Kalki Koechlin: Dragon Queen

ONE OF THE biggest lies mothers tell themselves is of the unalloyed joy of having and raising children. Culturally mandated to enjoy the process of giving birth, women need extraordinary courage to break through the silence and speak the truth. Yes, motherhood is not all cupcakes and baby showers. Yes, women don’t tell each other the truth about it. And yes, children are not the be-all and end-all of every woman’s life.

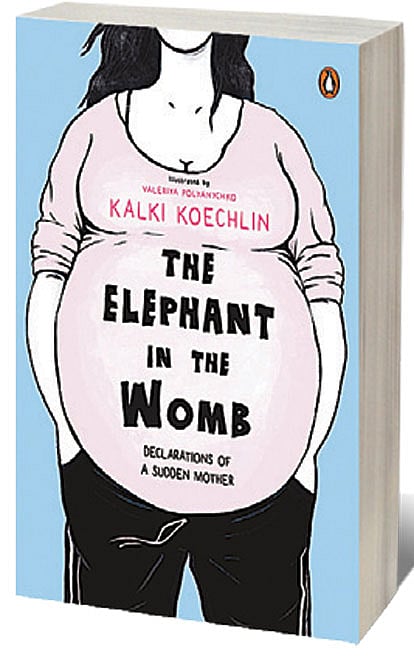

So welcome Kalki Koechlin to the difficult art of truth-telling and thank you for your honesty. The Elephant in the Womb (illustrated by Valeriya Polyanychko; Penguin; 256 pages; ₹ 399) begins with the two abortions Kalki has had, which underlines the choice that women have but rarely exercise. How many mommy memoirs begin with abortions? Or talk about miscarriages? Or about loss of libido? Not many. But then Kalki has never been one to colour within the lines. As the child of French hippies who made India, specifically Tamil Nadu, their home in the 1970s, she first burst onto our screens as the Lolita-like Chanda in former husband Anurag Kashyap’s millennial reimagining of Devdas, Dev.D (2009). Over the years, she has embodied the unexpected: speaking fluent Tamil, looking perfectly chic as a Frenchwoman should and being able to inhabit characters as diverse as a girlfriend whose Hermes handbag is her most identifiable characteristic in Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011) and a disabled, bisexual woman in the stirring Margarita with a Straw (2014).

Ask most women about details of giving birth and they will blank it out. “I wouldn’t have remembered it if I hadn’t journaled it,” says Kalki, 39. As she writes in her book, “Nobody told me to prepare for an alien invasion that would turn my insides out and transform me into a human incubating system of toxic gases and chemical imbalances.” The other aspect of motherhood is the societal structure, says Kalki, which pits women against each other. “We have such few spaces left to talk in, to laugh in or cry in,” she says, “We need to do it, otherwise pregnancy is such a silent, invisible and solitary experience. And you wonder is everyone going through it, or is it just me?” More than that, she says, parenting and motherhood are pitched to us as such rites of passage and the ones who are not doing it are portrayed as outliers that it is difficult to stand out.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

As a result, there is little understanding or appreciation for how it’s done. As Kalki writes, pregnancy is usually portrayed in stereotypes. A pregnant woman is “either the crazy hormonal bitch who needs to park herself on the sofa for nine months and eat a lot of junk, or the magical, maternal, filtered Instagram mum, who is perpetually photographed in soft sunlight falling on her newly found curves.” But in actuality, says Kalki, motherhood means exploring a new part of yourself, giving up what you’re doing, re-evaluating what is important and deciding how you bring up your child, but there is such little education on it.

She’s seated comfortably in the busy lounge of a five-star hotel in Delhi, which she is visiting for a shoot for the second season of the Amazon Prime Video hit Made in Heaven, and though she is away from baby Sappho, all of 18 months, she is relishing it, as she should, the idea of a time-out to meet her brother.

