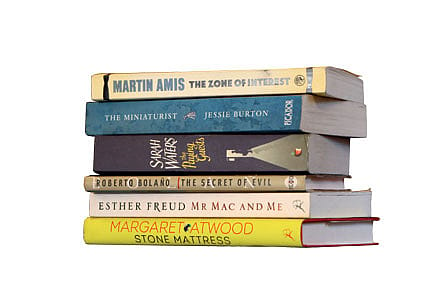

Fall Fiction

The return of a Latin American literary idol, a Holocaust morality tale, pre-WWI England, stories from the shadowlands, a Victorian saga of closeted lesbians and a gay parallel narrative in seventeenth-century Amsterdam

SARAH WATERS is back with a compelling if uneven tale of 1920s repression, in her sixth novel, THE PAYING GUESTS (Virago, 566 pages). Frances, her stubborn heroine of fading post-war south London, is a marvel of British gumption, rolling up her sleeves to keep the venerable family home intact—even making time for a quick spot of self-pleasuring, between the chores. The entry of two working class paying guests, Len and Lily Barber, taken in to help sustain Frances and her mother, will change everything. The household shares its most intimate spaces, and Frances begins to dream of real love, as she didn't with an old flame. Her affair with the almost unwittingly seductive Lily—precious yet clearly appealing—almost survives the obstacle of her husband. But as events take a terrible turn, Waters asks many questions, chief among them the real nature of love; are the two bound only because they have colluded in an awful secret: '[W]as that all, she thought bleakly, that love ever was? Something that saved one from loneliness? A sort of insurance policy against not counting?' Waters' deft touch—most rewarding in The Little Stranger—is missing in the more lurid action. So, the details triumph, more than the big idea. Yet even a bath, overheard, is rich with potential in her able hands: 'There came the splash of water and the rub of heels as Mrs Barber stepped into the tub. After that there was a silence, broken only by the occasional echoey plink of drips from the tap'. The suggestibility of these characters echoes in those still yet restive drops. Brilliant in her examination of class and the smoky trails of earlier eras, Waters is, as always, a reader's writer in this subversive sendup of both domestic and Gothic novels.

ROBERTO BOLAÑO's posthumous collection of stories, THE SECRET OF EVIL (Picador, 164 pages)—just out in the UK and India—has been exciting for fans. These 19 stories range from the typically elliptical return of Arturo Belano (Bolaño's alter ego) in 'The Old Man of the Mountain' and 'The Days of Chaos', to 'Scholars of Sodom', a hilarious two- part account of a visiting VS Naipaul, who worries over the prevalence of sodomy in 70s Argentina. This last tale, a strange bird even for this writer, ends, predictably, in a pronouncement about literary Argentina: 'But, for better or for worse, Argentina is what it is and has the origins it has, which is to say, of this you may be sure, that it comes from everywhere but Paris.' Alternately short and feverish ('Sevilla Kills Me') and self-indulgent ('The Colonel's Son', a zombie saga), these are pale echoes of the weird but trippy The Savage Detectives and 2666—but echoes nonetheless. The Chilean superstar might not have wanted it like this, but read this one as a companion volume; a corollary of the master work.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

There are those who love the latest offering of maverick novelist MARTIN AMIS, and those who cannot stand it. Interestingly adventurous at this point in his career, Amis' 14th novel, THE ZONE OF INTEREST (Jonathan Cape, 320 pages) is a challenge to finish. Set against the Nazi haze of 1942, the story is told by Golo, a promiscuous officer of the Reich who lusts after the commandant's wife, among many others. The full 'meteorology of first sight' unfurls when he falls for Mrs Hannah Doll, and some of the novel's most ripe passages stem from the pairing of these characters, rather than the exchanges between the evil men of Kat Zet I, the eponymous 'zone'. Though the treatment of evil and prejudice is acute, almost hypnotic in its steely perversion: 'With its disgusting and hysterical emphasis on the carnal predations of the Jewish male, Der Sturmer, I believe, has done serious anti-Semitism a great deal of harm. The people need to see charts, diagrams, statistics, the scientific evidence—and not a full- page cartoon of Shylock.' Amis pursues his usual obsession with 'the new unpleasantness' (as his predominant theme was famously termed) in this book, the anti-hero. Yet, the evil is cloying. Perhaps novels about Nazis have to face an unusually high bar, but this one flails nevertheless.

It is difficult to admire MARGARET ATWOOD, that 'quiet Mata Hari' (Michael Ondaatje), that formidable yet playful queen of contemporary literature, and not like her new collection of stories, STONE MATTRESS (Bloomsbury, 280 pages). These nine fables are as wonderfully dark as those she gave us in masterpieces like Alias Grace, with hints of the fiery charm of The Edible Woman (1969). Yet, the spark goes out in places, forty books into her career. In 'Alphinland', the widowed fantasy writer who is haunted by her late husband feels too trite a playing field; in 'Dark Lady', there is overkill in the account of morbid Jorrie, who reads the obituaries religiously in a veritable 'tapdance on the graves'. Likewise 'The Freeze-Dried Groom' and 'The Dead Hand Loves You'—all those fantastic Atwood-ian titles!— beg to be loved but mostly leave you cold. Would-be vampires, a billion-year- old stromatalite, imaginary people: lots to enjoy for those who are not faint of heart, but not so much for the literary reader.

Gothic thrills are promised in the closeted and newly affluent 17th century Dutch world of THE MINIATURIST (Picador, 448 pages), yet never fully delivered. When eighteen-year-old Petronella van Oortman travels to her new bridal home, a grand house in the plushest neighbourhood in Amsterdam, she is greeted by Marin Brandt, her moody sister-in-law, and a sense that all is not well despite their riches. Johannes, her mysterious husband, gives her a wedding present, a cabinet-sized replica of her home that becomes her new obsession, as a miniaturist begins to fill the house with tiny imitations of her reality. Nella longs both innocently and morbidly for the 'hot rod of pain' that is to accompany her wedding night, but her curiosity is perpetually postponed, for Johannes seems to have other desires, which will soon endanger them all. Where does Otto, the Brandts' servant from Surinam, fit into all this, and will the miniaturist ever show Nella her true designs, or help her with her prophecies? As magical as the ride is, there are too many missing answers and a sagging plot results. Written with the rich period detail of the time, an era of forbidden fruit run by burgomasters, JESSIE BURTON's first novel is an enjoyable historical read, as slight as it ultimately remains.

'No one thinks the herring girls will come this year, but there's nothing the fisherman can do without them, someone has to gut the silver darlings, as they call them, and soon the girls are flooding off the train, in a long crocodile behind their pastor, and making their way into the already overcrowded town.' MR MAC AND ME (Bloomsbury, 304 pages) has the implacable rhythm of novels set in the cosy, prelapsarian world of pre- World War I England. Its protagonist Thomas Maggs is the crippled son of a publican, his life full of fishing, farming and daytrippers who visit the Suffolk coast during the summer. His new friend, eccentric Scottish architect Charles Rennie Macintosh—or Mr Mac—sees him through the new order, as soldiers travel through en route to Belgium. When he comes under scrutiny, things begin to unravel. Lacking the drama of ESTHER FREUD'S early novels (Hideous Kinky), the book is still a nice quiet read.

(A monthly roundup of the best of international publishing)