Europe Reimagined

AMONG THE many squibs fired at conventional wisdom by the historian AJP Taylor is an intriguing assertion about the relationship between history and contemporary affairs. 'The present enables us to understand the past,' Taylor maintained, 'not the other way round.' Now, most historians believe that the careful study of the past is essential to shed light on the present. Taylor not only denied this, but underscored the fact that our view of the past is unavoidably shaped by current concerns. The Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce said as much when he claimed that all history is contemporary history. A corollary to this is that moments of crisis are usually a spur to historical re-imagination. Indeed, we owe some of the best historical works of the 20th century to this impulse.

No part of the world is currently as shot through with a sense of crisis as Europe. This stems from multiple sources: the prolonged Eurozone economic crisis that also threatens to transform European politics; the return of great power tension following the Russian intervention in Ukraine; the continuing flow of refugees fleeing the war-torn Middle East; the return of terrorism under the Islamic State's banner. The grand European project, which has been underway since the early 1990s and which suggested that the continent had finally rid itself of the incubus of its previous century looks decidedly shaky. As if on cue, we have three large books on Europe's 20th century by leading historians.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

Ian Kershaw is perhaps best known as the author of a monumental two-volume biography of Hitler. To Hell and Back is his take on Europe in the period bookended by the two world wars. (A second volume dealing with the remainder of the century is in the works.) Heinrich August Winkler is arguably the leading public historian in Germany today; though only two of his books have so far been translated into English. In The Age of Catastrophe, Winkler covers the same period as Kershaw. The book, however, is the second in a series of four volumes that span the history of the West from classical antiquity to the present. Konrad Jarausch is a doyen of American historians of Germany and his Out of the Ashes is the most ambitious of this clutch of books. Not only does he take in the entire 20th century in a single volume, but he attempts an ambitious synthesis of political and economic, military and international, social and cultural history. Winkler, by contrast, provides a massively detailed political narrative of Europe's downward spiral into crises and wars. Kershaw, too, is primarily focused on war and international politics. He is also somewhat old-fashioned in garnishing a narrative driven by high politics with analyses of 'economic and social trends'.

These differences in approach and emphasis are accompanied by distinct ideological and intellectual orientations. Jarausch is a liberal Euro-Atlanticist, alert to differences between the old world and the new but also sympathetic to the European project. Kershaw almost epitomises the British empiricist idiom in the writing of history, adopting an Olympian tone that manages to mask his political leanings. Winkler's undertaking is the most explicitly ideological of the three. Subtitled 'A History of the West', it seeks to capture the evolutionary arc of the 'normative project of the West'— by which he refers to the legacy of the American and French Revolutions, or the ideas of political sovereignty and democracy. Winkler's larger project aims not only at showing how these ideas triumphed in the longer run but also at placing Germany's national history securely within this reading of the West.

Such differences apart, the three books share important features as well. For one thing, they are strongly German-centric accounts with France, Britain and Russia/Soviet Union as the other lead actors. For another, although they are aimed at a wide readership, none of these books resorts to the now popular gimmick of shaping the narrative around a few personalities ('How Hitler, Stalin, Churchill and De Gaulle Changed the World'). These are deeply researched, soberly argued and yet eminently accessible histories.

