Haruki Murakami: Enchanter Emeritus

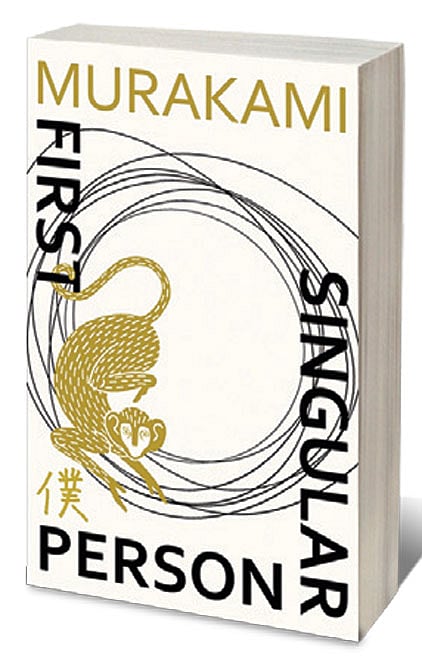

IN THE INTRODUCTION to his short story collection Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman (2006), Haruki Murakami wrote: ‘…everything I write is, more or less, a strange tale.’ And so it has continued to be, as the Kyoto-born writer followed up his best-selling novels A Wild Sheep Chase (1982), The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994) and Kafka on the Shore (2002) with the yet more epic 1Q84 (2009) and Killing Commendatore (2017), to name just a few books on either side of that 2006 publication. First Person Singular (translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel; Vintage; 256 pages; Rs799) is Murakami’s 19th work of fiction to appear in English translation, and he remains a writer of rock star-like fame—readers line up for midnight releases of his books, bookmakers have annual estimates of his odds of winning the Nobel prize for literature. But in these intervening years he has also become a guide to his own work—if not an interpreter of the strange tales he writes, certainly a trusted figure we keep in mind when we read his books.

This feeling of growing familiarity runs strong while reading the eight short stories collected in First Person Singular. They have some of the Murakami markers we now know so well: jazz, the Beatles, baseball. There is a monkey who talks (harking back to the story ‘A Shinagawa Monkey’ in Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman), spilling his confessions over glasses of beer. There are dream-like sequences. Always, there is a moment when the narrator becomes hyper-aware, isolating that moment for its long-lasting relevance in the Murakamian pursuit of the mysteries of the subconscious, of identity, of repressed memory, of forgotten incidents, of what makes the self, of what gives each of us our individual understanding of the world and where we are in it.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

This sense of familiarity may also be brought on by the fact that while the eight tales hint at different life stories, the one time a narrator, in the second last story ‘The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection’, dwells on his own identity, it is ‘Haruki Murakami’, baseball-loving author of A Wild Sheep Chase. It even has a playful aside. The narrator is settling himself in at the stadium, and looking for a vendor selling dark beer. When he spies one and calls him across, the vendor instinctively apologises, ‘I’m sorry, but all I have is dark beer.’ The narrator (‘Haruki Murakami’) reassures the vendor that in fact he was actively seeking dark beer, and then goes on to muse: ‘When I write novels, I often experience the same feeling as that young man. I want to face people in the world and apologize to each and every one. ‘I’m sorry, but all I have is dark beer.’’

LIKE THE ‘Haruki Murakami’ of the story, we readers go to Murakami’s story for Murakamian fiction, and we know too well that when the twists in the tale come and even when they don’t, there will be a surprise. The expectation is that there will be a surprise. There will be a sense of the déjà vu—maybe our own memories will be unlocked, or there will be a reminder of a long-ago emotion, of a fleeting encounter that somehow forms the backdrop to a larger life experience. We can only brace ourselves for it.

I think the familiarity comes not from the fact of a Murakamian trope being repeated once too often—because it hasn’t been, and the stories in First Person Singular are devastatingly moving. They are still unsettling, as Murakami draws readers to a puzzling sensation that there’s something forgotten that lies just a thought or two away, that hyper-awareness about that memory could make our present lives more comprehensible, if not meaningful. These stories collected in First Person Singular, except for the last and title story, however, do not have the foreboding tenor that much of his fiction does. I did not finish this book feeling myself to be half a step out-of-step with the world around me. On the contrary, the collection was something of a consolation, howsoever edgy that consolation may be, especially during this pandemic when Covid restrictions, grief and bruising disruptions have created a seeming dissonance between life as we lived it, and life as it has become and may continue to be for some time yet—between pre- and post-isolation life, between the world we knew and the world as it is becoming. Stray thoughts and memories tend to acquire greater power in this incomprehensible time.

