It’s the Economy, Stupid!

THE YEARS FROM 2009 to 2014 were a sort of calm before the storm in Indian politics and policymaking. The United Progressive Alliance (UPA) had won a second term and the activists who powered that victory wanted a much more expansive social sector agenda than what was possible under the political circumstances. They got what they wished but that led to increasing complications and ultimately political incoherence by 2013. The all-round expenditure boom inevitably led to a series of corruption scandals. The coalition was finally undone by the Narendra Modi storm of 2014. Its constituents are yet to regain ideological coherence.

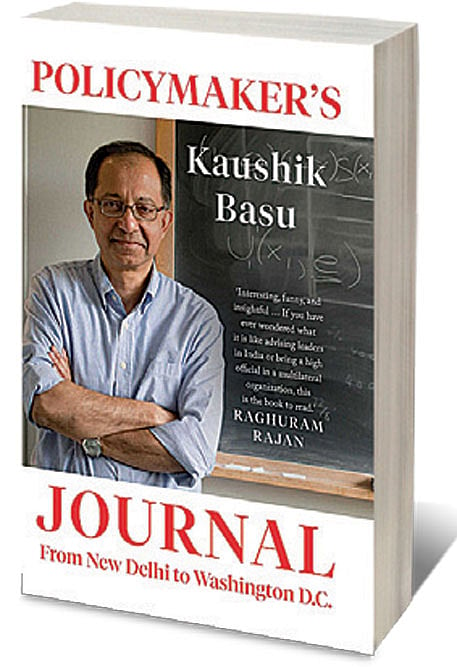

Written as a diary recording the events of his time as Chief Economic Adviser (CEA) (2009-2012) and later career at the World Bank, Kaushik Basu’s Policymaker’s Journal: From New Delhi to Washington DC is meant to convey a different flavour from the earlier companion book An Economist in the Real World: The Art of Policymaking in India (2015). But even the present volume lets in some interesting observations about policymaking in a politically difficult country like India. He notes, “Everybody or a majority has to be in approval for a decision to move. This is best described as a ‘vertical democracy.’ But there can be another kind of democracy. Everybody has a say but not on all decisions…India needs to shift from its relatively vertical structure of permission system which slows down decisions to a more horizontal, partitioned democracy.” The date of that entry is January 13th, 2010. This was relatively early in his tenure as CEA but one cannot help speculate that Basu noted the problems afflicting decision-making in an unwieldy political coalition early on.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In another instance, Basu recounts a meeting on the Food Security Bill, the brainchild of activists in the National Advisory Council. The calm manner in which he reconciles his political sympathies and the economist in him is worth noting: “My problem is my instinctive sympathy with these activists. Most of them are genuinely well-intentioned, and have little interest in money. I like that. I am aware that they often make mistakes. I have had lots of arguments with these activists wanting to enshrine everything as a ‘right.’ I keep reminding them that to enshrine something as a right, when you have no way to ensure that the right can be fulfilled is to diminish the value of a right.”

These debates go to the heart of the policymaking morass of the UPA government. On one side were activists who wanted “rights” for everything and a pristine environment. On the other side was the problem that unless the economy grew at a much higher growth rate, these rights would remain an illusion. Some of these rights required compromises—such as a looser land acquisition regime—that had become a political impossibility. These dead-ends cast a shadow on even relatively simpler matters such as the appropriate fiscal and monetary policy mix in those years. The government wanted higher growth, to fulfil its social sector promises, but the inflationary surge of that time made it clash with the RBI. The “rights” approach and growth came into conflict with each other.

Basu does not explicitly mention these conflicts but lets some nuggets of information slip in. Observers who know something of those years can figure these issues out instantly. Basu the economist is too diligent to disclose anything that may prove embarrassing to his former colleagues but the diary is a useful catalogue of behind-the-scenes events of that time.

Reading the book makes one understand why intellectuals held the UPA in such high esteem and the reverse of that emotion in industrial strength. Sample this: “The more I see the prime minister alongside other politicians, the more I am convinced he stands heads and shoulders above them. Like Nehru, he is truly passionate about India. My conversations with him are almost never about politics and everyday political machination. It is always what we can do to enable India to do better.”

These are heartfelt words from one intellectual about another one. The trouble with intellectual life is that it finds it hard to blend with political life. No one can know that better than the former prime minister and his chief economic adviser. An even bigger spot of trouble is that when intellectuals are elevated to lofty political office in what is a fiercely competitive democracy, there is serious danger that they will be overrun by events.

That is exactly what happened to the Manmohan Singh government. In practice, there was a diarchy of sorts with Sonia Gandhi and the top leadership of the Congress party shouldering political responsibilities while Singh managed the administrative side. But that clearly did not work well. While India recorded stellar economic growth in those years compared to the mediocre record later, power somehow ebbed away from Singh’s coalition government. Basu was prescient in noting the reasons for the malaise. Three months before he demitted office in July, 2012, he gave a speech at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington DC where he noted that decision-making had slowed in the government and pressing reforms had stalled. Back in India, his remarks created instant controversy. The clarification he issued was revealing: “I specifically mentioned that the problem with the GST reform was that the opposition realised this is a good reform. Therefore, it was reluctant to let it happen under the current regime. A single-party majority government would not face this problem. If there is a single-party majority in the next election, that will facilitate such reforms.”

These were prophetic words. The single-party majority government that came to power in 2014 did manage to get GST passed but three years later, and with a poisoned chalice necessary for the required political compromise. The consequences are for everyone to see. His first prediction, that the opposition does not like good reforms to pass is an Iron Law of Indian politics.

In such bare-knuckled and vicious political fights, there is little that intellectuals can do, prime minister or otherwise. The present discontent of the class is therefore a bit mystifying: why hanker for proximity to power when you are, effectively, powerless?

The real charm of Basu’s book lies in sketching a picture of intellectual life in high places in New Delhi in those years. There are lunches and dinners with the aristocracy of learning: Lord Robert Skidelsky (the author of the definitive biography of John Maynard Keynes), Emma Rothschild (another great historian and author of the magisterial Economic Sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet, and the Enlightenment) and a host of other scholars. It is natural that latter day Delhi appears arid and deracinated to the author.

The book is valuable as a ringside appreciation of historical events as well as capturing the charm of its time. There is, however, something to quibble about as well. Basu was a participant in many of the debates and meetings on the interplay between fiscal and monetary policy of those years. As noted earlier, he recorded these events. What is missing from his diary is a candid economic appreciation of these debates. Did the Delhi policymakers have a shape of the Phillips Curve in mind, one that differed from the RBI brass in Mumbai? What was the basis for this differing perception in the growth-inflation trade-off? What were the roots of these differences in the minds of policy makers like the late Pranab Mukherjee (who was finance minister at a crucial time) in contrast to the observed economic record? Sadly, Basu’s diary does not record these matters. As a gifted theoretician he certainly will have something to say on the matter. His readers would like to know.