Kunal Basu: Our Brave New Worlds

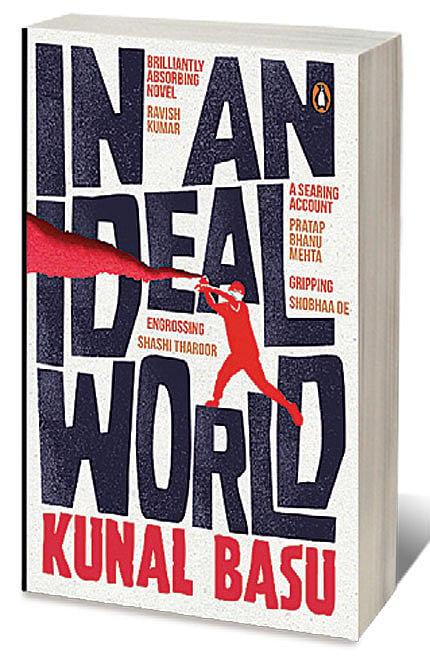

ONE OF THE major questions of our time is, what kind of society are we becoming? Noted author Kunal Basu’s latest novel In an Ideal World (Viking; ₹ 599; 208 pages) is an exploration of this question and an attempt to understand why it needs to be asked. Basu, who is the author of seven novels and a collection of short stories in English, four novels in Bengali, teaches at Oxford’s Said Business School. His writing explores ideas and dilemmas that confront all lives. Starting from his debut novel The Opium Clerk, (2001) set in 1857 Calcutta, and irrespective of whether he is writing in Bengali or English, historical or contemporary fiction, Basu looks at, “complexities in our society which we need to address with respect and sensitivity”.

In an Ideal World is set around a Kolkata upper middle-class family. Bank manager Joy Sengupta and his wife Rohini, head teacher at a large school, are liberal, though not actively engaged in politics. Their world is disrupted when they learn their teenage son Bobby, studying Computer Science at a private university in the small town of Manhar, has become a leader of a Hindutva group called the Nationalists. More alarmingly, Bobby may have been involved in the disappearance of a Muslim student, Altaf. The novel deals with Joy and Rohini’s attempt to find out the truth behind Altaf’s disappearance and to extricate Bobby from the thrall of the Nationalists. Bobby’s new perspective is extreme. He says, for instance, that the college history professor is corrupting students, and is, “Making them slaves to foreign ideas… having them believe that all good things have come from Muslim and Christian invaders.” The couple go to Manhar to investigate and the story moves between the alleys and hubs of the town, and the upper-class living rooms of Kolkata.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Kolkata, where Basu grew up, is a common setting in his novels: Kalkatta (2015) explores the city’s underbelly of prostitution and neighbourhood gangs of the ’70s; his previous novel, Sarojini’s Mother (2020), has a woman coming to the city to look for her biological mother. In this book, added to the themes of identity and belonging, is the search for where a country is headed.

Speaking to Open from Kolkata, Basu, 65, says he never starts novels with a theme in mind; instead, he starts with a story. “In an Ideal World came to me organically during the pandemic. It was an exceptional time also because of the phenomenal rise in hatred among us Indians.” While differences in opinion had always existed, there was for the most part a tacit understanding to disagree civilly. That code is now replaced “by a climate of vitriolic hate”. Now, “Disagreements are branded anti-national, inviting the wrath of the authorities. This is not simply a political matter; it’s much more than a clash between rivals, such as the BJP and the Congress.” Basu’s novel does not mention the ‘Congress’, ‘BJP’,

‘Marxist’, ‘Naxalite’, or ‘Communist’, or even current leaders. Instead, the novel’s conflict is the one which he says is “Tearing at the core of our civilisation, centred around the question, what kind of a nation are we? One side of the polarity has us as a secular, pluralistic nation. The other view is that of India as a Hindu Rashtra—a land, primarily, for the Hindus. This division has occupied our political and psychological space, and permeated our families and close relationships.”

This division occurs within the Sengupta family. What made Bobby turn against the liberal positions of his parents and embrace the Nationalists’ cause? Was it simply a late rebellion against his parents? Joy and Rohini believe that they have followed the liberal stance of not brainwashing their child, allowing him to form his own ideas. However, as the novel illustrates, as they didn’t brainwash their son, someone else did. Bobby lacked a defence when exposed to the vitriolic ideology of the Nationalists. Extreme ideologies are historically attractive to the young—both the extreme left and the extreme right can sway them with facile solutions to complicated problems, says Basu. “It was just so with Naxalites in Bengal, who advocated assassination and terror as tools to bring about a revolution. Obviously, that experiment failed miserably.” He had seen this growing up in Bengal in the 1970s. The growth of private universities in regions remote from population centres, says Basu, also has a part to play in shaping youthful political opinions as well. Isolated from the mainstream, many students lack realistic reference points, and the intellectual hardware to argue against political recruiters.