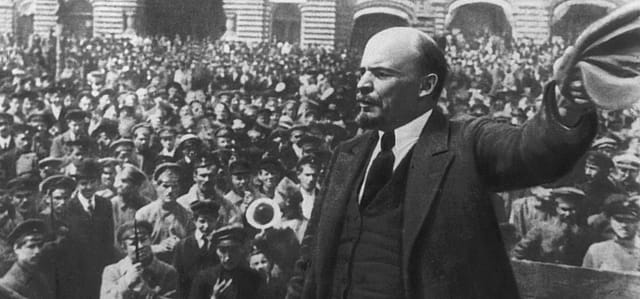

So, what's new in their reading of Europe's 20th century? The broad trajectory is, after all, well known. Starting with the unbounded confidence of the liberal European civilisation in 1900 marked by the World Fair in Paris to the carnage of World War I, the Russian revolution and the flawed Treaty of Versailles; the brief post-war recovery sliding into the Great Depression and collapse of liberal democratic governments; the challenge of the Fascist and Nazi states leading to the calamity of another global conflict accompanied by the Holocaust; the onset of the Cold War accompanied by three decades of post-war prosperity and the beginnings of economic integration in Western Europe; the economic crisis of the 1970s resulting in the ascendancy of neoliberalism and the onset of globalisation; the peaceful Eastern European revolutions of 1989 and the subsequent implosion of the Soviet Union; the reunification of Germany and the move towards 'ever closer union' in Europe. In historiographical terms, too, our interpretation of 20th century Europe is strongly shaped by two powerful books that were published two decades ago. Eric Hobsbawm's The Age of Extremes—written as the Soviet Union collapsed—presented a vision of the 'short twentieth century' spanning 1914 to 1989. The book accorded a central place to the Bolshevik revolution and argued that the collaboration between liberal democracy and communism to defeat fascism was the hinge on which the history of the century turned. Mark Mazower's Dark Continent was composed during the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s and emphasised how close Europe had come to being under the sway of the Nazi New Order. Ironically, it was the close brush with Nazism that gave liberal democracy a second lease of life in the continent.

Winkler's mammoth narrative responds to a still older vision of European history in the first half of the century: as that of a second Thirty Years' War, rather like the war between Catholic and Protestant states in the first half of the 17th century. This was the view espoused by contemporary actors such as De Gaulle and Churchill. It finds historiographical expression in the works of such distinguished— if ideologically and politically different—historians as Arno Mayer and Michael Howard. The comparison, Winkler observes, is illuminating in many ways. Like the Thirty Years' War, the two World Wars were fought not just

between states but also as an ideological battle that ran through them and even assumed the form of a civil war. Both these periods of war ended with settlements that divided Germany and the continent on the principle that the victor/ occupier could impose his own political order.

Yet, Winkler rightly holds, that thinking of the two World Wars as comprising another Thirty Years' War imparts a misleading fixity and inevitability to the first half of Europe's 20th century. The peace that had been produced by the Treaty of Versailles could have 'lasted much longer if the Weimar Republic had not been fatally buffeted by the storms of the world economic crisis and if it had not been replaced by Hitler's Führer state.' Indeed, the centrepiece of the book is his account of the collapse of the Weimar Republic when the democratic centre failed to mediate between the extreme Left and Right. His treatment of this episode is marred by a certain tendentiousness—especially in his reading of the inability of the Social Democrats to hold their party together while trying to form coalitions with the Liberals and Christian Democrats. In any event, he argues, the evisceration of democracy in Germany set the stage for the wider European collapse and descent into barbarism. Beyond this, however, Winkler advances no major argument—settling instead for 900 pages of magisterial narrative.

Kershaw, for his part, argues that there were four, interlocked elements of comprehensive crisis unique to these decades: an explosion of ethnic-racist nationalism; bitter and irreconcilable demands for territorial revisionism; intense class conflict given acute focus by the Bolshevik revolution in Russia; a protracted crisis of capitalism. Interestingly, he concedes that these were not causes of World War I but consequences of it. Nevertheless, he argues that the interaction of these elements help explain Europe's 'era of self-destruction'. Kershaw's judicious and balanced narrative traces the dynamic of escalation that resulted from the admixture of these factors. In particular, his synoptic treatment of World War II and the Holocaust is masterly.

Yet it seems fair to say that Kershaw is on stronger ground in analysing international politics than in explaining the jagged rhythms of the world economy. I also wonder about the novelty of his argument. In The War of the Worlds, Niall Ferguson had argued that the extreme violence of the 20th century was best explained by the conjunction of ethnic conflict, economic volatility and the decline of empires. While not unproblematic, this argument has the advantage of taking in the century as a whole and regions beyond Europe as well. Kershaw's plan for the two volumes also seems rather conventional. The second volume, he writes, will tell the story of how a new Europe emerged from 'the ashes of the old' and embarked on 'the road back from hell.'

