Fantastical Futures

A PARTICULAR KIND of miniature painting that once enjoyed great vogue was the pashu kunjar, or a kind of composite featuring the shape of an elephant but made up of a myriad multitude of animals or humans; for instance, the trunk could be a curled-up cheetah and brow a sleeping antelope. This conglomeration, fantastic in the extreme, was yet always depicted in robust movement.

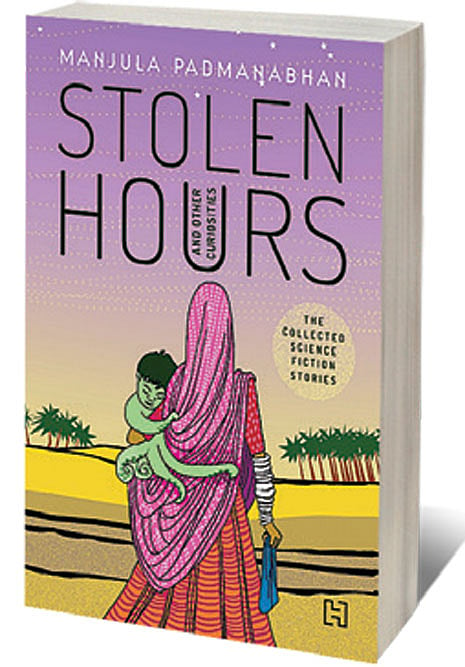

Such a composite could describe a science-fiction anthology; one such as Stolen Hours and Other Curiosities by Manjula Padmanabhan. Billed as “the collected science-fiction stories” it captures nearly four decades of the award-winning, playwright/ cartoonist/ novelist’s work, from 1984 with the most recent one dating to this summer.

Despite nearly four decades, it is a slim volume, with its 25 stories rarely exceeding a dozen pages each. This is an outcome of Padmanabhan’s style, where an idea flashes, and then a whole world is built around that conceit, with a few deft strokes, echoing the Nabokovian dictum that “The writer needs the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist”.

Padmanabhan, like an expert hunter, usually sites her machan in the near future, introduces a technological change much in the manner of the tethered goat, and then observes the unexpected ramifications mosey in, and then takes the shot. Usually, it’s a clean kill. For instance, in ‘India 2099’, written in the now distant year of 1999 to imagine our country a hundred years hence, we learn over the course of a few pages that NRIs have been replaced by ETIs (Extra-terrestrial Indians), that the country is divided into Hindus, Muslims and OMs (Other Minorities), and that the country embarked on a gigantic space colonisation programme in the 2030s, resulting in Mars being renamed as Kalki. In trademark style, the narration also casually mentions that “with limited resources for farming, socially accepted forms of cannibalism were practised”.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In ‘Cull’ written in 2009, India, or at least Delhi seems to have done better, for it is now rebranded as ‘Dilli Continuum,’ which is the capital of Greater India, that stretches across South Asia. Rajpath, has been “replaced by a long-straight block of buildings” and that “nothing remained of the old, white-walled bungalows of the past” and “all historical monuments, including ancient forts and tombs, had been dismantled and rebuilt in vast underground museums”. A future that might yet come to pass.

Padmanabhan combines her ideas with memorable images—a cloned catlike policewoman, a billionaire’s palace floating in low-earth orbit, a mutant who wrecks an arranged marriage, the essence of Mahatma Gandhi distilled as perfume. Sometimes she deploys the scalpel, and sometimes the sledgehammer. Taut observations are told through the measured violence of her sentences. The pain of a miscarriage is described as “huge and brassy, a great boom of raw life energy, pounding its way out, towards death”, while elsewhere “the groom’s house resembled a collision between an oil tanker and a Spanish villa,” and in another story an archaeologist becomes “accustomed to nestling deep in the brown clay bosom of the earth, scratching at the roots of history”.

Padmanabhan also has a marked fascination for biological warfare, toxins, mind control, anthropophagy; for insidious, invisible enemies that strike without warning. The titular story featuring a mashup between acupuncture and the “time function in human beings” evokes Cronenbergian body horror with a side helping of teenage angst.

Padmanabhan, the daughter of a diplomat grew up in countries such as Sweden and Thailand and only returned to India as a teenager, without any knowledge of Hindi or any other Indian language. In the authors’ note, she explains her turn to SF as a natural outgrowth because she had “become a naturalised outsider, a foreigner to everywhere” and that “writing SF is a way of celebrating the ‘other-ing’ that I experience as a young person”.

This thread of an outsider looking in, a nomadic imagination on a permanent exile, runs through all the stories.