The opening story, ‘Cream’, begins with the narrator saying, ‘So I’m telling a younger friend of mine about a strange incident that took place back when I was eighteen. I don’t recall exactly why I brought it up. It just happened to come up as we were talking. I mean, it was something that happened long ago. Ancient history. On top of which, I was never able to reach any conclusion about it.’ He had received an invitation to a piano recital by a girl he’d barely known at school and had no particular desire to connect up with, but decided to go all the same. He sent off the reply postcard she’d mailed with the invitation, and ‘on a dreary Sunday afternoon in November’, finds himself on way to the recital hall ‘at the top of one of the mountains in Kobe’, carrying a bouquet of red roses on which he had spent all his allowance.

Even before he gets there he has ‘a vague, disconcerting premonition’. ‘Something just wasn’t right,’ he recalls thinking. There are no people about to suggest that a concert is scheduled. And sure enough, the concert hall is desolate. Confused, but with no way of getting any information, he sits on a bench in a park nearby to gather his composure. And then: ‘Once I sat down I realized how tired I was. It was a strange kind of exhaustion, as though I’d been worn out for quite a while but hadn’t noticed it, and only now had it hit me.’ Even in a Murakami short story, you don’t get a louder clue that a ‘strange’ (to use Murakami’s word and to avoid adjectives such as surreal, otherworldly, magical, supernatural) encounter is imminent. And it is, an old man materialises and tells the narrator about a circle with many centres and no circumference.

The narrator’s young friend serves as a proxy for the reader when he remains bewildered about the inconclusiveness of what happened that November day. ‘Things like this happen sometimes in our lives,’ the narrator tells him. ‘Inexplicable, illogical events that nevertheless are deeply disturbing. I guess we need to not think about them, just close our eyes and get through them. As if we were passing under a huge wave.’ And (spoiler alert) about the circle with many centres and no circumference that the old man had asked the narrator to try to picture in his mind, the narrator says he keeps coming back to the exercise whenever something disturbing happens.

‘Sometimes I feel that I can sort of grasp what that circle is, but a deeper understanding eludes me.’

THIS SUSPICION ABOUT there being a larger design behind odd occurrences pervades most of the book. In ‘Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova’, how did an album the narrator made up for a piece in his college literary journal turn up fifteen years later in a small used-record store in New York, and then disappear? And later, how to describe the music when Charlie Parker appears in a dream to perform a track from that album?

In ‘With the Beatles’, why has a young woman called her boyfriend over to her house, but is not there when he arrives? Her brother keeps him company as he waits and insists he read aloud the story he’s leafing through, Rynosuke Akutagawa’s Spinning Gears. They discuss how Akutagawa wrote it just before he died by overdose, at the age of 35. Years later, when the narrator gets an unsettling update on the siblings, he also recalls another girl he once saw in school, hurrying down a hallway, holding a Beatles album close to her chest. What is the connection? He only saw her that once, and yet, he recalls: ‘My heart started to pound, I gasped for breath, and it was as if all sound had ceased, as if I’d sunk to the bottom of a pool. All I could hear was a bell ringing faintly, deep in my ears. As if someone were desperately trying to send me a vital message. All this took only ten or fifteen seconds. It was over before I knew it, and the critical message contained there, like the core of all dreams, disappeared. Just like most important things do that happen in life.’ Why is that memory so sharp all these years later?

In ‘First Person Singular’, why does the narrator have ‘this edgy feeling that, ethically, something [is] amiss’ when he puts on an expensive suit he rarely wears, and steps out for a drink on a pleasant spring evening? He’s having a vodka gimlet and reading his book when a woman seated ‘two empty stools away’ begins talking to him in an accusatory tone. He wonders if they are acquainted. ‘I’m a friend of a friend of yours,’ she says. ‘This close friend of yours—this person who used to be your close friend, I should say—is quite upset with you, and I am just as upset with you as she is. You must know what I’m talking about. Think about it. About what happened three years ago, at the shore. About what a horrible, awful thing you did. You should be ashamed of yourself.’ He pays up, leaves, without challenging her accusation. What is he afraid of?

It is not that the stories are burdened by familiarity—they are not. But over the past couple of decades, we have gotten to know Murakami the writer better. He has explained his craft, in introductions and interviews. He has dwelt on the discipline that he brings to his writing routine (his physical fitness, for instance, that enables it and which is beautifully conveyed in his memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, 2007). He has ‘gracefully acceded to his role as elder spokesman for modern Japanese literature’, as Jay Rubin put it in the Editorial Note to The Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories (2018). As Murakami’s ‘strange tales’ progress, we now know well that we are in the care of too brilliant and thoughtful a writer for the writing to let us down, at least in the shorter stories.