How Easy Love Can Be

WHILE EVERYONE I knew was retreating behind shut doors to escape the pandemic, I sought refuge under the monsoon skies of Goa. Except for a few stray dogs, the beaches were deserted, the clouds portentous, the sea a repository of stories that ebbed and flowed into the great Arabian Sea, only to be lost among countless other stories. Someone dear to me died that year for want of oxygen. Many others I knew were silent, out of reach.

I was unaccustomed to the feeling. I’d been photographing people for forty years and travelling was the only constant I knew. So when the lockdown was first announced, I was bereft of ideas as to how I was going to construct my days and nights. Unable to reconcile with talking to the walls or walking in circles inside the house, I coaxed the erstwhile Hotel La Amore at Ashwem beach to open up a sea-facing room for me, which they did, with the caveat that I would have to fend for myself as their staff had gone, the kitchen wasn’t functioning, everything had shut down.

With that room as a base I began walking the beach to stay fit, twenty kilometres a day. The stray dogs followed me, hoping perhaps that I was the harbinger of manna from heaven, for on earth they’d been left with nothing— the tourists had fled, the beaches were no longer a moveable feast of leftovers. It broke my heart to see them so emaciated, eyes large and dead with hunger. In all our own scrambling for food those days, some hoarding more than they needed, those homeless, helpless dogs had been completely forgotten.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

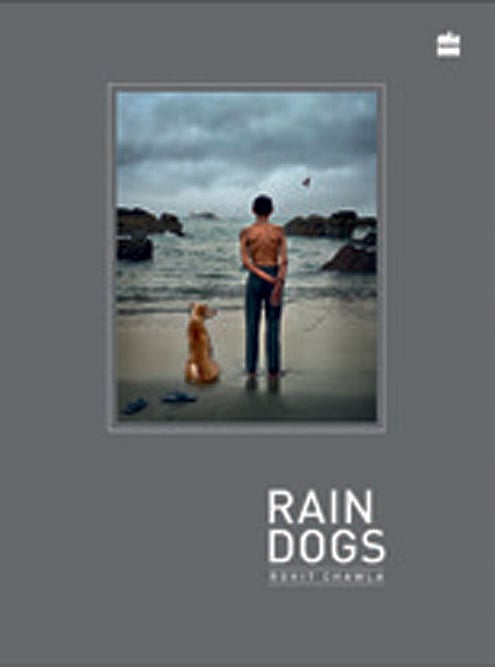

As I recall, when I began shooting these pictures, more than turning a pack of neglected dogs into a photographer’s subject, I was trying to form a frame around my own vulnerability, my disparate thoughts, my inability to articulate those thoughts even to myself. Thus these images are the quietest, most introspective work I’ve ever done. I have always believed that good design is essentially about subtraction and a certain graphic minimalism has been a leitmotif of my craft. The quiet desolation and bleakness of those times against the magnificence of the Goan monsoon became my poetry of choice.

But beyond choosing the time of day, and the quality of light, nothing was ever in my control. Unlike my human subjects I couldn’t coax the dogs to do my bidding, couldn’t predict the moods of the monsoon or the erratic behaviour on my cameras which were overwhelmed by the moisture and became inoperable in days and eventually my trusted iPhone saved the day. But those magical clouds, that endless expanse of water, the shimmering dance of light created a vast ethereal studio where every morning the sea put forth a fresh set of surrealistic props at high tide.

I often wondered whether the dogs were also able to sense that I needed rescuing as much as they did. Someone once said that dogs have a way of finding people who need them. I think it’s true. Though I fed them whenever I was able, the bond that grew between us wasn’t only to do with food. Could they have been aware that, howsoever broken their lives, they were in a strange way restoring mine? As if they knew I needed to remember, and reminded me that love is a simple thing, lost to us at times on account of too much reflection, too much analysis, too much questioning about where our lives are going.

It was three years after I had taken these images that my wife Saloni implored me to look at them again and to my surprise I found that they told a story bigger than I had intended. In some ways it’s a deeply political story as well as a personal one, and I share these images with the thought that the story might resonate with others who, in one way or another, may have been where I was.

(This is an edited excerpt from Rain Dogs by Rohit Chawla)