Hitler Was Not Inevitable

BY DECEMBER 1932, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) was financially nearly bankrupt; it had dropped 34 seats and lost two million votes from its surge in the July 1932 elections. It was doing badly in regional elections too. The movement was unravelling under infighting and intra-party violence. NSDAP was still the largest party in the Reichstag but with President Paul von Hindenburg steadfast in his refusal to appoint Adolf Hitler—whom he despised as the “Bohemian corporal” fit to be appointed at most to postmaster general—chancellor, the game seemed to be over for the National Socialists and their leader. Or so thought observers at home and abroad. The German electorate, evidently, had tired of National Socialist violence and Hitler’s alles oder nichts (all or nothing) strategy of holding out for full power. Yet, a little more than a month later, Hitler was chancellor and the world was set on a course that would make the last century the bloodiest in human history.

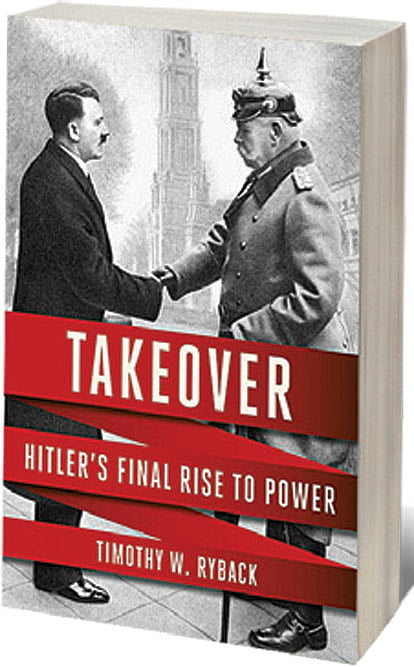

Historian Timothy W Ryback, director of the Institute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation in The Hague and author of Hitler’s Private Library (2008) and Hitler’s First Victims (2014), would have anticipated the question as to the necessity of another book on the rise of Hitler. He answers that unasked query by keeping his narrative limited to the last six months before Hitler became chancellor on January 30, 1933 and focusing on the backroom deals, the making and breaking of functional alliances, the betrayals, the personalities, and above all the details of chance and circumstance without which things might have turned out differently. He has closely followed and compared primary and secondary sources—archival official documents, news reports, opeds, interviews, diaries, cartoons, memos, etc—especially when they contradicted each other on the same facts. Some of the archival evidence had also been rarely accessed before, if at all.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A singular aspect of Hitler’s character was his intransigence, the absolute refusal to compromise. When he budged, it was in rhetorical omissions depending on the audience he was addressing, but never a deviation from National Socialist objectives. There was a lot of dissembling, false assurances, and promises of moderation. None of which, of course, would hold when the time came. Internalising Georges-Jacques Danton’s “l’audace, en core l’audace, toujours l’audace” (audacity, more audacity, and ever more audacity), Hitler gave his own triadic call to arms against the constitutional republic: “I shall continue as I have begun, I shall attack, attack, and attack again.” But by the spring of 1932, as a two-disk recording of his ‘Appeal to the Nation’ evidenced, he had already positioned himself as a political leader rather than a revolutionary.

In August 1932, Hitler believed, led on by General Kurt von Schleicher, Germany’s defence minister and political intriguer-in-chief, that he was about to be appointed chancellor. Hindenburg, by then the final bastion in defence of German democracy and running the country with a presidial cabinet, had replaced Heinrich Brüning as chancellor on Schleicher’s advice but drew the line at Hitler. Hitler’s disastrous meeting with the president on August 13— Hindenburg’s response to Hitler’s demand for full power and single-party rule was a firm “Nein”—was the start of his and NSDAP’s political decline that wouldn’t be stemmed till he had actually become chancellor.