Motherhood is not an easy journey and her book is a testament to that ambivalence about children. It is also a manifesto of the changes we need in our life if we are to create a safer, healthier and happier environment for our children. There are so many questions that a new parent has to deal with—you’re nervous, you’re liberated, it’s all consuming, it requires total dedication, it calls for a total sacrifice of your identity without accolades, but then it’s all about how one can’t depend on one person for everything. “We need the community back,” she says, “And we need corporates to consider that the time spent by their employees with their families is valuable, otherwise you just have the public space encroaching on to the private domain.”

The book, beautifully illustrated by Kalki’s Goa-based friend Valeriya Polyanychko, captures all this in striking illustrations. There is the monster emerging from Dragon Queen Kalki’s womb; the nipple of the breast that won’t pump milk; Kalki as a lonely and sleepless bartender with one regular customer. There are other illustrations that foreground her partner, classical pianist Guy Hershberg, who has written a witty chapter on how his life changed with the arrival of little Sappho—not in the least that Sweet Kalki became Dragon Kalki and, as Kalki remarks mischievously in the accompanying illustrations, never quite changed back to human form.

This is a book that is wise beyond its years, but equally it seeks to bring India up to date with the global wisdom on birthing. It talks of the unreasonably high rate of caesarean births, the advantages of a water birth and the importance of prenatal yoga. It takes the focus away from a family decision (as is most often the case in India) to become the mother’s informed decision. The mother’s mental health is important as is the baby’s well-being—Kalki makes a case for how we need to be empathetic to the growing pains of the child, whether it is when he is teething or whether she is not getting enough milk. “Remember, babies can’t speak,” she says, with her trademark wide smile.

There is great love for Sappho too, and a growing curiosity about her own parents. What was her own mother’s experience when giving birth to her? What made her father hitchhike all the way from France to India in the 1960s? Kalki is a writer and there is one script or two still bubbling inside her. She has learnt to value playtime not merely for Sappho but also for herself—whether she is painting, drawing, writing, she is alone with herself and her thoughts for two hours every day. It allows her to look inside herself, to talk to herself, to be. As she writes in the book: “The act of birthing, of parenting, of life-ing requires at all times a certain flexibility from us, and like an actor who learns their lines over and over again a hundred times before finally performing on a stage, we must know that even if these lines don’t change, their rhythm and intonation changes every night, depending on what your co-actor does, or depending on whether or not you get a laugh at a certain line from the audience. And sometimes even the lines change.” That’s great advice for any occasion.

And she’s not in a panic to get back to work. Having completed one of the films in the Netflix Tamil anthology Paava Kadhaigal (2020), she’s said no to six projects but also accepted those she really wants to do, including a movie shot in London with Deepti Naval called Goldfish. There are also ads, performances, monologues. She is taking a screenwriting course with a friend. And really, she says, how much do you need if you already have an apartment, enough to afford the education of your child and to live comfortably?

With so much judgement flying around about parenting, the question at the beginning of every mother’s journey remains: are we raising little tyrants or wonderful little human beings? Babies take but they give too, writes Kalki, and indeed that is the conundrum at the heart of modern motherhood: women live in lockdown almost their entire lives, struggling for me time, outside time, play time. If mums are happier, so will the children be. But it’s not the work of one couple, one family, or one country. Society as a whole has to understand that raising the next generation is everyone’s responsibility. And every parent, especially every mother, could use the extra help. Not be left alone to stew in a mixture of rage and helplessness.

And yes eventually love. As Kalki writes in The Elephant in the Womb: “I’m ok with love beyond description/ Love that overrides pain and prescriptions/ Love that makes me sing to her at odd hours of the night/ Love that hangs on to the creases between her little fingers/ Love that makes me cry with all my might.” Children may grow up, leave the nest as quickly as they can and never look back except for help, but parents will always be parents—just like Kalki’s mother, worrying about her even at 39, about whether she has taken her vitamins or gone to the loo before a long road trip. Indeed, as Kalki writes, I think I will always have the urge to fly across cities when I hear Sappho crying on the phone.