Additionally, the novel implies if students like Bobby are not consistently encouraged to read, they may become more susceptible to extremist views. His father Joy remembers how Bobby “cleared out storybooks bought by his parents over the years from his bookcase, and replaced them with exam preparation guides.” Joy goes to his own study and looks at the shelves.

“Live Free or Die… Gorky’s Mother. Books that had lived through police raids and floods.” Basu points out many students and parents focus on academic excellence purely for material success, “as opposed to appreciating the value of a broad education for enlightenment.”

The book asks why would a child of well-to-do and progressive parents, who has no real grudge against the state or minorities, take to right-wing extremism? Basu’s view is that children of struggling families see more facets of life and can form their own ideas. “But with someone like Bobby, a solitary idea bore fruit easily in his uncultivated mind.”

Joy himself had been a part of his college’s political scene. He was eager for the great Revolution of the Left. Superficially, this is not unlike the author’s own student days when he was a leader in the Students’ Federation of India and an active member of the Communist Party of India, though he subsequently left. Basu, however, stresses that Joy was not modelled in his image. “I’ve known many individuals who in their student days were, loosely, what you would call progressive. They were political activists, and some were involved with theatre, literature, music, etcetera.” But many, like Joy, later moved away from their expressed ideologies.

While Joy is the primary narrator, Rohini is also a force in the story. She is more pragmatic than Joy, and pretends to be sick to lure Bobby back to Kolkata to get the truth about Altaf out of him. It is mostly her drive that pushes the effort to extricate Bobby from his new cause.

One of the strengths of In an Ideal World, is that Bobby is no villain and nor are his parents faultless exemplars. In some ways, Bobby is a device to analyse his parents and their kind, with their comfortable, open-minded lifestyle, their calm assumptions of virtue, who distance themselves from the mess of contemporary politics. Bobby has several redeeming moments. For instance, he empathises with their house help, who helped raise him, and has a seriously ill son. He finds his liberal parents’ cursory concern unacceptable. Such instances are what partly lead him to choose a different path.

Joy recognises his son’s alienation to some extent, but tries to imagine a situation where urban, educated liberals content with discussing politics at parties meet small-town, down-to-earth, rigid conservatives, and asks himself: which then is the real India? The question remains open in the novel.

As Basu warns, such situations of right-wing extremists overrunning universities are not just likely, they are actually happening. “You simply need to attend to social media to find posts from all parts of the country, sometimes from people who are apparently well-educated, spouting rabid hate. News of campus eruptions are all too frequent.”

This novel, well-paced and gripping, with plausible characters, although Bobby is a less believable figure, shown solely to be a prisoner of his ultra-nationalist views. What the book brings out vividly is that extremism is closer to home than we realise.

Uncomfortable realities are a constant in Basu’s works. He experiments with languages as well as different genres. His first four English books are all historical fiction. Although he’s not a professional historian, he’s always loved history and grew up with a rich palate of historical novels in Bengali, like those by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. “It is definitely a possibility that I’ll go back to historical fiction, if such a story appears to me and arrests my mind.”

As a bilingual writer, the language Basu chooses to write in is determined by the imagery of the story that appears to him. “My short story The Japanese Wife (2008) is set in the Sundarbans, so it could have been written in Bengali. But the first line of it appeared in English in my mind: ‘She sent him kites.’ That set me down a particular linguistic path.” His third Bengali novel, Tejaswini O Shabnam (2008), translated as The Endgame, is set in Iraq and involves two Indian women during wartime. Although it’s a global story, the impetus to write it occurred during a visit to a Bengal village where he met young girls who were rescued from trafficking. That starting point prompted the choice of the language.

Inevitably Basu places great importance on translations and feels they are not given enough importance. “My late mother was a prolific author of Bengali fiction. Not a single piece of her work has been translated into English. It is our misfortune that some noteworthy Indian authors haven’t been read beyond their native milieu.” Although translations into English and other Indian languages are now taken much more seriously, he feels there’s still a long way to go.

Basu’s eclecticism is mirrored by his career, as he studied mechanical engineering, then worked in advertising, filmmaking, freelance journalism, teaching, and writing. “Rarely does an author begin life following the solitary ambition of writing and doing nothing else,” he confesses. Although the arts dominated his consciousness from an early age, his professional and vocational choices haven’t necessarily reflected his passion, but demands of circumstances. As he says, “I have taken the scenic route but ended up squarely as an author.”