‘I am a Cyclops’

CYCLOPES TEND TO be asocial beings, choosing caves over communes. Their most iconic feature is the single eye. The male Cyclopes has a two-pronged penis, and the female Cyclopes has three vaginas and one breast. They were originally herders, and their trade with the Two-Eyes—of sheep for spices and tools—allowed them to move from grottos to houses. Legend goes that the Cyclopes are prone to violence, but the fact is that the Two-Eyes meted out violence far more often. Cut to today, and the Cyclopes’ lives are not too different from that of Two-Eyes.

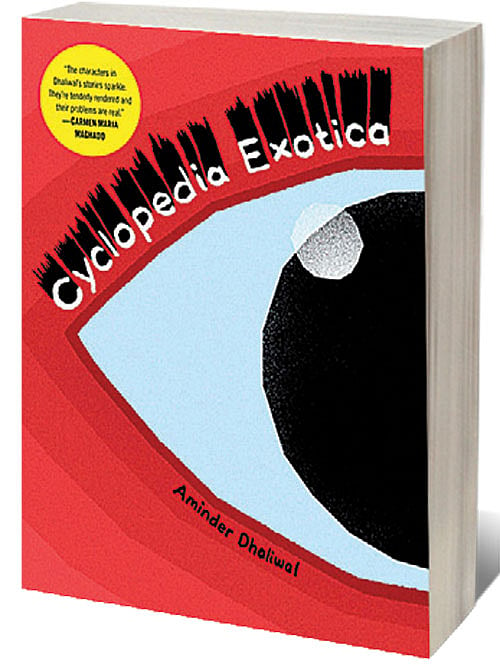

This is the world that Aminder Dhaliwal sculpts in her recent graphic novel Cyclopedia Exotica (Drawn & Quarterly; 268 pages; Rs1809). The 32-year-old Los Angeles-based artist who created Woman World in 2018, succeeds in transforming hot-button issues of the day into comic panels that entertain and enlighten. Her first book was firmly pegged on ideas of feminism, the latest one addresses anyone who has ever felt ‘othered’. Dhaliwal’s pencil is as sharp as her words. With deft strokes, she creates every emotion on the face of her one-eyed Cyclopes; spanning from sorrow to delight; embarrassment to confidence; anxiety to tranquillity. Through the lives of 10 characters—for example Etna a model; a couple, two-eyed Tim and one-eyed Pari; a yoga fiend and aspiring model Latea, and the overweight and underconfident Pol—she examines issues such as race and belonging, identity and representation. Each of the characters has their own demons to fight and battles to win. For example, Etna worries about the repercussions of the choices she made as a model. Pari grapples with whether she should stay home after maternity leave or return to work. Pol wonders if his dream of owning a house and having a family will ever materialise. Cyclopedia Exotica takes the very real problems of our world, especially those around difference and acceptance, and makes stories of them. This is a book that serves its lessons lightly. There is nothing heavy handed to it. It reveals to us that Dhaliwal is a young artist with strong political beliefs and whose heart is in the right place—different and proud.

Speaking over a video call, Dhaliwal emerges as amiable as she is articulate. A self-confessed Potterhead she recently reread a bunch of Roald Dahl books. While she currently lives in LA, she has Indian roots and is of Canadian nationality and spent her early years in the UK. She studied animation at Sheridan College, Ontario. Her day job is a story artist at Sony Pictures Animation. She was named one of the Top Ten Animators to Watch in 2020 by Variety.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In some ways, her day job led to her passion project. She explains that while working in animation, she had to sign numerous Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs), which meant that she could not share the work she was pouring her energies into. In 2016, she was working on a pilot for an animation studio, which got rejected in the final stage. She says, “I felt sad obviously, but I also felt so frustrated that I had lost so much time just making things. You don’t make art to make it for yourself; you make it to be shared. You don’t make it for a vacuum.” The desire to share her art prompted her to start creating art and posting it on Instagram.

She reveals that her decision to draw one-eyed cyclopses emerged from reasons of curiosity and fun. Cyclops embodied that perfect human-but-not-human being. She explains, “There is something I like about the metaphor of the monster. It is a very nice metaphor for race. Instead of having the book be specifically about race, you get to remove that baggage.” While in her previous book she drew numerous women, here she could delve into something more “creepy,” which still had the potential to be humanised and sexualised.

