Lion’s Share

AS A YOUNG FAN of cricket— and one would imagine for anyone who was a fan of the sport—watching Sri Lanka deliver one exquisite performance after another at the 1996 World Cup held in the subcontinent came as a matter of great surprise. Nobody fancied Sri Lanka. In cricketing terms, they were still outsiders; they weren’t so much as considered dark horses for the tournament. Their status was no doubt belied by some of the performances they put up in the lead up to the World Cup, including impressive victories in Sharjah against Pakistan and the West Indies. But there was also the political turmoil that the nation was facing that was to be reckoned with.

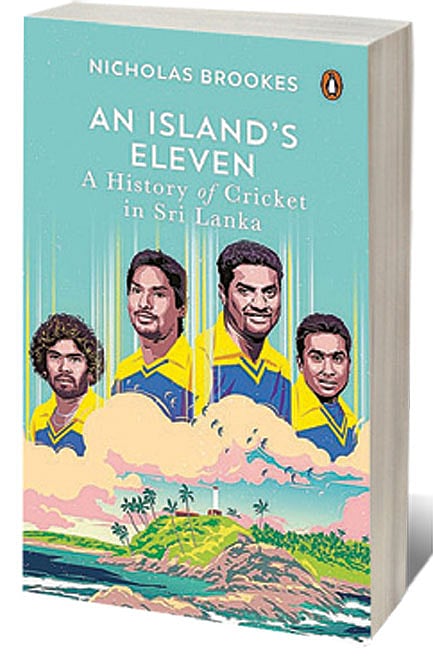

As Nicholas Brookes writes in his new book, An Island’s Eleven: A History of Cricket in Sri Lanka, “Sri Lankan cricket was in the doldrums. The board was broke, with as little as $5,700 in its coffers. Months before the World Cup, oddsmakers gave the team a one-in-sixty-six chance of lifting the trophy. Most felt the tournament would bring inevitable humiliation. Once it was done, it would be a struggle to attract sides to war-torn Sri Lanka.”

How then did they manage to win the Cup? We know they had Chaminda Vaas and Muttiah Muralitharan putting the squeeze in on sides batting first; they had Sanath Jayasuriya at the top of the order invariably allowing their chases to get off to a flier; they had Arjuna Ranatunga’s magnetic leadership; and more than anything else they had the hitherto unrealised genius of Aravinda de Silva, who, in the final, battered the Australian bowling in a virtuoso performance of some note. But, still, given the odds, given where Sri Lankan cricket was, the victory wasn’t merely a surprise. It was a shock and befitting of their nickname the Lions.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Brookes’ book tells that tale and more. Sri Lanka’s cricket history is long and complex. The region’s earliest recorded match dates to 1832, when there were calls in The Colombo Journal for the formation of a cricket club. A journey, which began then, and which took until 1981 for Sri Lanka to achieve the status of a Test-playing nation was marked by a growth fuelled by club and school culture—this was entrenched by the role played by the colonists, but also by resistance against colonialism.

In that, several individuals played a critical role. An Island’s Eleven chronicles this story. It tells us—in a narrative filled with anecdotes—about the more recent characters who have shaped Sri Lanka’s cricketing story: the roles played by Kumar Sangakkara, Mahela Jayawardene, Aravinda de Silva, Muralitharan, and, most importantly, Arjuna Ranatunga. But it also goes back in time to expound the roles played by lesser-known individuals. For example, “the island’s first working-class cricketer,” MK Albert, who moved from being a grounds boy at the local club, helping lay the matting wickets, to one of the region’s top batters. Together with “Chippy” Gunasekara, Brookes says, Albert pioneered an unorthodox approach to the sport, calling ones and twos in Sinhala and having the opposition doing the running around.

“Whether they knew it or not, it was a political act of self-identification,” writes Brookes. “And in breaking the stranglehold of the Colombo middle class, Albert became more than a cricketer. For most of the ’20s he was Ceylon’s most reliable run-getter, and a powerful symbol challenging the class boundaries, which so rigidly segregated the island.”

In recent years, we’ve seen a burgeoning in cricket history writing. From Prashant Kidambi’s magisterial Cricket Country: An Indian Odyssey in the Age of Empire to Osman Samiuddin’s The Unquiet Ones: A History of Pakistan Cricket to Peter Oborne’s Wounded Tiger: A History of Cricket in Pakistan. Brookes’ book adds to this rich collection. The writing is a product of scholarly learning and research. But it’s also a tale told with love and affection, for Sri Lanka, its people, and its cricket.