is the typical crab mentality that best defines the rat-race for house help in India. And Rimli Sengupta's debut novel Karno's Daugher operates on these metaphors throughout. A crab isn't something that the central character of the book feasts on with her family, it is much more. It emerges as a strong narrative tool that digs its tentacles into the victims in a vicious way. Just as her name, Buttermilk is a reminder that while the domestic servant does all the hard work, the cream is churned out by the urban elites in a post globalised world. Buttermilk's story, though not a memoir, is similar to Baby Halder's Alo Andhari that touched me in its translation. Baby had mentioned in her last pages that even Ashapurna Devi (a reputed novelist) would write after finishing all chores, it inspired her to continue writing in her own words. Buttermilk, however, has practical ambition; she has learnt the hard way to live with stagnant policies of the state for domestic workers. Sengupta is her mouthpiece in the book, a conscious one, and that's a good thing because she acknowledges the limitations of representing Buttermilk right at the start. Haven't we had too many urban elite women speaking and posturing sympathetically for the maids already?

A year ago, Zohra Bibi, a part-time maid hailing from West Bengal was the target of much abuse online as well as offline thanks to the Moderne Mahagun incident in Noida. Many had alleged that vices like greed and malice comes naturally to the domestic labourers. Hence, a good way of keeping that in check is by maintaining low wages; reportedly Bibi's case was one of stealing money from her owner. The discrimination that domestic workers face is not only on the economic level, it is very much ingrained in the psyche, a form of a caste system, and indeed, the products of it too. The physical description of Buttermilk reflects all of that quite perceptively: 'Her hands are a scrapbook of scars. Her knees have fleshy back calluses from decades of swabbing floors on them.' But as they say, scars too have stories to tell. Buttermilk used to have dreams of her own before she had migrated to the city for work. The author takes us into her childhood and how an inescapable, rampant cycle of land oppression, sibling rivalry and bad marriages sealed her fate forever. The larger context is, of course, how the map of Bengal changed with the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation war and the chaos that came in the aftermath.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Though Buttermilk isn't that educated, she narrates the uproar in her village then, with somewhat naive but eidetic memory. She is a survivalist in the truest sense of the term. She had the right justifications for giving in to the lure of free food, free toilets as assembly elections approached. 'Now, Trinamool is giving, why shouldn't we take…? If another party comes later, and they hand out toilets, we'll take theirs too…' What is also remarkable in her account is the kind of caste attitudes she's navigated post the war, becoming both a victim and a victimiser. She also becomes a typical mother-in-law herself despite going through that ordeal once. She pressurises and convinces Rupa (her daughter-in-law) that only a child would fix her drug-addict husband. Even when she does manage to own land, however little, she doesn't easily let go of the harshness that comes out of poverty. The book takes acute note of these particulars and connects them with larger political changes. For instance, the immediacy with which the labour class hurriedly get their Aadhar cards afraid of being left out of governance is a genuine concern. As surveillance technologies like Aadhar and NRC change back in my home state Assam, domestic labourers face a familiar (though largely overlooked) crisis.

Nowhere does the book suggest that nobody requires domestic help, but it is critical of the unavailability of laws to protect the rights of maids. In fact, the author is quite dependent on her ('Simply put, Buttermilk makes my life possible. For this, I pay her a monthly salary that just about covers dinner for two at a nice restaurant.'). At one point in the book, we are told that 'Every urban home in India has a Buttermilk'. From Baby Halder to Sapna (in Prayaag Akbar's Leila) to Sengupta's Buttermilk, maids in the literary imagination are constantly willing to break boundaries. Till the barriers break at our domestic spaces, their war is far from over.