Speaking about her engagement with cyclops, at one point, she blurts out, “I am a cyclops, I guess.” What does that mean, I ask? “It means a lot of your life you’ve felt like you are being stared at or watched. Or just looked at,” she says, adding, “You are seen as something different. Rather than as an entirely realised human. That to me is a cyclops.”

The one eye as opposed to two eyes created its own set of artistic challenges. She quickly realised that a character with only one eye and no nose cannot always emote the same way as a human can. She wanted to create characters with whom her readers could empathise even if at times they might appear “remote” or “cartoony”.

While most books are first created in isolation and then shared on social media with the public, Cyclopedia Exotica has an opposite origin story. Dhaliwal does all her work on Instagram first. She enjoys the process of “instant feedback” where all these followers who know her storytelling can tell her if something is working well or not. She says, “I really like that element of relationship building with an audience. And getting them invested in a storyline before I take it to a book.” A quick scroll through @aminder_d #CyclopediaExotica reveals the passion of her 244K followers. Most of her posts seem to have upward of 50,000 likes and hundreds of comments. The comments range from a simple heart to ‘clenching my heart so cute’ to ‘wait what’ to ‘psst you’re missing an oxford comma in the first panel’.

While social media might help with feedback, the process of taking a story from Instagram and transforming it into a book proves to be labour intensive and is “like going back to zero”. She has to take the single panels and place them near each other to create a sequential storyline. She considers pacing and coherence as she moves from the Insta posts to the single spread comic for the book. She explains, “A lot of it is just feeling it out, and feeling that it is wrong for a very long time, until it starts feeling right again, feeling like how it maybe felt on Instagram. Or it starts feeling like its own kind of thing.” While most of the content appeared first on Instagram, some are special to the book, such as the children’s book Suzy’s One Eye that appears towards the end of Cyclopedia Exotica and is the only coloured section of the book.

Two compelling characters in Cyclopedia Exotica are the female artist duo Jian & Grae who look alike and “explore Cyclopean issues in their art”. They confront questions about vanity and ‘selling out’, the power of two versus the power of the individual. While confessing “all the characters are a little piece of me,” Jian & Grae are especially linked to Dhaliwal. As an artist she finds that she is forced to analyse her own work, for the media and audience, and that carries its own burden. More than that, she also reckons with the fact that as a creative person in Hollywood, she is always made aware of her identity. If she is called in for a job, she asks herself if she is being sought out because of her achievements or because she is a minority as a “woman and a person of colour”. As a person of “Indian heritage,” she is unsettled when people make the assumption that she knows about Hindu mythology. She says, “I am not the person to go to for that. You are just judging that based off of the colour of my skin. It’s a very shocking realisation.”

As an artist who has moved across continents, Dhaliwal knows what it’s like to be an outsider. As an 11-year-old her family moved from Canada to England, and she arrived bristling with a very “thick British accent”. She recounts classmates urging her to say ‘aluminium’ again and again. “It was really odd to me,” she says, “because I had never been an outsider before. And suddenly everyone’s telling you—and they’re telling you nicely, they won’t be mean about it—that you are different. You don’t want to be different. So that was really hard.” More recently, she found that while pitching for a show in the US, the creator of the show stopped her when she was doing a character voice that kept saying ‘Sorry’. He asked if her tone was intentional and why she was doing it. In that moment she realised that Canadians often utter ‘Sorry’ with a longer distinct drawl. She says, “There are little funny moments that add up. And they all add up to you being different when all you’ve ever wanted to be is like a wallflower. Just completely fitting in and no one looking at you. And suddenly you feel so seen. That was all sort of compiled into this book.”

Dhaliwal’s mother hails from Jalandhar, Punjab. Her memories of India boil down to summer holidays and “boring family visits,” where she’d have to visit stranger after stranger and was offered Coke in every house. As a child she remembers throwing up after the fifth house visit because she’d never drunk so much Coke in her life! Her mother ensured that she and her siblings (a sister who is now a physicist and a brother who is a programmer) spoke Punjabi at home. She is familiar with Hindi, thanks to Bollywood movies. But Dhaliwal knows that her argot of Punjabi belongs distinctly to her and her family as it is laden with English words and spoken with a British accent.

This multitude of influences and experiences is the lens through which Cyclopedia Exotica is rendered. It is to Dhaliwal’s credit that this graphic novel provides socio-cultural criticism—on race, xenophobia, beauty and belonging—with an unflinching stare and a slight smile.