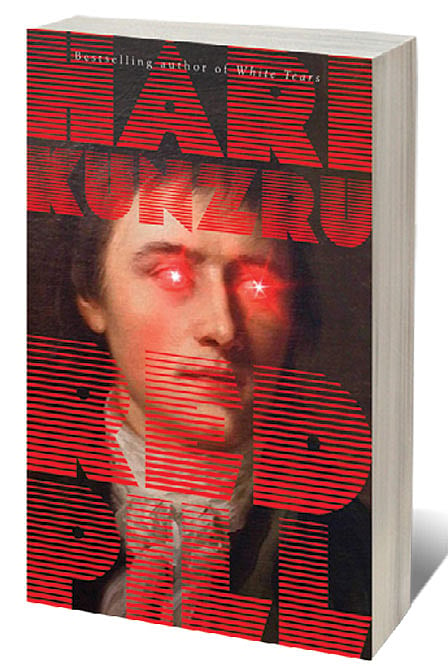

Hari Kunzru: ‘Every one of my dark fears has come true’

‘WHAT IF THE endless reasonable reaction is endless horrified screaming?’ The unnamed protagonist of Hari Kunzru’s Red Pill asks this question towards the end of the novel. He believes that doctors are fundamentally ‘servants of the status quo’. ‘Their work was predicated on the assumption that the world is bearable, and anyone who wants it otherwise should be coaxed or medicated into acceptance.’ ‘But what if it isn’t?’ he wonders. Reading Kunzru’s Red Pill (Scribner; 284 pages; Rs 599) against the current news cycle, one can’t help but align with the protagonist’s sentiment. Does a reasonable reaction to today’s events render us all into the mummy-like figure of Edvard Munch’s The Scream? Haven’t we all had moments in the recent past where we’ve wanted to clutch our cheeks and shriek? And are those who find events bearable complicit?

With White Tears (2017) Kunzru had flexed his muscle as a writer who could turn weighty topics—like cultural appropriation and the Blues, music and musicians—into a thriller. Red Pill elevates his skill to mastery. I read the novel in two sittings, unwilling and incapable of putting it down. The writer protagonist is a whiney grouch, all sulks and no smiles. He leaves Brooklyn for a three-month residency at the Deuter Centre in Germany. Initially one can identify with his dread for social engagements and communal workspaces, but slowly his dread morphs into mania. He is sucked into watching Blue Lives a show where a cop uses a drill on a man’s mouth. A chance encounter with Anton, the creator of the show, takes the protagonist into a maze, where he will forsake not just his family, but also reality. The paranoid mindset, as Kunzru says, “is about perceiving an hidden order of the world that is just out of reach. There is a danger that you haven’t quite understood. In a technologically enhanced world, the problem is that there is basically too much information to comprehend for any one person. One is very aware that things are bubbling up. It is very hard to discern what is real and what is not. There is a threatening atmosphere”.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Threat is that niggling fear we all know; it could be the suspicion that our WhatsApp chats are not secure or our doubt about whether our leaders are telling us tales. Phrases like ‘prescient’ and ‘novel of our times’ are thrown about like pigeon feed into the winds. But Red Pill is all that and more, because at the end of the day, it is a well told yarn about realities that we all are aware of, even if we seldom acknowledge. The politics of the novel—our lack of privacy, our illusions of agency, possible descents into paranoia, the thread connecting the Nazis to the Stasi to the alt-right—never overwhelms the fictional tale. The title of the book is borrowed from the Matrix scene, where taking a red pill reveals an unpleasant truth, whereas a blue pill allows one to remain oblivious. Kunzru’s approach is more explorer than activist, he travels and returns with ugly truths to share with us. Curiosity drives his storytelling; have we forgotten the horrors of the past; how do humans enact horrid deeds on other humans; how do strongmen win elections; how different will our children’s lives be from our parents’; what is surveillance doing to our psyche?

Red Pill ends with the 2016 November election night when Donald Trump is voted into power. Speaking to Kunzru, a Briton who is now based in New York, I ask him his thoughts as the US heads into another election. He says, “There’s this element of ‘I told you so.’ More or less every one of my dark fears has come true. I thought from the beginning Trump was a fundamentally anti-democratic force. Other people would latch onto him who had extreme agendas around remaking America as a sort of Whites-first country. And all that has definitely come true.”

A growing intolerance is a vein he identifies in India too. Measuring his words carefully because of the trolling and threats he’s been subject to in the past by Indian right-wingers on social media, he says, “Narendra Modi’s vision of India is not a plural vision. The death of that idea will be a terrible thing for India and will make India weaker.” If Trump and Modi are similar in the kind of coteries they surround themselves with, and their monolithic worldviews, the Congress and Hillary Clinton share similarities too. Kunzru adds, “People rejected them because they didn’t like the idea of a leader being anointed. And a leader who didn’t seem to provide any new solutions or new alternatives.”

