Grassroot Warriors

The stories of the Bishnoi—a community, caste, and religion that mostly resides in and around Jodhpur in the northwestern state of Rajasthan, India—have been recounted time and again. They are celebrated for their environmentalism, their legal battle against Bollywood actor Salman Khan for hunting animals in their region, and their steadfast commitment to living in harmony with nature. The Bishnoi follow a unique way of life, guided by principles that emphasise simplicity, austerity, peace, and sustainability.

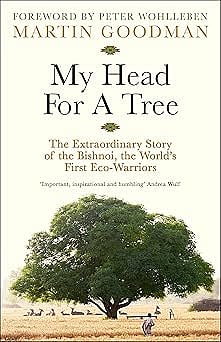

Martin Goodman’s recent book, My Head for a Tree: The Extraordinary Story of the Bishnoi, the World’s First Eco-Warriors, offers an unparalleled and comprehensive account of this remarkable community. Goodman goes into the Bishnoi’s history, society, religion, individual life stories, community initiatives, and contemporary challenges, and vividly explores their collective efforts, organisational endeavours, and the pathways they are charting for the future. From an environmental perspective, Goodman brings to life the intricate relationships between humans and animals, trees and water, deserts and landscapes, as well as men and women, old and young. His narrative is both lucid and intimate, making this one of the most compelling and insightful explorations of the Bishnoi to date.

Goodman’s work reminded me of recent pathbreaking environmental scholarship in India, particularly the writings of Shekhar Pathak and Chandi Prasad Bhatt on the Chipko Movement, where these authors have revisited well-known stories with deep engagement and academic rigor, uncovering new facts and insights, making it both an intensely personal and scholarly contribution. In fact, the book begins with the story of ‘Amrita Devi and the 363 Martyrs.’ In 1730, Amrita Devi, a Bishnoi woman from the village of Khejarli in the Thar Desert, sacrificed her life to protect trees from being cut down on the orders of the king. Following her lead, altogether 363 villagers gave their lives to save the trees. This historic act of environmental resistance is considered a precursor to the Chipko Movement, which later became a symbol of modern environmentalism. The book also takes us to a chapter ‘Passing Amrita Devi’s Baton,’ where we learn about Gaura Devi, Vimala, Sunderlal Bahuguna, and Chandi Prasad Bhatt, who famously stopped tree felling by forest departments and contractors by hugging trees in villages of Garhwal.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

The book has a clear purpose: to present everyday Bishnoi life, society, culture, and religion in the context of nature and the environment, inspiring hope, courage, and commitment in today’s world of climate and ecological crises. This goal drives the author to explore diverse themes, people, animals, trees, events, and organisations. The book is organised into 18 chapters and includes an important appendix featuring the ‘Twenty-Nine Rules’ propounded by Guru Jambhoji, which underpin Bishnoi environmental sensibility and grassroots activism.

Grounded in environmental history, the narrative is not structured in a linear, chronological manner. Instead, it moves fluidly across different time zones, weaving together the past and present in a compelling way. One chapter recounts ‘The Birth of Guru Jambhoji,’ while another, titled ‘The Guru at the Wedding,’ delves into later incarnations of the Guru in his pursuit of nature dharma. The book also highlights contemporary Bishnoi figures, such as a young man who sacrificed his life to protect a chinkara, and another individual dedicated to transforming the desert landscape by planting hundreds of thousands of trees. These accounts provide deep insights into indigenous forestry and the Bishnoi commitment to ecological stewardship.

It is encouraging that Goodman places substantial focus on the contemporary bright spots—people, struggles, and initiatives of the Bishnoi—centred around their religiosity concerning trees and animals. This approach allows us to draw hope not from a proclaimed glorious past but from the present, which is very much alive in our times. The book explores the workings of the ‘Bishnoi Tiger Force,’ strategies for ‘how to live in a megadrought,’ where the kankeri tree is revered as a temple, and the efforts of a young Bishnoi woman in the city fiercely advocating for animal welfare. It also introduces a spirited team of ‘enforcers’ committed to ecological protection. Through these accounts, the history of the Bishnoi comes alive, conveyed through the narratives of people and beautifully crafted by the author. In this sense, the book serves as a fine example of environmental communication. Moreover, its production is enhanced by striking photographs of the region, its people, animals, and trees, making it both accessible and visually engaging for readers.

The book is undoubtedly a treasure for those who care deeply about trees, animals, and the broader environment. The foreword by Peter Wohlleben is particularly fitting in this context. Written in close collaboration with the Bishnoi community, it serves as a further recognition of their contributions, with the preface by Ram Niwas Bishnoi Budhnagar being appropriately placed. This book can also be a valuable companion for those seeking creative resources in community, religion, and people during these times of environmental destruction and despair.