‘I am not infallible. It comes with age,’ says Javed Akhtar

JAVED AKHTAR LOOKS at his life objectively as a “very tight screenplay”. He says, “I cannot pick and choose scenes.” And indeed, it is almost cinematic in its narrative. A child is born to Muslim college lecturers, the Communist Manifesto, not a verse from the Quran, is whispered into his ear. He grows up thinking Stalin is his grandfather because of a portrait at home. His mother dies when he is eight, he then lives with his maternal grandparents, listening to the same Awadhi story about two sisters Khera and Bera from his grandmother. He then lives in Aligarh with his aunt, is taken to his stepmother’s family in Bhopal and finally moves to Mumbai to be with his famous poet father, Jan Nisar Akhtar, only to leave his home within five days after differences with his stepmother.

Then begins a long period of struggle, which means often staying hungry for days and sleeping under trees, in studio rooms, and sometimes even the porch of a producer who eventually falls on bad days. He eventually meets a struggling actor for whose film he once ghost-wrote dialogues, and the two go on to collaborate on some of the most iconic movies in Hindi cinema as Salim-Javed.

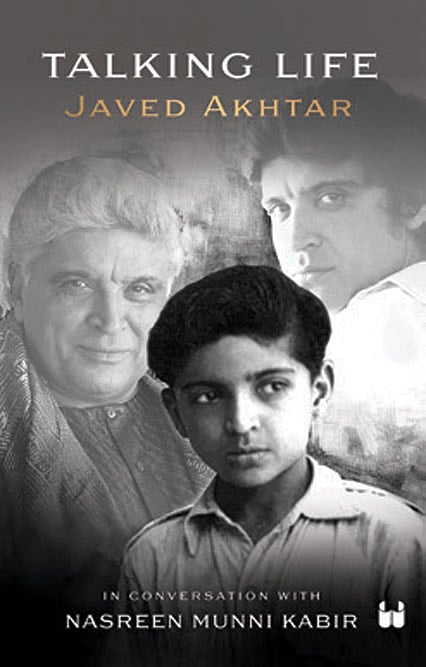

His life could almost be the story of a film written by Salim-Javed. Through a series of insightful questions, film scholar Nasreen Munni Kabir reveals the soul of the man behind one half of the famous moniker in Talking Life (Westland; 224 pages; ₹799), the third in a trilogy that includes Talking Films (1999) and Talking Songs (2002). Here is a man who is unafraid to admit his mistakes, happy to acknowledge his debt to friends, and delighted to enjoy the roller coaster that his life has been—one minute having to choose between a bus ride home and lunch, and another doing the foxtrot with fancy friends in a grand ballroom.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

It is an extraordinary life. As the unofficial poet laureate of India, a position he holds jointly with the other great, Gulzar, he has worked on a slew of movies, songs and verses. At 78, he reveals a series of lessons in the book, which act as a valuable guide. Here are a few of his gems:

Lesson 1: Anger reveals a person’s true self, as masks and inhibitions fall away. It is also highly avoidable.

Lesson 2: A relationship is like a plant and if you uproot it from one pot and replant it in another pot, it will take time to take root. But the plant will grow again because the roots grow naturally. So, have patience.

Lesson 3: How do you create art? Just follow Mirza Ghalib’s advice: practise simplicity, intricacy, forgetfulness and awareness.

Lesson 4: To love life. “To me life is like reading an extremely interesting novel, I want to witness everything that happens in the world. All the major events and future discoveries,” he says.

Lesson 5: Use humour like a shock absorber. It is meant for bad times and comes in handy for making horrid moments tolerable.

Lesson 6: One should not worry about spending, one should worry about earning. People want to make money for money’s sake, I want to make money to buy comforts and luxuries.

Lesson 7: We can’t all be Galileos or Einsteins but at least let us not make the world a worse place than when we entered it.

In a conversation on the book, seated comfortably in friend Naresh Goyal’s house, Akhtar also recalls a time when he thought he was invincible. “Salim (Khan) and I had delivered a series of hits from Yaadon ki Baaraat (1973) to Sholay (1975). These were all first versions. We never needed to do second drafts. Joh likh diya woh likh diya. I remember once saying in an interview around that time, ‘I don’t how people make unsuccessful films.’”