To better understand the fear of the ‘other’, Kunzru lurked on right-wing Reddit forums. While he naturally found these places “depressing” and “unpleasant”, he did identify a certain “intellectual culture”. He studied their arguments to see how his own beliefs and views would stack up against theirs. He says, “I consider it as sort of stress testing; if my views on things are correct then I ought to be able to defend them against the strongest opposing arguments.”

The style of arguments on these forums also intrigued him with their extensive use of irony and humour “especially as a way of disguising extreme positions”. He also found that 1920s Germany used a similar ploy, where newspaper articles would feign levity and claim there is ‘no agenda against the Jews’.

Kunzru delved into this world that he doesn’t agree with because he feels listening is essential. He says, “In the US, UK, India, everywhere, we have to listen to what’s actually being said.”

Aren’t ‘liberals’ often guilty of not listening, I ask. Don’t liberals refuse to engage with ‘opponents’, whether it is at festivals or in print. This is clearly a sticky point that Kunzru has negotiated in the recent past. He was one of the authors who “strongly opposed” the inclusion of right-wing thinker Steve Bannon to the New Yorker festival. At a time when nuance is lost at the cost of brevity, he makes the finer argument that he’d have no problem reading something written by Steve Bannon. He says, “The difference to me is the New Yorker festival is a sort of prestigious gathering that confers legitimacy on the person who is invited to it. It is like giving him an award essentially. I’d have no problem debating with him in print.” He adds, “It’s the same problem with history debates in India. If you force a professional historian who has spent their whole career looking at Mohenjo-daro or whatever to debate with somebody who has an ideological position, you are saying, ‘Well, these two views have equal weight.’ And it’s essentially a free gift to the ideologue. I’m in favour of open debate. I am not in favour of giving people legitimacy, unless they’ve earned that.”

When ideology determines fact, when people believe tales that perpetuate their own beliefs, where does fiction fall, I wonder aloud. Kunzru asserts that the importance of fiction is only heightened. He says, “Fiction is a very good form to understand complex things. You can paint a portrait of an individual in a complex situation. And you can understand how it feels to be in a particular position.”

WHILE KUNZRU WISHES to “double underline” the fact that he is not the writer-narrator in the novel, they do share similar politics. “He is like a version of me that I’d raise an eyebrow at,” he says with a laugh. An interesting narrative arc tells the story of the cleaner Monika, who the narrator meets at the writing centre. The entire section ‘Undermining’ details her days as a rocker in East Germany. She is the quintessential outsider, anchorless and alone, who befriends a punk group and finally feels she belongs. But she comes to know betrayal intimately. There are many twists to her tale, which are best read in the book and not revealed in an article. This section hooks the reader as it reveals the brutalities of the state, especially upon the body and mind of a woman. It also evacuates the reader from the interiors of the narrator’s head. One of Monika’s laments is that it’s ‘shitty’ to live ‘in a country where everything was run by old men. A whole country, reeking of piss and schnapps and cabbage soup’.

I ask Kunzru, what are the dangers when countries are run by old men? He says in Monika’s case, she’s referring to the “sclerotic Communist Party establishment of East Germany”, but he recently learnt that American politicians are getting older and older relative to the general population. The older generation benefit from their experience, but are limited by imagination. He says, “They don’t understand why things should change.”

The narrator in the novel isn’t an old man, but he is a middle-age man who is aware that his horizons are decreasing and his limitations growing; ‘I was getting older, weaker. Eventually I would fall behind, find myself separated from the pack.’

If the narrator is aware of his deficiencies, Kunzru also identifies the growing gulf between the young and the old. He says, “There’s the advancing disconnection between the government of very rich old people and the population which is younger and more insecure. The young and poor people will turn to some other solution, and it will be a more radical solution.”

Kunzru’s novel is deeply embedded in the machinations of the twenty-first century, but it is also an ode to the arts. The narrator might be a self-absorbed writer, but the novel also reveals the realities of writing; the sacrifices that need to be made and the labour that it entails. Red Pill hinged on writing, will be the middle book of a loose trilogy; White Tears dealt with music, and his next novel Blue Ruin will be about the visual arts. The arts have always been the filter through which he has understood the world. Kunzru says, “One of the interesting things about being a novelist is that you’re not a specialist in anything. In a funny way, you have no authority at all. I want to explore all sorts of areas. And talk about them. And I have no such academic standing, no political party. The best thing I have is perhaps a reputation for calling it as I see. All you could do is describe the world as it seems to you and you try to do it as honestly as you can, and fully understanding that’s your point of view. And that will be horrific and absurd to some people. I think there’s a value in that. I don’t think art is going to save us in any way.”