Ladies of the Land

ONE OF THE big news stories that came out of Maharashtra in 2009 was about a leopard called Ajoba (‘grandfather’ in Marathi). This big cat travelled 120km from Malshej Ghat, Junnar and made a “leopard-line” rather than a beeline for Sanjay Gandhi National Park in Mumbai. Readers were charmed by this “gentle old cat” who crossed two wildlife sanctuaries, a busy highway and a railway station, to reach Mumbai. It also raised the possibility that the leopard was determinedly returning to its original home after being released in Malshej. The reason we know so much about his journey? Ajoba was part of the first ever radio-collaring project on leopards. Vidya Athreya, the biologist who worked closely with the Maharashtra Forest Department for this, has since implemented numerous innovative ideas on understanding leopard behaviour near human settlements.

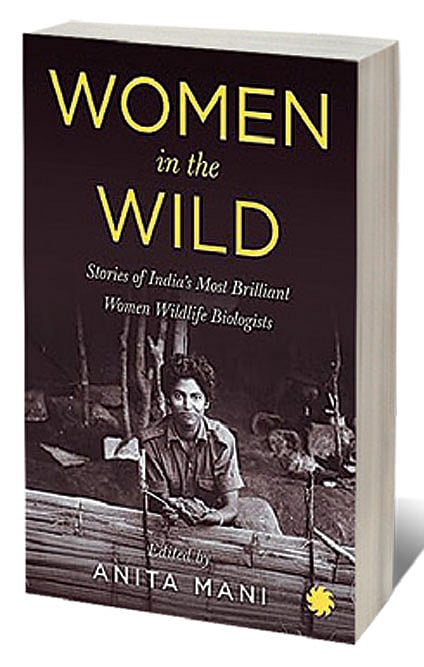

When you begin to read a book with words like ‘women’ and ‘most brilliant’ on the cover, it primes you to expect inspiration from the achievements of the subjects.

You expect to read about the mountains they scaled, and vicariously appreciate and delight in the views from the top.

But this book does more than that.

It introduces the reader who is not yet aware, to the kind of research and conservation work happening in the country, conceived and executed by these remarkable women. It shows us how different practices are changing the way conservation is done, be it Uma Ramakrishnan’s path-breaking work on tiger genetics, Divya Karnad’s understanding of fisheries, Divya Mudappa’s restoration work in Valparai, Nandini Velho’s work with memory projects, activism in Arunachal Pradesh and Goa, or Pooja Choksi’s work with bioacoustics to answer questions related to ecological restoration. Usha Ganguli-Lachungpa written by Teresa Rehman takes us to the high-altitude mountains and Ghazala Shahabuddin written by Neha Sinha shows the secrets of the oak forests. Purva Variyar rounds up younger researchers who are embarking on new journeys.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Through their work, the book talks about their work, it takes us across landscapes and coastlines, introducing us to plant species, animals, communities, and the solutions that these women are attempting for the many conservation questions. This is important because so much of our written history has missed mentioning stories of women like these.

Jamal Ara’s story is an example of this. In a brilliant essay that reads like a mystery, Raza Kazmi uncovers clue by clue in pursuit of India’s first Birdwoman. Based out of the Chota Nagpur plateau, Jamal Ara wrote about her research for 40 years, but is still “arguably the most mysterious figure in Indian ornithology.” Jamal Ara’s life was turbulent. Her husband left her and their daughter almost homeless and without support, just a few years into their marriage. Ara’s journey back to solid ground and her tremendous passion and dedication to conservation is told lovingly to Kazmi by her daughter. She was 26 when her first paper appeared in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (JBNHS), the first comprehensive account of the status of wildlife in Bihar. She wrote for journals, worked on translations, did a pioneering show on Akashvani called ‘Prakriti ki God Mein’ and even had her work presented at an international conference in 1949. All this and more when the conservation world had very few women sharing the stage with men, especially going on field and doing research.

The book also tells us a little something about coping. As a writer, and a reader, as I move through life collecting experiences, I am interested in how human beings (especially women) cope. How they deal. How they navigate vulnerabilities and uncertainties. The hacks they use. How they survive, and how sometimes, despite everything they cannot. But what is commendable is that these nuances are interwoven in the essays, they are not the story. It dispels a concern I had before I started reading the book. The stories are not about their trials as women; the essays speak of their work, their passion, who they are as biologists and how that translates into their lives. Mani ensures you stay with the core of the stories, which is the women and their work. The rest is for the reader to read into, and between the lines. That is why these stories stay with us. Our own blueprints are strengthened by these nuances.

In that, Viji’s story, written by Zai Whitaker, has my whole heart. Viji is J Vijaya, India’s ‘Turtle Girl’, one of the country’s pioneering female herpetologists. Her work and research on the killing of Olive Ridley turtles led to the then prime minister, Indira Gandhi, to ban the turtle trade. She also re-discovered a species that was thought to be extinct — the Cochin Forest Cane Turtle (and it was named after her: Vijayachelys sylvatica).

Viji’s face smiles at you from the cover. Her arresting expression tells you a bit about what you will read in chapter two. That along with her passion for work, Viji tried to live in a way that was as true to herself as possible. Of course, she worked hard, and unabashedly — be it collecting “stinky” crocodile scat (and commuting with it), writing about her findings, taking detailed notes on field, or studying away from home. But Viji also showed her disdain of humiliating school practices that were all about marks and ranks. She stood up to (and slapped one, too) the rowdy eve teasers who harassed her on her bus commute in Chennai. At age seven or eight she witnessed her mother succumb to schizophrenia and, along with her two supportive sisters, “transformed herself into a bulwark of strength that protected her mother”.

Viji’s story, like so many others in the book, and outside of it, is an emotional roller coaster with celebratory highs and difficult lows, and when her story ends, it makes you pause, put away the book for a few moments before you start on the next chapter.

Both Uma Ramakrishnan, written by Prerna Singh Bindra and Vidya Athreya, written by Ananda Banerjee talk about the need to communicate science, research and emotion to people outside the realm of wildlife. Vidya’s work with citizens, journalists, forest departments and police outfits has gone a long way in mitigating conflict between humans and leopards.

Outreach is key, and being excited about your subjects only helps draw in more people. In a fraternity of scientists where emotional attachment to work or subjects are discouraged, even criticised, some of these women wear their heart on their sleeve in terms of the landscapes they are working in. There’s a quote by Uma which captures this, “Why should I let others define who I should be or apologise for who I am?”

To come to a few of the things that perhaps could have been better. As a read, the anthology, like so many others, is uneven in its writing, with some chapters being written more powerfully than others, which is perhaps why it might have needed crisper edits in some places as well. This is an important time for communication and outreach about wildlife and conservation, and books like these should reach far and wide. In that, perhaps we could—as a community of communicators—think more deeply about the use of different formats and elements in our books to reach audiences who are beyond the fraternity that already know the subjects well.

I hope it travels to people who should read it. As Mani says, while it is difficult for women across fields of work, conservation comes with its own set of unique challenges. Divya Mudappa, written by Shweta Taneja, says of conservation, “a constant struggle of swimming upstream in a river filled with sand,” and then of conservationists, “we fly on hope.” This is what we take away, then, remembering that even in spaces that were both physically and mentally difficult, they made space for themselves at the table.