The striking similarity of the imagery deployed by Kershaw and Jarausch should alert us to the fact that there is much in common in their accounts. Indeed, Jarausch's narrative of the first half of the century closely tracks that of Kershaw. This is perhaps inevitable in attempting such ambitious syntheses. Both authors draw on the best new writing on various aspects of the stories they tell, but they only selectively dip into the specialist literature and rely considerably on other surveys. This is especially true of their treatment of the Soviet Union. Jarausch, however, departs from Kershaw in the overarching vision that he offers. In his reading, Europe's 20th century was the story of a quest for modernity, but also a contest between competing versions of modernity: liberal democratic, communist and fascist; and then Americanisation and Sovietisation. By framing the story as one of competing modernities, Jarausch manages to do more than just sail with current academic fashion. It enables him to synthesise various aspects of Europe's experience across the century: economic crises and development, ideological competition between and within states, technological advance and warfare, developments in arts and sciences. It also allows him to underscore what was common to these multiple projects of modernity as well as what set them apart. This is also a useful corrective to the version of the history of the 'West' purveyed by Winkler.

Jarausch's book really comes into its own when dealing with the second half of the century. Here, he wonderfully pulls together various strands of the story of European integration and decolonisation, Cold War and the creation of the welfare state, deindustrialisation and globalisation. His sympathies are clearly with the social democratic project undertaken after World War II. But unlike, say, Tony Judt, he does not idealise it. He is, however, surprisingly soft on the European Union project—brushing aside criticism of a democratic deficit and overlooking the problems of conflating the EU with the Euro. He goes so far as to claim that Europe 'has been developing its own distinctive model of democratic and social modernity.' While the contrast with the US is unmistakable, Jarausch is clearly stretching the idea of competing modernities to a cracking point. This conception of alternative modernities (the EU and the US) is not really structural—about different social systems—but cultural, about morality and sensibility. This is very different from the competing visions of liberal, communist and fascist modernities.

The other shortcomings of Jarausch's work are those that it shares with the books by Winkler and Kershaw. To begin with, they are concerned primarily with the core European countries and hardly come to grips with its periphery. As Dominic Lieven has recently reminded us, there was a noticeable divide at the turn of the century between a First World Europe consisting of countries like Germany, France and Britain, and a Second World Europe including countries as diverse as Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Hungary and Russia. In this Second World periphery of Europe, the state was weaker, countries' regions less integrated, middle-classes smaller and property order less secure. This European periphery scarcely registers in these books. In a narrative of 800 pages, Jarausch barely mentions the Spanish civil war although it was a prominent theatre for the ideological rivalry that frames his story.

Further, the world beyond Europe does not play much of a causal role in these accounts either. The fact that the major European states were also empires is critical to understanding many aspects of the 20th century. Yet, except for a brief mention before World War I and, in Jarausch's case, during decolonisation, Europe's colonial history apparently had no impact on metropolitan politics. Is it really possible to explain a central theme of these books—the escalation of violence in Europe—without recognising the nature of the imperial projects in which these were engaged from the late 19th century onwards? Similarly, the US is absent for much of the first half of the century in these accounts. Yet, the 'shock of America' in politics, economics and culture was being felt in Europe from the early 1920s onwards.

By placing European history in a wider global context, these books might have given us a new interpretation rather than recycling the well-worn trope of catastrophe and regeneration. Jarausch captures the historical common sense in Europe about its recent past, when he writes that 'The bloody course of the twentieth century taught the Europeans a chastened outlook on modernity—a lesson some overconfident Americans have yet to learn.' This may well be true, but it is not clear that such a verdict will survive the current European crisis.