‘I want to treat facts of history as sacred,’ says Navtej Sarna

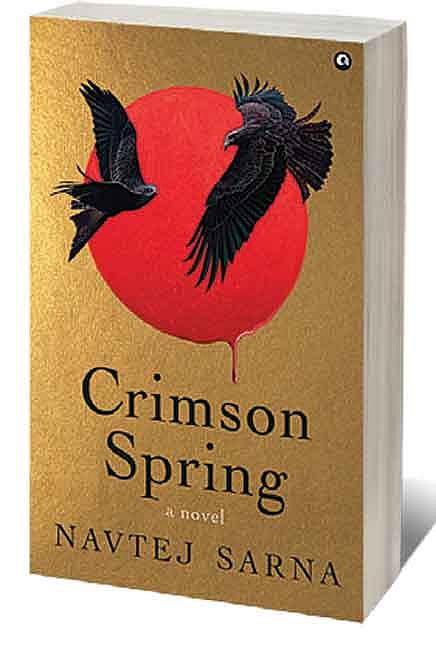

THE JALLIANWALA BAGH massacre that occurred on April 13, 1919 proved to be an inflection point in Indian history. The event has come down to us through textbooks and academic books, archives and retellings. Now, author and diplomat, Navtej Sarna brings alive the massacre in a true fiction novel. Dedicated to “the martyrs of Indian freedom,” Crimson Spring (Aleph; 312 pages; `899) brings the atrocity to life by viewing it through the eyes of nine characters—Indians and Britons. The novel’s prologue opens with the facts; 25,000 people had gathered at Jallianwala Bagh on that Baisakhi day. Sarna concludes the prologue with, “These then, are the facts. Even a hundred years later, the facts speak for themselves. The before and the after is only history.”

In this novel, Sarna uses historical facts to tell the story of people. Crimson Spring is a people’s history, which gives us Punjab of the early 20th century. We see a Punjab simmering with tension after the deportation of Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal, leaders who were spearheading the protests against the Rowlatt Act. We see the walled city of Amritsar with “its twelve gates, its sinuous lanes becoming narrower and narrower as they snaked into its crowded interior”. The city is peopled by characters like Maya Dei who prays at the Golden Temple at dawn and Lance Naik Kirpal Singh who is eager to meet his family after the war. And then there are the more recognisable figures, such as Udham Singh and Michael O’Dwyer. Through the story of characters, Crimson Spring serves as a one-stop guide for the human story of the Rowlatt Act, the Ghadar Movement and the Indian soldiers’ participation in the First World War.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

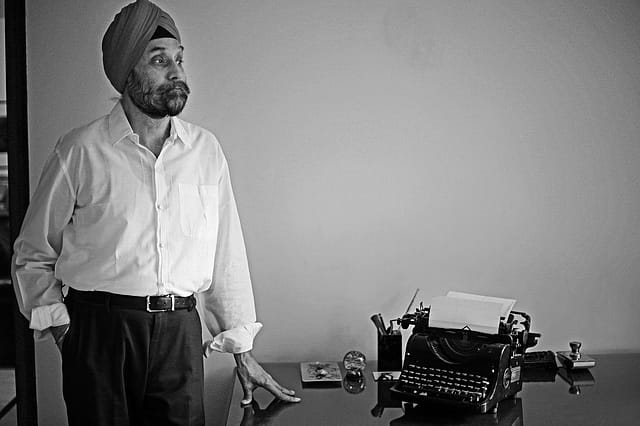

Delhi-based Sarna speaks about his wish to write a Punjab book and how writing and diplomacy fed each other. Excerpts from the interview.

This book is based on facts. But it’s a novel. Could you walk me through that decision of making this a novel?

It grew very organically. It has gone through a long process of thinking and tossing around and filtration. If I now go back to some of the passages I’ve written, some of the books I read, it goes back 10 years. I started thinking of Jallianwala Bagh in terms of a subject to address when the centenary came in sight in 2012, 2013. And in my head, this was one discrete subject, and then I also had long wanted to do an early 20th-century Punjab novel. I wanted to distil some of the ways of life, some of the things that were happening about which I had read, I had heard. Increasingly, I thought that the next generation doesn’t really have something good to read about them, except history books etc. And I wanted to explore that—the Ghadar movement, the Sikh soldiers who fought in the First World War, the reform in terms of Sikh thought, the education aspect, which started in the early 20th century by the Singh Sabha Movement. And, of course, how it all meshed into the freedom struggle. In my head these were two different books. But sometimes you realise that there’s only that much you can do.