The arrogance of youth has gone now. He adds, “You should be thankful for those who use kind and generous words, but don’t think of it beyond that. Your own objectivity about yourself and your work should remain the same. This kind of praise and admiration should not cloud your own judgement. Listen to people, weigh every opinion and every objection very carefully. It can be wrong but as much as is humanly possible you should look at it as judiciously as objectively, as possible. I am not infallible. I think it comes with age—it happens very gradually when you’ve grown up.”

He is older now, more mature, though the darting eyes and eternal smile remain the same. His mother’s early death remains a wound that is as difficult to heal as his fractious relationship with his father, the poet Jan Nisar Akhtar. He comes from a long line of poets and activists: his great-grandfather Fazl-e Imam was imprisoned in Kaalapani, his grandfather Allama Fazl e Haq Khairabadi was a scholar, philosopher, poet and freedom fighter who participated in the First War of Independence in 1857, and his own father went underground during the freedom movement to evade arrest.

What made Kabir undertake the book on Akhtar? Kabir says: “The first two books were focused on his work life, and as he has a fascinating life and an unusual way of approaching it, I thought it would be good to do a biographical conversation that would record his early years and the experiences he has gone through.” She is passionate about archiving personal histories of Hindi cinema practitioners, so it was unsurprising that she wanted to do this. “Imagine if we had similar books with past people like Mehboob Khan, Guru Dutt, Sahir Ludhianvi, and Majrooh Sultanpuri. How much value they would have in understanding these creative people,” she says.

KABIR’S BOOK COMES at a time when another book has also celebrated Akhtar’s life and times, Jadunama: Javed Akhtar’s Journey (Amaryllis). It has been put together by a friend of over 15 years, Arvind Mandloi, an admirer in Indore, who has interviewed several associates of Akhtar and collected memorabilia around him with painstaking patience. Says Akhtar with his customary wit: “He found photographs that even I had forgotten existed.” With a documentary on Salim-Javed round the corner as well, he thinks the encomiums showered on him have been excessive. “For a few days, I have been hearing so much praise about myself, I’m being mobbed everywhere, long lines of people with books to be signed. But it should not be taken very seriously. I don’t believe in it for a second. The day you start taking your popularity or admiration seriously, you get into problems,” he says.

He is also used to hearing invective about himself on social media in today’s India, being routinely called ‘anti-national’. “I’m called a hypocrite, someone who pretends to be atheist but is actually a jihadi,” he adds. The book chronicles many of his friendships, lost and found. Some are unusual, an early relationship with filmmaker Subhash Ghai borne out of drinking cheap liquor in cheap joints across Mumbai; a long stand-off with singer Jagjit Singh resolved with a sudden rapprochement; a warm bond with musical genius Nusrat Fateh Ali; rediscovered ties with the late Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and the head of his adopted family Mrs Kaul, both of whom had been taught by his father in Gwalior; and his gradual distancing from Salim, with whom he co-wrote 24 films over 11 years, with 20 hits.

Of their parting, he says, “No sudden bitterness came between us, nor did we have a dramatic showdown. I did not say, ‘This belongs to me,’ nor did he say, ‘No this is mine.’ We did not bicker like that. Our parting was most civilised. What made us tick as partners—that connection—had gone but the trust remained.” He lays bare his failings as a husband in his first marriage to actor Honey Irani, which lasted 13 years, and was marked by heavy drinking on his part. “She was inexperienced and strong, and I was mad. That’s a bad combination.” As for his drinking, he says, “There was so much anger, frustration, hurt and bitterness in me, and this came out when I drank.” He is equally candid about his fractured relationship with his father who died in 1976 at the age of 62. “From anger to guilt, from sympathy to resentment, these ghosts don’t leave me,” he says. For Shabana Azmi, his actor wife of 40 years, he has only praise. She broadened his horizons and expanded his world.

And how does he feel about the industry of today after over 50 years in it? He says to me, “Times are changing faster than we are. At the moment filmmakers of Mumbai are slightly bewildered. They don’t know which direction they should take.” As he says to Kabir in the book, “In the 1950s and 1960s, film directors were desi in the way they looked at the world, while today the world vision is wider though the roots are no longer deep.” A rich intellect, a deep sense of ethics, and a way with words that is unparalleled, this is a book to savour.