A notable achievement of Ryback lies in sketching the critical roles of pivotal personalities, particularly Hindenburg, Schleicher, Franz von Papen, media baron and leader of the German Nationalists Alfred Hugenberg, Hindenburg’s chief of staff-cum-secretary Otto Meissner, his son Oskar Hindenburg, and, above all, Hitler’s one-time No 2—the man many expected to take over the party once Hitler failed— Gregor Strasser, the forgotten Nazi, more a socialist than a nationalist, a negotiator and pragmatist, a moderate by NSDAP standards. Hindenburg has gone down in textbook history as the senile old president who ultimately made an error of judgment in appointing Hitler chancellor. The fact has always been that if there was one man in Germany in 1932 determined to keep the National Socialist leader out of the chancellery, it was the then-84-year-old president. Hitler consistently underestimated Hindenburg’s aversion to him and believed it was rather his advisors, the Kamarilla, the little chamber of intriguers, who were against him. Meissner, on the other hand, maintained that till his death Hindenburg was in full possession of his mental capabilities, as borne out by the verbatim protocols of presidential meetings.

The Weimar Republic was in a state of Verfassungslähmung or constitutional paralysis wherein Hindenburg had appointed three chancellors in seven months but was determined to adhere to the constitution he had sworn his allegiance to, despite being a staunch monarchist. After the fall of Papen, Weimar Germany’s least popular chancellor whom the president personally held in great esteem, Schleicher was appointed chancellor and was secretly talking to Strasser for the vice chancellorship whereby he could also split the National Socialists. At the same time, diplomatic negotiations were underway with assurances to do away with the most onerous provisions of the Versailles Treaty that would reduce Germany’s reparations burden. With the economy on the rebound and NSDAP hammered in the November 1932 polls, Germany seemed on its way to stability and Hitler seemed a man “with a great future behind him” as Kurt Erich Suckert (Curzio Malaparte) had remarked. But Hindenburg had by then tired of Schleicher’s intrigues and was warming to Papen’s (seeking revenge on Schleicher for engineering his downfall) machinations in search of a new coalition cabinet with Hitler in it. Ironically, Schleicher’s call for a declaration of emergency with the Reichswehr deployed to put down Nazi troublemakers might have saved German democracy, and Europe, but the president wasn’t having any of it.

Ryback’s narrative is replete with accidents and chance. If Papen hadn’t stayed put in the chancellor’s apartment even after his resignation, with the back garden connecting him to the presidential residence, could he have conspired with Oskar Hindenburg without Schleicher’s notice? What if Göring hadn’t managed to ‘kidnap’ Hitler who was on a train from Munich to Berlin and taken him to Weimar where Goebbels was waiting in the critical last weeks? What if Strasser had been found roaming the streets before he left for Italy when Hitler gave in to his advisers’ pleas for a reconciliation with the man who still enjoyed the loyalty of almost half the party rank-and-file? There’s no point wondering about the answers. There was nothing inevitable about much of it but what happened, happened. And events showed that even the shrewdest man in Germany in 1933 could make a mistake. Ernst Hanfstaengl, Hitler’s close confidant and ‘pianist’ who would defect to the US later, thought that Schleicher had miscalculated: “He underestimated Hitler and overestimated Strasser.” And Papen, having finally convinced Hindenburg to appoint Hitler chancellor (ironically to preserve the constitutional republic) told Hugenberg, et al: “In two months, we will have pressed Hitler into a corner so tight that he’ll squeal.”

The day Hindenburg died at 86 on August 2, 1934, Hitler merged the presidency and the chancellorship, “a final act that made good on his promise to dismantle the democratic system, though leaving the Weimar constitution, which he had disparaged so vociferously for thirteen long years, untouched. It remained a testament to the durability but also the fragility of the rule of law, with its Article I serving as a cautionary reminder: ‘The political power emanates from the people.’” That observation from Ryback is the fulcrum of this story which shows how Hitler destroyed democracy through democratic process—as he had promised. History, says the author, never repeats itself, but the events of the past and the present can rhyme. As sharp a warning for today’s Europe and our own times as can be.