Then the second thing is that actually all this fits in. I had neither the time nor the capacity to actually go looking for some completely new piece of archive that nobody had ever seen, which would merit a new nonfiction book. Otherwise, it would be a rehash of so many books that exist and I was convinced that the best way to bring in everything is to do it as a novel. And set it against the Jallianwala Bagh to explore all the other historical parallel trends, the streams of social, cultural, political importance that were happening. So that’s where this idea began, and it slowly kept changing form as it went along.

In the prologue you write, “These, then, are the facts.” As a novelist what is your relationship with facts? How did you strike a balance between fact and imagination?

I’m obsessive about facts. I want to treat facts of history as sacred. I spent a lot of sleepless nights wondering, can I change this or what exactly was that. And then when I was revising my drafts, I said, ‘Where the hell did I get this?’ And then I had to open this whole almirah of notes and I had to keep on digging to know where I got which fact from. Because you know, over six-seven years you gather them from different places, and then you forget where it was. I don’t do footnotes. As far as known facts are concerned, I did not change anything, to the best of my knowledge.

My view is that one has to be very careful with actual historical characters. Like in this case, there’s Colonel Dyer, Michael O’Dwyer and Udham Singh. Now these are actual historical characters. There’s a limit to the liberties you can take with them as a novelist.

I constantly feel that there are people who may only read this one book on this subject. So, I did not want to invent anything about these characters, except when you start giving them an internal life, when you start giving them thought and words and emotions then, somewhere you have to make sure that it’s in the broad direction of reality.

It may not be exact. But for instance, Udham Singh, he talks in the book. It’s like a diary or a monologue, but actually most of it is based on his letters. So, it’s not completely invented. Yes, the language is, the tone is, that’s the character you invent, or you embellish. But the broad trend has to be in the same direction as you think the historical figure would have gone.

That’s why I mentioned it in the author’s note very clearly that I have taken some fictional liberties with his early life on which facts are barely available, some to make it dramatically cohesive, how he links up with the other characters and all that. But again, it’s in the broad trend of his movements. It’s not completely off the moon, so to speak.

And at the same time there’s one issue there which is the basic decision to show whether Udham Singh was in Jallianwala Bagh or not that day. Now a lot of people have taken liberties with that. The movie Sardar Udham shows him there for hours and hours. But I then made a choice based on his own statement. I got this particular quote from his trial transcript, in which he says, ‘I wasn’t there. I was in East Africa.’ In my mind, a person like him, when he sees that he is going to be hanged in any case, would have made a big thing, ‘Yes, I was there. I saw it.’ He had no reason to lie at that stage.

But anyway, to come back to your question, the fictional characters, there are many in this book. You have full freedom how much of fact you want to pin into that. For instance, there’s a protagonist who is a soldier in the First World War. Now, I have invented his entire life, but I did not invent his unit. I did not invent where that unit travelled in which year. Even which ship they went on when they were moved from Europe to Mesopotamia, so I still kept the broad historical guidelines. And then there are some middle characters who are inspired by real life characters. But then there are characters on their own. These are always minor characters in real life. But then in fiction they become major protagonists. It’s a mix of a lot of things, but it’s the weaving together of fact and fiction.

The other two characters who are well fleshed out are Punjab’s Lieutenant Governor Michael O’Dwyer and Colonel Dyer. They both had different ends. Dyer has multiple strokes and dies supposedly plagued by guilt. O’Dwyer was assassinated by Udham Singh. What were some of the challenges of creating them?

These are two historical characters. I had to draw a lot on actual history. They don’t have a lead role in the book, they are seen through witnesses. Dyer is seen through his ADC mostly and O’Dwyer is seen mostly through his chief secretary. A lot of their character had to be reflected through other eyes. Dyer did die a pretty lonely death in his cottage, from some accounts a very tormented death. And O’Dwyer carried on being blasé and grand and defending Dyer until he finally met his nemesis in Udham Singh.

Again, I had to be extra careful that I did not let emotion, or any strong feelings come in the way of a restrained literary portrayal. That is actually what I was striving for, because it doesn’t help the literary merit of any book if the writer gets overtaken by emotion and anger and so that had to be shown through other characters. For instance, Udham Singh talks a lot about them and particularly about O’Dwyer, and the anger of an entire people is channelised through his voice.

This book has a lot about the contribution of the Indian soldiers to the First World War. And there is a poignant quote from a soldier— “this is not war, this is the end of the world”. Do you think the contribution of the Indian soldier to the World War has been forgotten? Also, the book brings out how these soldiers are puzzled that the men they were fighting alongside are now shooting at them.

Which is true. There was a tremendous contribution. Firstly, let’s get to that. People were being recruited left, right and centre, particularly in the Punjab. Michael O’Dwyer wanted to be this great hero who would send the maximum number of men, who would actually send the maximum amount of contributions to the war fund. The province of Punjab was really the breeding ground for all this.

Figures vary, but at least a million combatants went to war abroad and about 60 to 70,000 of them died. And they fought in very difficult circumstances. They fought in unknown landscapes against an unknown enemy, against unknown weaponry. They were just issued a gun. And sent into the winter of Europe. They fought in these trenches, and they fought bravely. There were 11 Victoria Crosses that they won.

A lot of them were confused as to who they were fighting for. Initially, the motivation was the money—`11 a month in a debt ridden, poverty-stricken country. These were usually second sons who didn’t have land, who didn’t have anything.

Then, of course, the news started coming back in the letters about how terrible it was—although the letters were heavily censored. Then the recruitment became almost like transcription. They had gone for the money, they had gone for izzat (respect), they had gone for the glory of war. Mahatma Gandhi was actually very active in recruiting them. He helped the British, to the surprise, to the angst of many of his Indian comrades. And then he also realised what was happening. When they came back, they were faced with the Rowlatt Act. And many of the soldiers then became involved in the protest movement.

I’m afraid that we have not recognised them enough, but fortunately when the centenary came by of the war, there was some amount of focus. But you will still see conflicting opinions. There’s an opinion that this was not our war. These were mercenaries. They went for the money and they didn’t fight for the tricolour, they fought for the Union Jack. My point is—it was Indian blood shed on foreign soil. We have a chance to commemorate that. After 100 years, countries are willing to put up a memorial and recognise them. My belief has been that we need to do more.

What are your own memories of Jallianwala Bagh?

I have visited Jallianwala Bagh a few times and it’s always been a very emotional experience. The last couple of visits have actually been quite disappointing because I found that the portrayal of the tragedy is not coming through. The sanctity of the place, the austerity that is needed in a memorial is somehow getting lost in the touristic shape that it’s being given. People are treating it in parts like a picnic spot. But what it needs is to retain its starkness. If you visit a memorial like Auschwitz in Poland, you just step inside, and you’re hit by tragedy because they’ve kept it in its stark form. What we need to do with Jallianwala Bagh is to perhaps recreate its stark form so that everybody who goes there is reminded of the tragedy. The sound and light shows don’t help.

Since you are a diplomat, I must ask you about this line. ‘It was true – British-Indian society was a swirl through gymkhanas and dances and a race for this appointment or that. Routine work took up most of the time and the rest was spent in nursing rivalries.’ Was that your experience?

(Laughs) It’s unfortunately true of all services. As it is other worlds—the corporate world for instance. People have the same rivalries, etc. People spend a lot of time not pursuing some high ideals. There’s a lot of personal ambition. There’s a lot of swiping at each other. There’s a lot of backstabbing going on. That comes through in the book in the voice of a character who’s different. He believes that bright people come here, but they stop thinking. I must say that it happens even today.

As the author of multiple books, such as Folk Tales of Poland (1991), The Book of Nanak, (2003) etc, how have you managed a writing career and a diplomatic career?

I retired only three years ago. This is my 10th book. I’ve been writing before I joined service. I started writing as a feature writer, as a journalist, as a book reviewer. Then I moved onto short stories. This is my third novel. Each book has taken me to a different part of the craft. I have no illusions. I wasn’t born with the gift of writing a novel at 20 something and making it a success. I had to walk up the ladder learning the nuts and bolts. It’s been a great ride. I wrote during service. Not at the expense of my service, hopefully. I wrote in my own time. The two careers fed each other. As a writer, I found I could be a more effective diplomat in many ways, including the set of people I could meet. The sensitivities that I could share with a different set of people in any country. And as a diplomat, it helped with my writing, because it gave me the chance to go to places I would never have been to otherwise and make use of those places.